https://social.ayjay.org/2022/09/27/the-workshop.html

Walter Benjamin termed the book ‘an outdated mediationbetween two filing systems’

reference for this quote? date?

Walter Benjamin's fantastic re-definition of a book presaged the invention of the internet, though his instantiation was as a paper based machine.

Posted byu/lsumnler1 year agoHow is a commonplace book different than a zettelkasten? .t3_pguxq7._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } I get that physically the commonplace book is in a notebook whether physical or digitized and zettelkasten is in index cards whether physical or digitized but don't they server the same purpose.

Broadly the zettelkasten tradition grew out of commonplacing in the 1500s, in part, because it was easier to arrange and re-arrange one's thoughts on cards for potential reuse in outlining and writing. Most zettelkasten are just index card-based forms of commonplaces, though some following Niklas Luhmann's model have a higher level of internal links, connections, and structure.

I wrote a bit about some of these traditions (especially online ones) a while back at: https://boffosocko.com/2021/07/03/differentiating-online-variations-of-the-commonplace-book-digital-gardens-wikis-zettlekasten-waste-books-florilegia-and-second-brains/

Autor przedstawia ideę commonplace book, przywołując zbiór cytatów na ten temat, przedstawiając to, jak rozumiano ten sposób gromadzenia informacji i tekstów (miejsce do przechowywania wiedzy), jak robili to różni ludzie (notatniki z wydzielonymi działami); przedstawia też powody czy motywacje, stojące za taką praktyką (potrzeba przywołania myśli, zebranych argumentów), na końcu zestawia commonplace book z internetem.

Autorka przedstawia zagadnienie robienia notatek i ich organizacji. Podaje również techniczne informacje na temat notatników i sposobów zapisywania informacji.

Autorka przedstawia następujące metody notowania: - metoda Cornella - plan punktowy, zarys (outline) - mapa myśli - commonplace book (autorka pokazuje przykład notatek Leonarda da Vinci) - dziennik (bullet journal) - Zettelkasten.

Ponadto autorka jeszcze podaje wskazówki, dotyczące ulepszenia metod notowania: ręczne notowanie, wyodrębnianie najważniejszych zagadnień, zadawanie pytań, używanie własnych słów, tagowanie notatek.

Krótka historia nie tylko samej metody commonplace-book, co także informacje na temat książki Johna Locka (zob. Locke et al. 1706; Locke 1812) oraz dodatkowe informacje, zaczerpnięte z Roberta Darntona (Darnton 2000; zob. też: Darnton 2009). Na końcu są też informacje na temat porównania tej metody i prowadzenia notatek oraz strony przez samego autora, czyli Jeremy'ego Normana.

(Darnton, “Extraordinary Commonplaces,” New York Review of Books 47 (20)[December 21, 2000] 82, 86)

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2000/12/21/extraordinary-commonplaces/

Zob. też: Darnton 2009. (rozdział 10: The Mysteries of Reading)

Students' annotations canprompt first draft thinking, avoiding a blank page when writing andreassuring students that they have captured the critical informationabout the main argument from the reading.

While annotations may prove "first draft thinking", why couldn't they provide the actual thinking and direct writing which moves toward the final product? This is the sort of approach seen in historical commonplace book methods, zettelkasten methods, and certainly in Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten incarnation as delineated by Johannes Schmidt or variations described by Sönke Ahrens (2017) or Dan Allosso (2022)? Other similar variations can be seen in the work of Umberto Eco (MIT, 2015) and Gerald Weinberg (Dorset House, 2005).

Also potentially useful background here: Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. Yale University Press, 2010. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know

level 1mambocab · 2 days agoWhat a refreshing question! So many people (understandably, but annoyingly) think that a ZK is only for those kinds of notes.I manage my slip-box as markdown files in Obsidian. I organize my notes into folders named durable, and commonplace. My durable folder contains my ZK-like repository. commonplace is whatever else it'd be helpful to write. If helpful/interesting/atomic observations come out of writing in commonplace, then I extract them into durable.It's not a super-firm division; it's just a rough guide.

Other than my own practice, this may be the first place I've seen someone mentioning that they maintain dual practices of both commonplacing and zettelkasten simultaneously.

I do want to look more closely at Niklas Luhmann's ZKI and ZKII practices. I suspect that ZKI was a hybrid practice of the two and the second was more refined.

Andy 10:31AM Flag Thanks for sharing all this. In a Twitter response, @taurusnoises said: "we are all participating in an evolving dynamic history of zettelkasten methods (plural)". I imagine the plurality of methods is even more diverse than indicated by @chrisaldrich, who seems to be keen to trace everything through a single historical tradition back to commonplace books. But if you consider that every scholar who ever worked must have had some kind of note-taking method, and that many of them probably used paper slips or cards, and that they may have invented methods relatively independently and tailored those methods to diverse needs, then we are looking at a much more interesting plurality of methods indeed.

Andy, I take that much broader view you're describing. I definitely wouldn't say I'm keen to trace things through one (or even more) historical traditions, and to be sure there have been very many. I'm curious about a broad variety of traditions and variations on them; giving broad categorization to them can be helpful. I study both the written instructions through time, but also look at specific examples people have left behind of how they actually practiced those instructions. The vast majority of people are not likely to invent and evolve a practice alone, but are more likely likely to imitate the broad instructions read from a manual or taught by teachers and then pick and choose what they feel works for them and their particular needs. It's ultimately here that general laziness is likely to fall down to a least common denominator.

Between the 8th and 13th Centuries florilegium flouished, likely passed from user to user through a religious network, primarily facilitated by the Catholic Church and mendicant orders of the time period. In the late 1400s to 1500s, there were incredibly popular handbooks outlining the commonplace book by Erasmus, Agricola, and Melancthon that influenced generations of both teachers and students to come. These traditions ebbed and flowed over time and bent to the technologies of their times (index cards, card catalogs, carbon copy paper, computers, internet, desktop/mobile/browser applications, and others.) Naturally now we see a new crop of writers and "influencers" like Kuehn, Ahrens, Allosso, Holiday, Forte, Milo, and even zettelkasten.de prescribing methods which are variously followed (or not), understood, misunderstood, modified, and changed by readers looking for something they can easily follow, maintain, and which hopefully has both short term and long term value to them.

Everyone is taking what they want from what they read on these techniques, but often they're not presented with the broadest array of methods or told what the benefits and affordances of each of the methods may be. Most manuals on these topics are pretty prescriptive and few offer or suggest flexibility. If you read Tiago Forte but don't need a system for work or project-based productivity but rather need a more Luhmann-like system for academic writing, you'll have missed something or will only have a tool that gets you part of what you may have needed. Similarly if you don't need the affordances of a Luhmannesque system, but you've only read Ahrens, you might not find the value of simplified but similar systems and may get lost in terminology you don't understand or may not use. The worst sin, in my opinion, is when these writers offer their advice, based only on their own experiences which are contingent on their own work processes, and say this is "the way" or I've developed "this method" over the past decade of grueling, hard-fought experience and it's the "secret" to the "magic of note taking". These ideas have a long and deep history with lots of exploration and (usually very little) innovation, but an average person isn't able to take advantage of this because they're only seeing a tiny slice of these broader practices. They're being given a hammer instead of a whole toolbox of useful tools from which they might choose. Almost none are asking the user "What is the problem you're trying to solve?" and then making suggestions about what may or may not have worked for similar problems in the past as a means of arriving at a solution. More often they're being thrown in the deep end and covered in four letter acronyms, jargon, and theory which ultimately have no value to them. In other cases they're being sold on the magic of productivity and creativity while the work involved is downplayed and they don't get far enough into the work to see any of the promised productivity and creativity.

Each slip ought to be furnished with precise refer-ences to the source from which its contents havebeen derived ; consequently, if a document has beenanalysed upon fifty different slips, the same refer-ences must be repeated fifty times. Hence a slightincrease in the amount of writing to be done. Itis certainly on account of this trivial complicationthat some obstinately cling to the inferior notebooksystem.

A zettelkasten may require more duplication of effort than a notebook based system in terms of copying.

It's likely that the attempt to be lazy about copying was what encouraged Luhmann to use his particular system the way he did.

Every one admits nowadays that it is advisable tocollect materials on separate cards or slips of paper.

A zettelkasten or slip box approach was commonplace, at least by historians, (excuse the pun) by 1898.

Given the context as mentioned in the opening that this books is for a broader public audience, the idea that this sort of method extends beyond just historians and even the humanities is very likely.

tions will not always fit without inconvenience intotheir proper place ; and the scheme of classification,once adopted, is rigid, and can only be modifiedwith difficulty. Many librarians used to draw uptheir catalogues on this plan, which is now uni-versally condemned.

Others, well understanding the advantages of systematic classification, have proposed to fit their materials, as fast as collected, into their appropriate places in a prearranged scheme. For this purpose they use notebooks of which every page has first been provided with a heading. Thus all the entries of the same kind are close to one another. This system leaves something to be desired; for addi

The use of a commonplace method for historical research is marked as a poor choice because:<br /> The topics with similar headings may be close together, but ideas may not ultimately fit into their pre-allotted spaces.<br /> The classification system may be too rigid as ideas change and get modified over time.

They mention that librarians used to catalog books in this method, but that they realized that their system would be out of date almost immediately. (I've got some notes on this particular idea to which this could be directly linked as evidence.)

Der Gelehrte griff bei der Wissensproduktion nur noch auf den flüchtigen Speicher der Exzerptsammlungen zurück, die die loci communes enthielten: die "Gemeinplätze", die wir auch heute sprichwörtlich noch so nennen. Gesner nannte diese Sammlungen "chartaceos libros", also Karteibücher. Er erfand ein eigenes Verfahren, mit dem die einzelnen Notate jederzeit derangierbar und damit auch neu arrangierbar waren, um der Informationsflut Rechnung zu tragen und ständig neue Einträge hinzugefügen zu können. "Du weißt, wie leicht es ist, Fakten zu sammeln, und wie schwer, sie zu ordnen", schrieb der Basler Gelehrte Caspar Wolf, der Herausgeber der Werke Gesners.

For the production of knowledge, the scholar only resorted to the volatile memory of the excerpt collections, the [[loci communes]] contained: the "platitudes" that we still literally call that today. Gesner called these collections "chartaceos libros", that is, index books. He invented his own method with which the individual notes could be rearranged at any time and thus rearranged in order to take account of the flood of information and to be able to constantly add new entries. "You know how easy it is to collect facts and how difficult it is to organize them," wrote the Basel scholar [[Caspar Wolf]], editor of Gesner's works.

Is this translation of platitudes correct/appropriate here? Maybe aphorisms or the Latin sententiae (written wisdom) are better?

I'd like to look more closely at his method. Was he, like Jean Paul, using slips of paper which he could move around within a particular book? Perhaps the way one might move photos around in a photo album with tape/adhesive?

war der Schweizer Humanist Conrad Gesner. Gesners Bibliotheca Universalis, die zwischen 1545 und 1548 in zwei Foliobänden mit jeweils über 1000 Seiten erschien, sollte alle Bücher verzeichnen, die seit Gutenberg erschienen waren.

Swiss humanist Conrad Gesner. Gesner's Bibliotheca Universalis, which appeared between 1545 and 1548 in two folio volumes with over 1000 pages each, was supposed to list all the books that had appeared since Gutenberg.

In Bibliotheca Universalis, Conrad Gesner collected a list that was supposed to list all the books which had appeared since Gutenberg's moveable type.

als deren Meister sich sein Zeitgenosse Johann Jacob Moser (1701-1785) erwies. Die Verzettelungstechnik des schwäbischen Juristen und Schriftstellers ist ein nachdrücklicher Beleg dafür, wie man allein durch Umadressierung aus den Exzerpten alter Bücher neue machen kann. Seine auf über 500 Titel veranschlagte Publikationsliste hätte Moser nach eigenem Bekunden ohne das von ihm geschaffene Hilfsmittel nicht bewerkstelligen können. Moser war auch einer der ersten Theoretiker des Zettelkastens. Unter der Überschrift "Meine Art, Materialien zu künfftigen Schrifften zu sammlen" hat er selbst die Algorithmen beschrieben, mit deren Hilfe er seine "Zettelkästgen" füllte.

the master of which his contemporary Johann Jacob Moser (1701-1785) proved to be. The technique used by the Swabian lawyer and writer to scramble is emphatic evidence of how you can turn excerpts from old books into new ones just by re-addressing them. According to his own admission, Moser would not have been able to manage his publication list, which is estimated at over 500 titles, without the aid he had created. Moser was also one of the first theorists of the card box. Under the heading "My way of collecting materials for future writings", he himself described the algorithms with which he filled his "card boxes".

Johann Jacob Moser was a commonplace book keeper who referenced his system as a means of inventio. He wrote about how he collected material for future writing and described the ways in which he filled his "card boxes".

I'm curious what his exact method was and if it could be called an early precursor of the zettelkasten?

For the sheets that are filled with content on one side however, the most most importantaspect is its actual “address”, which at the same time gives it its title by which it can alwaysbe found among its comrades: the keyword belongs to the upper row of the sheet

following the commonplace tradition, the keyword gets pride of place...

Watch here the word "address" and double check the original German word in translation. What was it originally? Seems a tad odd to hear "address" applied to a keyword which is likely to be just one of many. How to keep them all straight?

scientists as well asstudents of science carefully put the diverse results of their reading and thinking process intoone or a few note books that are separated by topic.

A specific reference to the commonplace book tradition and in particular the practice of segmenting note books into pre-defined segments with particular topic headings. This practice described here also ignores the practice of keeping an index (either in a separate notebook or in the front/back of the notebook as was more common after John Locke's treatise)

level 2hog8541ssOp · 15 hr. agoVery nice! I am a pastor so I am researching Antinet being used along with Bible studies.

If you've not come across the examples, one of the precursors of the slip box tradition was the widespread use of florilegia from the 8th through the 13th centuries and beyond, and they were primarily used for religious study, preaching, and sermon writing.

A major example of early use was by Philip Melanchthon, who wrote a very popular handbook on how to keep a commonplace. He's one of the reasons why many Lutheran books are called or have Commonplace in the title.

A fantastic example is that of American preacher Jonathan Edwards which he called by an alternate name of Miscellanies which is now digitized and online, much the way Luhmann's is: http://edwards.yale.edu/research/misc-index Apparently he used to pin slips with notes on his coat jacket!

If I recall, u/TomKluender may have some practical experience in the overlap of theology and zettelkasten.

(Moved this comment to https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/wth5t8/bible_study_and_zettelkasten/ as a better location for the conversation)

https://howaboutthis.substack.com/p/the-knowledge-that-wont-fit-inside

Reasonable overview article with some nice pros/cons.

On the Internet there are many collective projects where users interact only by modifying local parts of their shared virtual environment. Wikipedia is an example of this.[17][18] The massive structure of information available in a wiki,[19] or an open source software project such as the FreeBSD kernel[19] could be compared to a termite nest; one initial user leaves a seed of an idea (a mudball) which attracts other users who then build upon and modify this initial concept, eventually constructing an elaborate structure of connected thoughts.[20][21]

Just as eusocial creatures like termites create pheromone infused mudballs which evolve into pillars, arches, chambers, etc., a single individual can maintain a collection of notes (a commonplace book, a zettelkasten) which contains memetic seeds of ideas (highly interesting to at least themselves). Working with this collection over time and continuing to add to it, modify it, link to it, and expand it will create a complex living community of thoughts and ideas.

Over time this complexity involves to create new ideas, new structures, new insights.

Allowing this pattern to move from a single person and note collection to multiple people and multiple collections will tend to compound this effect and accelerate it, particularly with digital tools and modern high speed communication methods.

(Naturally the key is to prevent outside selfish interests from co-opting this behavior, eg. corporate social media.)

The network of trails functions as a shared external memory for the ant colony.

Just as a trail of pheromones serves the function of a shared external memory for an ant colony, annotations can create a set of associative trails which serve as an external memory for a broader human collective memory. Further songlines and other orality based memory methods form a shared, but individually stored internal collective memory for those who use and practice them.

Vestiges of this human practice can be seen in modern society with the use and spread of cultural memes. People are incredibly good at seeing and recognizing memes and what they communicate and spreading them because they've evolved to function this way since the dawn of humanity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gT1EExZkzMM

Quick outline of how Holiday reads, annotates, and then processes the ideas from books into his index card-based commonplace book.

https://thoughtcatalog.com/ryan-holiday/2013/08/how-and-why-to-keep-a-commonplace-book/

An early essay from Ryan Holiday about commonplace books including how, why, and their general value.

Notice that the essay almost reads as if he's copying out cards from his own system. This is highlighted by the fact that he adds dashes in front 23 of his paragraphs/points.

Protect it at all costs. As the historian Douglas Brinkley said about Ronald Reagan’s collection of notecards: “If the Reagans’ home in Palisades were burning, this would be one of the things Reagan would immediately drag out of the house. He carried them with him all over like a carpenter brings their tools. These were the tools for his trade.”

Another example of saving one's commonplace in case of a fire!

link to: - https://hypothes.is/a/BLL9TvZ9EeuSIrsiWKCB9w - https://hypothes.is/a/zHUghMiaEeuKKvcrc5ux5w

I’ve been keeping my commonplace books in variety of forms for 6 or 7 years. But I’m just getting started.

In August 2013 Ryan Holiday said that he'd been commonplacing for "6 or 7 years".

Don’t worry about organization…at least at first. I get a lot of emails from people asking me what categories I organize my notes in. Guess what? It doesn’t matter. The information I personally find is what dictates my categories. Your search will dictate your own. Focus on finding good stuff and the themes will reveal themselves.

Ryan Holiday's experience and advice indicates that he does little organization and doesn't put emphasis on categories for organization. He advises "Focus on finding good stuff and the themes will reveal themselves."

This puts him on a very particular part of the spectrum in terms of his practice.

Ronald Reagan actually kept quotes on a similar notecard system.

By at least 2013 Ryan Holiday was aware of Ronald Reagan's note card system from a 2011 USA Today article and related book.

I use 4×6 ruled index cards, which Robert Greene introduced me to. I write the information on the card, and the theme/category on the top right corner. As he figured out, being able to shuffle and move the cards into different groups is crucial to getting the most out of them.

Ryan Holiday keeps a commonplace book on 4x6 inch ruled index cards with a theme or category written in the top right corner. He learned his system from Robert Greene.

Of crucial importance to him was the ability to shuffle the cards and move them around.

A commonplace book is a way to keep our learning priorities in order. It motivates us to look for and keep only the things we can use.

And if you still need a why–I’ll let this quote from Seneca answer it (which I got from my own reading and notes): “We should hunt out the helpful pieces of teaching and the spirited and noble-minded sayings which are capable of immediate practical application–not far far-fetched or archaic expressions or extravagant metaphors and figures of speech–and learn them so well that words become works.”

https://thoughtcatalog.com/ryan-holiday/2013/08/how-and-why-to-keep-a-commonplace-book/

Holiday followed this article up two days later with https://thoughtcatalog.com/ryan-holiday/2013/08/everyone-should-keep-a-commonplace-book-great-tips-from-people-who-do/

This article predated a somewhat related LifeHacker piece: https://lifehacker.com/im-ryan-holiday-and-this-is-how-i-work-1485776137

https://lifehacker.com/im-ryan-holiday-and-this-is-how-i-work-1485776137

An influential productivity article from 2013-12-18 that is seen quoted over the blogosphere for the following years that broadened the idea of the commonplace book and the later popularity of the zettelkasten.

Note that zettelkasten.de was just starting up at about this time period, though it follows the work of Manfred Kuehn's note taking blog.

It's several thousand 4x6 notecards—based on a system taught to by my mentor Robert Greene when I was his research assistant—that have ideas, notes on books I liked, quotes that caught my attention, research for projects or phrases I am kicking around.

Ryan Holiday learned his index card-based commonplace book system from writer Robert Greene for whom he worked as an assistant.

My Commonplace Book (pictured above) is the first thing I'm taking out of my house in a fire.

As a strong indicator of how important his commonplace book is, Ryan Holiday not only indicates that it's the tool he can't live without but he says it "is the first thing I'm taking out of my house in a fire."

Link to: - https://hypothes.is/a/KCnrXMdHEeyxz3sZy3Uo5g

Cross reference with his fears of robbery as well: - https://hypothes.is/a/BLL9TvZ9EeuSIrsiWKCB9w

to networked commonplace books

Alright Jerry, you got me, I'm in!

He explains the purpose of his "waste book" in his notebook E: Die Kaufleute haben ihr Waste book (Sudelbuch, Klitterbuch glaube ich im deutschen), darin tragen sie von Tag zu Tag alles ein was sie verkaufen und kaufen, alles durch einander ohne Ordnung, aus diesem wird es in das Journal getragen, wo alles mehr systematisch steht ... Dieses verdient von den Gelehrten nachgeahmt zu werden. Erst ein Buch worin ich alles einschreibe, so wie ich es sehe oder wie es mir meine Gedancken eingeben, alsdann kann dieses wieder in ein anderes getragen werden, wo die Materien mehr abgesondert und geordnet sind.[2] "Tradesmen have their 'waste book' (scrawl-book, composition book I think in German), in which they enter from day to day everything they buy and sell, everything all mixed up without any order to it, from there it is transferred to the day-book, where everything appears in more systematic fashion ... This deserves to be imitated by scholars. First a book where I write down everything as I see it or as my thoughts put it before me, later this can be transcribed into another, where the materials are more distinguished and ordered."

Organization of both a commonplace book and pocket notebook .t3_w1vq6q._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; }

Historically, following a tradition from accounting ledgers, people kept small, convenient pocket notebooks called "waste books" for quickly capturing notes and ideas in daily life. Later, they'd either expand on them or copy them out in better detail and usually in a nicer hand with sources/citations, and indexing/cross referencing in their permanent commonplaces. When you're done with it, you'd simply dispose of or throw away the waste book.

As for arrangement or organization, it's been common for people to use something roughly similar to John Locke's indexing method from 1706 for arranging and finding material. Others use a card index file and index cards to be able to rearrange pieces or to more easily index and cross reference portions.

I often recommend https://indieweb.org/commonplace_book as a pretty solid resource with some history, books, articles, and lots of examples (both digital and analog/paper-based) one might look at to find what they think would be best for themselves.

Beatrice Webb, the famous sociologist and political activist, reported in 1926: "'Every one agrees nowadays', observe the most noted French writers on the study of history, 'that it is advisable to collect materials on separate cards or slips of paper. . . . The advantages of this artifice are obvious; the detachability of the slips enables us to group them at will in a host of different combinations; if necessary, to change their places; it is easy to bring texts of the same kind together, and to incorporate additions, as they are acquired, in the interior of the groups to which they belong.'" [6]

footnote:

Webb 1926, p. 363. The number of scholars who have used the index card method is legion, especially in sociology and anthropology, but also in many other subjects. Claude Lévy-Strauss learned their use from Marcel Mauss and others, Roland Barthes used them, Charles Sanders Peirce relied on them, and William Van Orman Quine wrote his lectures on them, etc.

https://medium.com/@paulorrj/the-robert-greene-method-of-writing-books-e175ade04897

meh...

Robert uses a system based on flashcards

flashcards?!?!! A commonplace book done in index cards is NOT based on "flashcards". 🤮

Someone here is missing the point...

In his interviews, he likes to emphasize that, in each book, he’s back to square one.

Where does Robert Greene specifically say this?

With a commonplace book repository, one is never really starting from square one. Anyone who says otherwise is missing the point.

with established worldwide fame and prestige, to step in his previous successes to write more-of-the-same books and convert all the attention in cheap money. Just like Robert Kiyosaki did with his 942357 books about “Rich dad”.

Many artists fall into a creativity trap caused by fame. They spend years developing a great work, but then when it's released, the industry requires they follow it up almost immediately with something even stronger.

Jewel is an reasonable and perhaps typical example of this phenomenon. She spent several years writing the entirety of her first album Pieces of You (1995), which had three to four solid singles. As it became popular she was rushed to release Spirit (1998), which, while it was ultimately successful, didn't measure up to the first album which had far more incubation time. She wasn't able to build up enough material over time to more easily ride her initial wave of fame. Creativity on demand can be a difficult master, particularly when one is actively touring or supporting their first work while needing to

(Compare the number of titles she self-wrote on album one vs. album two).

M. Night Shyamalan is in a similar space, though as a director he preferred to direct scripts that he himself had written. While he'd had several years of writing and many scripts, some were owned by other production companies/studios which forced him to start from scratch several times and both write and direct at the same time, a process which is difficult to do by oneself.

Another example is Robert Kiyosaki who spun off several similar "Rich Dad" books after the success of his first.

Compare this with artists who have a note taking or commonplacing practice for maintaining the velocity of their creative output: - Eminem - stacking ammo - Taylor Swift - commonplace practice

Realizing that my prior separate advice wasn't as actionable or specific, I thought I'd take another crack at your question.

Some seem to miss the older techniques and names for this sort of practice and get too wound up in words like categories, tags, #hashtags, [[wikilinks]], or other related taxonomies and ontologies. Some become confounded about how to implement these into digital systems. Simplify things and index your ideas/notes the way one would have indexed books in a library card catalog, generally using subject, author and title.

Since you're using an approach more grounded in the commonplace book tradition rather than a zettelkasten one, put an easy identifier on your note (this can be a unique title or number) and then cross reference it with any related subject headings or topical category words you find useful.

Here's a concrete example, hopefully in reasonable detail that one can easily follow. Let's say you have a quote you want to save:

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them.—Umberto Eco, Foucault's Pendulum

In a paper system you might give this card the identification number #237. (This is analogous to the Dewey Decimal number that might be put on a book to find it on the shelves.) You want to be able to find this quote in the future using the topical words "power", "information", "connections", and "quotes" for example. (Which topical headings you choose and why can be up to you, the goal is to make it easier to dig up for potential reuse in future contexts). So create a separate paper index with alphabetical headings (A-Z) and then write cards for your topical headings. Your card with "power" at the top will have the number #237 on it to indicate that that card is related to the word power. You'll ultimately have other cards that relate and can easily find everything related to "power" within your system by using this subject index.

You might also want to file that quote under two other "topics" which will make it easy to find: primarily the author of the quote "Umberto Eco" and the title of the source Foucault's Pendulum. You can add these to your index the same way you did "power", "information", etc., but it may be easier or more logical to keep a bibliographic index separately for footnoting your material, so you might want a separate bibliographic index for authors and sources. If you do this, then create a card with Umberto Eco at the top and then put the number #237 on it. Later you'll add other numbers for other related ideas to Eco. You can then keep your card "Eco, Umberto" alphabetized with all the other authors you cite. You'll effect a similar process with the title.

With this done, you now have a system in which you don't have to categorize a single idea in a single place. Regardless of what project or thing you're working on, you can find lots of related notes. If you're juggling multiple projects you can have an index file or document outline for these as well. So your book project on the History of Information could have a rough outline of the book on which you've got the number #237 in the chapter or place where you might use the quote.

Hopefully this will be even more flexible than Holiday's system because that was broadly project based. In practice, if you're keeping notes over a lifetime, you're unlikely to be interested in dramatically different areas the way Ryan Holiday or Robert Greene were for disparate book projects, but will find more overlapping areas. Having a more flexible system that will allow you to reuse your notes for multiple settings or projects will be highly valuable.

For those who are using digital systems, ask yourself: "what functions and features allow you to do these analog patterns most easily?" If you're using something like Obsidian which has #tagging functionality that automatically creates an index of all your tags, then leverage that and remove some of the manual process. The goal is to make sure the digital system is creating the structure to allow you to easily find and use your notes when you need them. If your note taking system doesn't have custom functionalities for any of these things, then you'll need to do more portions of them manually.

Looking for advice on how to adapt antinet ideas for my own system .t3_vkllv0._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; }

Holiday's system is roughly similar to the idea of a commonplace book, just kept and maintained on index cards instead of a notebook. He also seems to advocate for keeping separate boxes for each project which I find to be odd advice, though it's also roughly the same advice suggested by Twyla Tharp's The Creative Habit and Tiago Forte's recent book Building a Second Brain which provides a framing that seems geared more toward broader productivity rather than either the commonplacing or zettelkasten traditions.

I suspect that if you're not linking discrete ideas, you'll get far more value out of your system by practicing profligate indexing terms on your discrete ideas. Two topical/subject headings on an individual idea seems horrifically limiting much less on an entire article and even worse on a whole book. Fewer index topics is easier to get away with in a digital system which allows search across your corpus, but can be painfully limiting in a pen/paper system.

Most paperbound commonplaces index topics against page numbers, but it's not clear to me how you're numbering (or not) your system to be able to more easily cross reference your notes with an index. Looking at Luhmann's index as an example (https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_SW1_001_V) might be illustrative so you can follow along, but if you're not using his numbering system or linking your cards/ideas, then you could simply use consecutive numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, ..., 92000, 92001, ... on your cards to index against to easily find the cards you're after. It almost sounds to me that with your current filing system, you'd have to duplicate your cards to be able to file them under more than one topic. This obviously isn't ideal.

If you’d like to give this approach to executing projects a try, now isthe perfect time.Start by picking one project you want to move forward on. It couldbe one you identified in Chapter 5, when I asked you to make foldersfor each active project.

At least two examples of the book attempting to engage the reader in carrying out the principles within.

I wonder how many tried?

You never knowwhen the rejected scraps from one project might become the perfectmissing piece in another. The possibilities are endless.

He says this, but his advice on how to use them is too scant and/or flawed. Where are they held? How are they indexed? How are they linked so that finding and using them in the future? (especially, other than rote memory or the need to have vague memory and the ability to search for them in the future?)

• Write down ideas for next steps: At the end of a worksession, write down what you think the next steps could be forthe next one.• Write down the current status: This could include your currentbiggest challenge, most important open question, or futureroadblocks you expect.• Write down any details you have in mind that are likely tobe forgotten once you step away: Such as details about thecharacters in your story, the pitfalls of the event you’re planning,or the subtle considerations of the product you’re designing.• Write out your intention for the next work session: Set anintention for what you plan on tackling next, the problem youintend to solve, or a certain milestone you want to reach.

A lot of this is geared toward the work of re-contextualizing one's work and projects.

Why do all this extra work instead of frontloading it? Here again is an example of more work in comparison to zettelkasten...

The Archipelago of Ideas

This idea doesn't appear in Steven Johnson's book itself, but only in this quirky little BoingBoing piece, so I'll give Forte credit for using his reading and notes from this piece to create a larger thesis here.

I'm not really a fan of this broader archipelago of ideas as it puts the work much later in the process. For those not doing it upfront by linking ideas as they go, it's the only reasonable strategy left for leveraging one's notes.

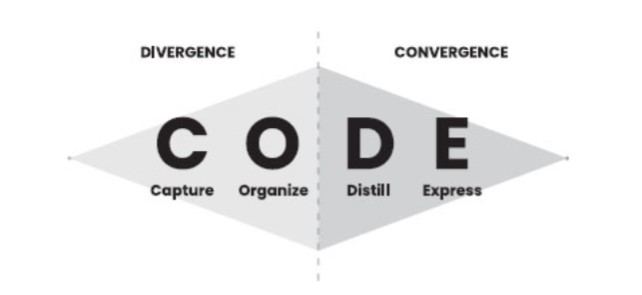

If we overlay the four steps of CODE onto the model ofdivergence and convergence, we arrive at a powerful template forthe creative process in our time.

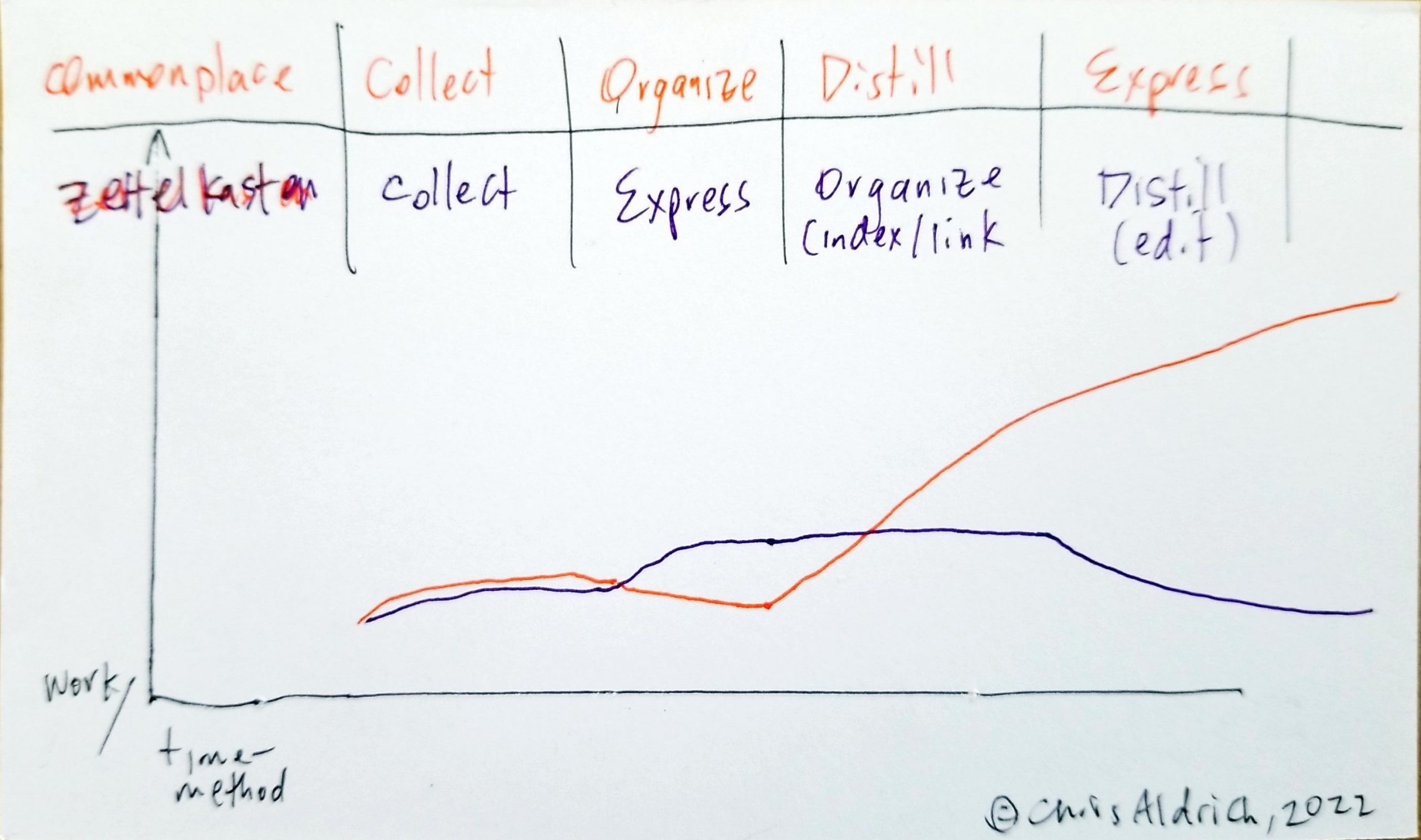

The way that Tiago Forte overlaps the idea of C.O.D.E. (capture/collect, organize, distill, express) with the divergence/convergence model points out some primary differences of his system and that of some of the more refined methods of maintaining a zettelkasten.

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book Building a Second Brain (Atria Books, 2022) </small>

<small>Overlapping ideas of C.O.D.E. and divergence/convergence from Tiago Forte's book Building a Second Brain (Atria Books, 2022) </small>

Forte's focus on organizing is dedicated solely on to putting things into folders, which is a light touch way of indexing them. However it only indexes them on one axis—that of the folder into which they're being placed. This precludes them from being indexed on a variety of other axes from the start to other places where they might also be used in the future. His method requires more additional work and effort to revisit and re-arrange (move them into other folders) or index them later.

Most historical commonplacing and zettelkasten techniques place a heavier emphasis on indexing pieces as they're collected.

Commonplacing creates more work on the user between organizing and distilling because they're more dependent on their memory of the user or depending on the regular re-reading and revisiting of pieces one may have a memory of existence. Most commonplacing methods (particularly the older historic forms of collecting and excerpting sententiae) also doesn't focus or rely on one writing out their own ideas in larger form as one goes along, so generally here there is a larger amount of work at the expression stage.

Zettelkasten techniques as imagined by Luhmann and Ahrens smooth the process between organization and distillation by creating tacit links between ideas. This additional piece of the process makes distillation far easier because the linking work has been done along the way, so one only need edit out ideas that don't add to the overall argument or piece. All that remains is light editing.

Ahrens' instantiation of the method also focuses on writing out and summarizing other's ideas in one's own words for later convenient reuse. This idea is also seen in Bruce Ballenger's The Curious Researcher as a means of both sensemaking and reuse, though none of the organizational indexing or idea linking seem to be found there.

This also fits into the diamond shape that Forte provides as the height along the vertical can stand in as a proxy for the equivalent amount of work that is required during the overall process.

This shape could be reframed for a refined zettelkasten method as an indication of work

Forte's diamond shape provided gives a visual representation of the overall process of the divergence and convergence.

But what if we change that shape to indicate the amount of work that is required along the steps of the process?!

Here, we might expect the diamond to relatively accurately reflect the amounts of work along the path.

If this is the case, then what might the relative workload look like for a refined zettelkasten? First we'll need to move the express portion between capture and organize where it more naturally sits, at least in Ahren's instantiation of the method. While this does take a discrete small amount of work and time for the note taker, it pays off in the long run as one intends from the start to reuse this work. It also pays further dividends as it dramatically increases one's understanding of the material that is being collected, particularly when conjoined to the organization portion which actively links this knowledge into one's broader world view based on their notes. For the moment, we'll neglect the benefits of comparison of conjoined ideas which may reveal flaws in our thinking and reasoning or the benefits of new questions and ideas which may arise from this juxtaposition.

This sketch could be refined a bit, but overall it shows that frontloading the work has the effect of dramatically increasing the efficiency and productivity for a particular piece of work.

Note that when compounded over a lifetime's work, this diagram also neglects the productivity increase over being able to revisit old work and re-using it for multiple different types of work or projects where there is potential overlap, not to mention the combinatorial possibilities.

--

It could be useful to better and more carefully plot out the amounts of time, work/effort for these methods (based on practical experience) and then regraph the resulting power inputs against each other to come up with a better picture of the efficiency gains.

Is some of the reason that people are against zettelkasten methods that they don't see the immediate gains in return for the upfront work, and thus abandon the process? Is this a form of misinterpreted-effort hypothesis at work? It can also be compounded at not being able to see the compounding effects of the upfront work.

What does research indicate about how people are able to predict compounding effects over time in areas like money/finance? What might this indicate here? Humans definitely have issues seeing and reacting to probabilities in this same manner, so one might expect the same intellectual blindness based on system 1 vs. system 2.

Given that indexing things, especially digitally, requires so little work and effort upfront, it should be done at the time of collection.

I'll admit that it only took a moment to read this highlighted sentence and look at the related diagram, but the amount of material I was able to draw out of it by reframing it, thinking about it, having my own thoughts and ideas against it, and then innovating based upon it was incredibly fruitful in terms of better differentiating amongst a variety of note taking and sense making frameworks.

For me, this is a great example of what reading with a pen in hand, rephrasing, extending, and linking to other ideas can accomplish.

As powerful and necessary as divergence is, if all we ever do isdiverge, then we never arrive anywhere.

Tiago Forte frames the creative process in the framing of divergence (brainstorming) and convergence (connecting ideas, editing, refining) which emerged out of the Stanford Design School and popularized by IDEO in the 1980s and 1990s.

But this is just what the more refined practices of maintaining a zettelkasten entail. It's the creation of profligate divergence forced by promiscuously following one's interests and collecting ideas along the way interspersed with active and pointed connection of ideas slowly creating convergence of these ideas over time. The ultimate act of creation finally becomes simple as pulling one's favorite idea of many out of the box (along with all the things connected to it) and editing out any unnecessary pieces and then smoothing the whole into something cohesive.

This is far less taxing than sculpting marble where one needs to start with an idea of where one is going and then needs the actual skill to get there. Doing this well requires thousands of hours of practice at the skill, working with smaller models, and eventually (hopefully) arriving at art. It's much easier if one has the broad shapes of the entirety of Rodin, Michelangelo, and Donatello's works in their repository and they can simply pull out one that feels interesting and polish it up a bit. Some of the time necessary for work and practice are still there, but the ultimate results are closer to guaranteed art in one domain than the other.

Commonplacing or slipboxing allows us to take the ability to imitate, which humans are exceptionally good at (Annie Murphy Paul, link tk), and combine those imitations in a way to actively explore and then create new innovative ideas.

Commonplacing can be thought of as lifelong and consistent practice of brainstorming where one captures all the ideas for later use.

Link to - practice makes perfect

This standardized routine is known as the creative process, and itoperates according to timeless principles that can be foundthroughout history.

If the creative process has timeless principles found throughout history, why aren't they written down and practiced religiously withing our culture that is so enamored of creativity and innovation?

As an example of how this isn't true, we've managed to lose our commonplace tradition and haven't really replaced it with anything useful. Even the evolved practice of the zettelkasten has been created and generally discarded (pun intended) without replacement.

How much of our creative process is reliant on simple imitation, which is a basic human trait? It's typically more often that imitation juxtaposed with other experiences which is the crucible of innovation. How often, if ever, is true innovation in an entirely different domain created? By this I mean innovation outside of the adjacent possible domains from which it stems? Are there any examples of this?

Even my own note taking practice is a mélange of broad imitation of what I read combined with the combinatorial juxtaposition of other ideas in an attempt to create new ideas.

How to Resurface and Reuse Your Past Work

Coming back to the beginning of this section. He talks about tags, solely after-the-fact instead of when taking notes on the fly. While it might seem that he would have been using tags as subject headings in a traditional commonplace book, he really isn't. This is a significant departure from the historical method!! It's also ill advised not to be either tagging/categorizing as one goes along to make searching and linking things together dramatically easier.

How has he missed the power of this from the start?! This is really a massive flaw in his method from my perspective, particularly as he quotes John Locke's work on the topic.

Did I maybe miss some of this in earlier sections when he quoted John Locke? Double check, just in case, but this is certainly the section of the book to discuss using these ideas!

Over time, your ability to quickly tap these creative assets andcombine them into something new will make all the difference in yourcareer trajectory, business growth, and even quality of life

I'm curious how he's going to outline this practice as there's been no discussion of linking or cross-linking ideas prior to this point as is done in some instantiations of the zettelkasten methods. (Of course this interlinking is more valuable when it comes specifically to writing output; once can rely on subject headings and search otherwise.)

The idea of startinganything from scratch will become foreign to you—why not draw onthe wealth of assets you’ve invested in in the past?

He uses the idea of "wealth" here for notes created in a commonplace instead of "treasure" or storehouse as is the historical tradition, this is an indication of a complete schism between the older traditions and the new.

Thus began a lifelong relationship with her commonplace books.Butler would scrape together twenty-five cents to buy small Meadmemo pads, and in those pages she took notes on every aspect ofher life: grocery and clothes shopping lists, last-minute to-dos,wishes and intentions, and calculations of her remaining funds forrent, food, and utilities. She meticulously tracked her daily writinggoals and page counts, lists of her failings and desired personalqualities, her wishes and dreams for the future, and contracts she

would sign with herself each day for how many words she committed to write.

Not really enough evidence for a solid quote here. What was his source?

He cites the following shallowly: <br /> - Octavia E. Butler, Bloodchild and Other Stories: Positive Obsession (New York: Seven Stories, 2005), 123–36.<br /> - 2 Lynell George, A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler (Santa Monica: Angel City Press, 2020).<br /> - 3 Dan Sheehan, “Octavia Butler has finally made the New York Times Best Seller list,” LitHub.com, September 3, 2020, https://lithub.com/octavia- butler-has-finally-made-the-new-york-times-best-seller-list/.<br /> - 4 Butler’s archive has been available to researchers and scholars at the Huntington Library since 2010.

UsingPARA is not just about creating a bunch of folders to put things in. Itis about identifying the structure of your work and life—what you arecommitted to, what you want to change, and where you want to go.

Using the P.A.R.A. method puts incredible focus on immediate projects and productivity toward them. This is a dramatically different focus from the zettelkasten method.

The why's of the systems are dramatically different as well.

We are organizing for actionability

Organize for actionability.

(Applicable only for P.A.R.A.?)

This is interesting for general project management, but potentially not for zettelkasten-type notes. That method has more flexibility that doesn't require this sort of organizational method and actually excels as a result of it.

There is a tension here.

Notes primarily for project-based productivity are different from notes for writing-based output.

Archives: Things I’ve Completed or Put on Hold

The P.A.R.A. method seems like an admixture of one's projects/to do lists and productivity details and a more traditional commonplace book. Keeping these two somewhat separate mentally may help users with respect to how these folders should be used.

Resources: Things I Want to Reference in the Future

Resources (of P.A.R.A.) sound specifically like a more traditional commonplace book space.

Be regular and orderly in your life so that you may be violent andoriginal in your work.—Gustave Flaubert

In addition to this as a standalone quote...

If nothing else, one should keep a commonplace book so that they have a treasure house of nifty quotes to use as chapter openers for the books they might write.

Tiago's book follows the general method of the commonplace book, but relies more heavily on a folder-based method and places far less emphasis and value on having a solid index. There isn't any real focus on linking ideas other than putting some things together in the same folder. His experience with the history of the space in feels like it only goes back to some early Ryan Holiday blog posts. He erroneously credits Luhmann with inventing the zettelkasten and Anne-Laure Le Cunff created digital gardens. He's already retracted these in sketch errata here: https://www.buildingasecondbrain.com/endnotes.

I'll give him at least some credit that there is some reasonable evidence that he actually used his system to write his own book, but the number and depth of his references and experience is exceptionally shallow given the number of years he's been in the space, particularly professionally. He also has some interesting anecdotes and examples of various people including and array of artists and writers which aren't frequently mentioned in the note taking space, so I'll give him points for some diversity of players as well. I'm mostly left with the feeling that he wrote the book because of the general adage that "thought leaders in their space should have a published book in their area to have credibility". Whether or not one can call him a thought leader for "re-inventing" something that Rudolphus Agricola and Desiderius Erasmus firmly ensconced into Western culture about 500 years ago is debatable.

Stylistically, I'd call his prose a bit florid and too often self-help-y. The four letter acronyms become a bit much after a while. It wavers dangerously close to those who are prone to the sirens' call of the #ProductivityPorn space.

If you've read a handful of the big articles in the note taking, tools for thought, digital gardens, zettelkasten space, Ahren's book, or regularly keep up with r/antinet or r/Zettelkasten, chances are that you'll be sorely disappointed and not find much insight. If you have friends that don't need the horsepower of Ahrens or zettelkasten, then it might be a reasonable substitute, but then it could have been half the length for the reader.

https://press.princeton.edu/ideas/sherlock-holmes-and-the-history-of-information

If Sherlock Holmes had an excerpting and commonplacing practice, did Arthur Conan Doyle?

He examines archival documents and prehistoric barrows as expertly as mud splashes and tobacco ash, and files the results of his reading and excerpting systematically in a massive collection of notebooks, which he regularly consults.

Worth pulling out the exact reference, but Anthony Grafton indicates that Sherlock Holmes regularly read and "excerpted systematically into a massive collection of notebooks, which he regularly consults."

Tiago is a true pioneer and innovator of our time!

What here is exactly innovative? He's talking about a centuries old idea.

He's just giving you something slightly updated to imitate.

level 2ojboal · 2 hr. agoNot quite understanding the value of Locke's method: far as I understand it, rather than having a list of keywords or phrases, Locke's index is instead based on a combination of first letter and vowel. I can understand how that might be useful for the sake of compression, but doesn't that mean you don't have the benefit of "index as list of keywords/phrases" (or did I miss something)?

Locke's method is certainly a compact one and is specifically designed for notebooks of several hundred pages where you're slowly growing the index as you go within a limited and usually predetermined amount of space. If you're using an index card or digital system where space isn't an issue, then that specific method may not be as ideal. Whichever option you ultimately choose, it's certainly incredibly valuable and worthwhile to have an index of some sort.

For those into specifics, here's some detail about creating an index using Hypothes.is data in Obsidian: https://boffosocko.com/2022/05/20/creating-a-commonplace-book-or-zettelkasten-index-from-hypothes-is-tags/ and here's some detail for how I did it for a website built on WordPress: https://boffosocko.com/2021/09/04/an-index-for-my-digital-commonplace-book/

I'm curious to see how others do this in their tool sets, particularly in ways that remove some of the tedium.

Perhaps it may be helpful to dramatically reframe the question of how to keep a zettelkasten? One page blog posts from people who've only recently seen the idea and are synopsizing it without a year or more practice themselves are highly confusing at best. Can I write something we don't see enough of in spaces relating to zettelkasten? Perhaps we should briefly consider the intellectual predecessor of the slip box?

Start out by forgetting zettelkasten exist. Instead read about what a commonplace book is and how that (simpler) form of note taking works. This short article outlined as a class assignment is a fascinating way to start and has some illustrative examples: https://www.academia.edu/35101285/Creating_a_Commonplace_Book_CPB_. If you're a writer, researcher, or journalist, perhaps Steven Johnson's perspective may be interesting to you instead: https://stevenberlinjohnson.com/the-glass-box-and-the-commonplace-book-639b16c4f3bb

Collect interesting passages, quotes, and ideas as you read. Keep them in a notebook and call it your commonplace book. If you like call these your "fleeting notes" as some do.

As you do this, start building an index of subject headings for your ideas, perhaps using John Locke's method (see: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/john-lockes-method-for-common-place-books-1685).

Once you've got this, you've really mastered the majority of what a zettelkasten is and have a powerful tool at your disposal. If you feel it's useful, you can add a few more tools and variations to your set up.

Next instead of keeping the ideas in a notebook, put them on index cards so that they're easier to sort through, move around, and re-arrange. This particularly useful if you want to use them to create an outline of your ideas for writing something with them.

Next, maybe keep some index cards that have the references and bibliographies from which your excerpting and note taking comes from. Link these bibliographical cards to the cards with your content.

As you go through your notes, ideas, and excerpts, maybe you want to further refine them? Write them out in your own words. Improve their clarity, so that when you go to re-use them, you can simply "excerpt" material you've already written for yourself and you're not plagiarizing others. You can call these improved notes, as some do either "permanent notes" or "evergreen notes".

Perhaps you're looking for more creativity, serendipity, and organic surprise in your system? Next you can link individual notes together. In a paper system you can do this by following one note with another or writing addresses on each card and using that addressing system to link them, but in a digital environment you can link one note to many multiple others that are related. If you're not sure where to start here, look back to your subject headings and pull out cards related to broad categories. Some things will obviously fit more closely than others, so be more selective and only link ideas that are more intimately connected than just the subject heading you've used.

Now when you want to write or create something new on a particular topic, ask your slip box a question and attempt to answer it by consulting your index. Find cards related to the topic, pull out those and place them in a useful order to create an outline perhaps using the cross links that already exist. (You've done that linking work as you went, so why not use it to make things easier now?) Copy the contents into a document and begin editing.

Beyond the first few steps, you're really just creating additional complexity to a system to increase the combinatorial complexity of juxtaposed ideas that you could potentially pull back out of your system for writing more interesting text and generating new ideas. Some people may neither want nor need this sort of complexity in their working lives. If you don't need it, then just keep a simple commonplace book (or commonplace card file) to remind you of the interesting ideas and inspirations you've seen and could potentially reuse throughout your life.

The benefit of this method is that beyond creating your index, you'll always have something useful even if you abandon things later on and quit refining it. If you do go all the way, concentrate on writing out just two short solid ideas every day (Luhmann averaged about 6 per day and Roland Barthes averaged 1 and change). Do it until you have between 500 and 1000 cards (based on some surveys and anecdotal evidence), and you should begin seeing some serendipitous and intriguing results as you use your system for your writing.

We should acknowledge that that (visual) artists and musicians might also keep commonplaces and zettelkasten. As an example, Eminem keeps a zettelkasten, but it is so minimal that it is literally just a box and slips of paper with no apparent organization beyond this. If this fits your style and you don't get any value out of having cards with locators like 3a4b/65m1, then don't do that useless work. Make sure your system is working for you and you're not working for your system.

Sadly, it's generally difficult to find a single blog post that can accurately define what a zettelkasten is, how it's structured, how it works, and why one would want one much less what one should expect from it. Sonke Ahrens does a reasonably good job, but his explanation is an entire book. Hopefully this distillation will get you moving in a positive direction for having a useful daily practice, but without an excessive amount of work. Once you've been at it a while, then start looking at Ahrens and others to refine things for your personal preferences and creative needs.

For anyone who reads music, the sketchbooks literally record the progress of hisinvention. He would scribble his rough, unformed ideas in his pocket notebook andthen leave them there, unused, in a state of suspension, but at least captured withpencil on paper. A few months later, in a bigger, more permanent notebook, you canfind him picking up that idea again, but he’s not just copying the musical idea intoanother book. You can see him developing it, tormenting it, improving it in the newnotebook. He might take an original three-note motif and push it to its next stage bydropping one of the notes a half tone and doubling it. Then he’d let the idea sit therefor another six months. It would reappear in a third notebook, again not copied butfurther improved, perhaps inverted this time and ready to be used in a piano sonata.

Beethoven kept a variation of a waste book in that he kept a pocket notebook for quick capture of ideas. Later, instead of copying them over into a permanent place, he'd translate and amplify on the idea in a second notebook. Later on, he might pick up the idea again in a third notebook with further improvements.

By doing this me might also use the initial ideas as building blocks for more than one individual piece. This is very clever, particularly in musical development where various snippets of music might be morphed into various different forms in ways that written ideas generally can't be so used.

This literally allowed him to re-use his "notes" at two different levels (the written ones as well as the musical ones.)

Beethoven, despite his unruly reputation and wild romantic image, waswell organized. He saved everything in a series of notebooks that were organizedaccording to the level of development of the idea. He had notebooks for rough ideas,notebooks for improvements on those ideas, and notebooks for finished ideas,almost as if he was pre-aware of an idea’s early, middle, and late stages.

Beethoven apparently kept organized notebooks for his work. His system was arranged based on the level of finished work, so he had spaces for rough ideas, improved ideas and others for finished ideas.

Source for this?

http://messnerenglish.weebly.com/who-uses-a-writers-notebook.html

Example of a teacher using the commonplace book tradition within her class, though she frames it as a "writer's notebook". I like the way she uses examples of cultural figures who are doing this same sort of pattern.

It would lack a unique personality or an “alter ego,” which is what Luhmann’s system aimed to create. (9)

Is there evidence that Luhmann's system aimed to create anything from the start in a sort of autopoietic sense? Or is it (more likely) the case that Luhmann saw this sort of "alter ego" emerging over time and described it after-the-fact?

Based on his experiences and note takers and zettelkasten users might expect this outcome now.

Are there examples of prior commonplace book users or note takers seeing or describing this sort of experience in the historical record?

Related to this is the idea that a reader might have a conversation with another author by reading and writing their own notes from a particular text.

The only real difference here is that one's notes and the ability to link them to other ideas or topical headings in a commonplace book or zettelkasten means that the reader/writer has an infinitely growable perfect memory.

https://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/the-scope-and-nature-of-darwins-commonplace-book/

Erasmus Darwin's commonplace book

It is one of the version(s?) published by John Bell based on John Locke's method and is a quarto volume bound in vellum with about 300 sheets of fine paper.

Blank pages 1 to 160 were numbered and filled by Darwin in his own hand with 136 entries. The book was started in 1776 and continued until 1787. Presumably Darwin had a previous commonplace book, but it has not been found and this version doesn't have any experiments prior to 1776, though there are indications that some material has been transferred from another source.

The book contains material on medical records, scientific matters, mechanical and industrial improvements, and inventions.

The provenance of Erasmus Darwin's seems to have it pass through is widow Elizabeth who added some family history to it. It passed through to her son and other descendants who added entries primarily of family related topics. Leonard Darwin (1850-1943), the last surviving son of Charles Darwin gave it to Down House, Kent from whence it was loaned to Erasmus Darwin House in 1999.

The addressing system that many digital note taking systems offer is reminiscent of Luhmann's paper system where it served a particular use. Many might ask themselves if they really need this functionality in digital contexts where text search and other affordances can be more directly useful.

Frequently missed by many, perhaps because they're befuddled by the complex branching numbering system which gets more publicity, Luhmann's paper-based system had a highly useful and simple subject heading index (see: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_SW1_001_V, for example) which can be replicated using either #tags or [[wikilinks]] within tools like Obsidian. Of course having an index doesn't preclude the incredible usefulness of directly linking one idea to potentially multiple others in some branching tree-like or network structure.

Note that one highly valuable feature of Luhmann's paper version was that the totality of cards were linked to a minimum of at least one other card by the default that they were placed into the file itself. Those putting notes into Obsidian often place them into their system as singlet, un-linked notes as a default, and this can lead to problems down the road. However this can be mitigated by utilizing topical or subject headings on individual cards which allows for searching on a heading and then cross-linking individual ideas as appropriate.

As an example, because two cards may be tagged with "archaeology" doesn't necessarily mean they're closely related as ideas. This tends to decrease in likelihood if one is an archaeologist and a large proportion of cards might contain that tag, but will simultaneously create more value over time as generic tags increase in number but the specific ideas cross link in small numbers. Similarly as one delves more deeply into archaeology, one will also come up with more granular and useful sub-tags (like Zooarcheology, Paleobotany, Archeopedology, Forensic Archeology, Archeoastronomy, Geoarcheology, etc.) as their knowledge in sub areas increases.

Concretely, one might expect that the subject heading "sociology" would be nearly useless to Luhmann as that was the overarching topic of both of his zettelkästen (I & II), whereas "Autonomie" was much more specific and useful for cross linking a smaller handful of potentially related ideas in the future.

Looking beyond Luhmann can be highly helpful in designing and using one's own system. I'd recommend taking a look at John Locke's work on indexing (1685) (https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/john-lockes-method-for-common-place-books-1685 is an interesting source, though you're obviously applying it to (digital) cards and not a notebook) or Ross Ashby's hybrid notebook/index card system which is also available online (http://www.rossashby.info/journal/index.html) as an example.

Another helpful tip some are sure to appreciate in systems that have an auto-complete function is simply starting to write a wikilink with various related subject heading words that may appear within your system. You'll then be presented with potential options of things to link to serendipitously that you may not have otherwise considered. Within a digital zettelkasten, the popularly used DYAC (Damn You Auto Complete) may turn into Bless You Auto Complete.

Are there examples of people using The Brain in public as more extensive commonplace books or zettelkasten?

A fantastic example of an extensive mind map from Jerry Michalski using The Brain.

There are lots of interesting links and resources, but on the whole

How many of the nodes actually have specific notes, explicit ideas, annotations, or excerpts within them?

Without these, it's an interesting map and provides some broad context, but removes local specific context of who Jerry is and how he explicitly thinks. One can review the overarching parts to extract what his biases may be based on availability heuristics, but in areas of conflicting ideas which have relatively equal numbers of links within a particular area, one may not be able to discern arguments from each other.

Still a fascinating start and something not commonly seen in the broader literature.

I'll also note that even in a small sample of one video call with Jerry sharing his screen while we talked about a broad sub-topic it's interesting to see his prior contexts as we conversed. I've only ever had similar experiences with Bill Seitz who regularly drops links to his wiki pages in this sort of way or Kevin Marks (usually in text chat contexts and less frequently in video calls/conversations) who drops links to his extensive blogging history which also serves to add his prior thoughts and contextualizations.

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/v48una/randomly_found_out_a_friend_of_mine_uses_note/

Example of a card index note taking method in the wild. Sounds a bit more like a commonplace book rather than a highly organized zettelkasten.

As told in Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman byJames Gleick

Forte cleverly combines a story about Feynman from Genius with a quote about Feynman's 12 favorite problems from a piece by Rota. Did they both appear in Gleick's Genius together and Forte quoted them separately, or did he actively use his commonplace to do the juxtaposition for him and thus create a nice juxtaposition himself or was it Gleick's juxtaposition?

The answer will reveal whether Forte is actively using his system for creative and productive work or if the practice is Gleick's.

Songwriters areknown for compiling “hook books” full of lyrics and musical riffs theymay want to use in future songs. Software engineers build “codelibraries” so useful bits of code are easy to access. Lawyers keep“case files” with details from past cases they might want to refer to inthe future. Marketers and advertisers maintain “swipe files” withexamples of compelling ads they might want to draw from

Nice list of custom names for area specific commonplaces.

digital, we can supercharge these timelessbenefits with the incredible capabilities of technology—searching,sharing, backups, editing, linking, syncing between devices, andmany others

List of some affordance of digital note taking over handwriting: * search * sharing * backups (copies) * editing * linking (automatic?) * syncing to multiple spaces for ease of use

American journalist, author, and filmmaker Sebastian Junger oncewrote on the subject of “writer’s block”: “It’s not that I’m blocked. It’sthat I don’t have enough research to write with power and knowledgeabout that topic. It always means, not that I can’t find the right words,[but rather] that I don’t have the ammunition.”7

7 Tim Ferriss, Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers (New York: HarperCollins, 2017), 421.

relate this to Eminem's "stacking ammo".

There are four essential capabilities that we can rely on a SecondBrain to perform for us:1. Making our ideas concrete.2. Revealing new associations between ideas.3. Incubating our ideas over time.4. Sharpening our unique perspectives.

Does the system really do each of these? Writing things down for our future selves is the thing that makes ideas concrete, not the system itself. Most notebooks don't reveal new associations, we actively have to do that ourselves via memory or through active search and linking within the system itself. The system may help, but it doesn't automatically create associations nor reveal them. By keeping our ideas in one place they do incubate to some extent, but isn't the real incubation taking place in a diffuse way in our minds to come out later?

your Second Brain is a privateknowledge collection designed to serve a lifetime of learning andgrowth, not just a single use case

Based on Tiago Forte's definition of a second brain the primary distinction from a commonplace book is solely that it is digital.

Note here that he explicitly defines a second brain as being private. Historically commonplace books were private affairs though there are examples of them being shared from person to person as well as examples that have been printed.

This digital commonplace book is what I call a Second Brain

Tiago Forte directly equates a "digital commonplace book" with his concept of a "Second Brain" in his book Building a Second Brain.

Why create a new "marketing term" for something that should literally be commonplace!

Popularized in a previous period of information overload, theIndustrial Revolution of the eighteenth and early nineteenthcenturies, the commonplace book was more than a diary or journalof personal reflections

Commonplace books were popularized in the late 1400s/early 1500s in handbooks by Desiderius Erasmus, Philip Melanchthon, Rudolphus Agricola, and others along with the rise and accessibility of printed books.

Would have been nice to have some more background and history on their development and evolution. Mentions of florilegia, vade mecum, others perhaps? Other cultures?

I had discovered somethingvery special

Notice the creation myth being born here? Does he really believe that no one has noticed this before?

What about all the handbook writers who encouraged commonplacing in the 1500s, much less their predecessors?

I’ve spent years studying how prolific writers, artists, and thinkersof the past managed their creative process. I’ve spent countlesshours researching how human beings can use technology to extendand enhance our natural cognitive abilities. I’ve personally

experimented with every tool, trick, and technique available today for making sense of information. This book distills the very best insights I’ve discovered from teaching thousands of people around the world how to realize the potential of their ideas.

All this work just for this? When some basic reading of historical note taking, information management, and intellectual history would have saved him the time and effort? Looking through the references I'm not seeing much before even 2010, so it seems as if he's spent most of his time reinventing the wheel.

Now, this eye-opening and accessible guide shows how you caneasily create your own personal system for knowledge management,otherwise known as a Second Brain.

Marketing speech to convert an old idea (commonplacing) into a new siloed service one needs to pay for.

A revolutionary approach to enhancing productivity,creating flow, and vastly increasing your ability tocapture, remember, and benefit from the unprecedentedamount of information all around us.