- Jun 2022

-

www.civicsoftechnology.org www.civicsoftechnology.org

-

www.insidehighered.com www.insidehighered.com

-

https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/just-visiting/qa-joshua-eyler-how-humans-learn

-

As my colleague Robin Paige likes to say, we are also social beings in a social world. So if we shift things just a bit to think instead about the environments we design and cultivate to help maximize learning, then psychology and sociology are vital for understanding these elements as well.

Because we're "social beings in a social world", we need to think about the psychology and sociology of the environments we design to help improve learning.

Link this to: - Design of spaces like Stonehenge for learning in Indigenous cultures, particularly the "stage", acoustics (recall the ditch), and intimacy of the presentation. - research that children need face-to-face interactions for language acquisition

-

Do we need to start offering PhD’s in higher education pedagogy?

this sounds fun...

-

One of my frustrations with the “science of learning” is that to design experiments which have reasonable limits on the variables and can be quantitatively measured results in scenarios that seem divorced from the actual experience of learning.

Is the sample size of learning experiments really large enough to account for the differences in potential neurodiversity?

How well do these do for simple lectures which don't add mnemonic design of some sort? How to peel back the subtle differences in presentation, dynamism, design of material, in contrast to neurodiversities?

What are the list of known differences? How well have they been studied across presenters and modalities?

What about methods which require active modality shifts versus the simple watch and regurgitate model mentioned in watching videos. Do people do actively better if they're forced to take notes that cause modality shifts and sensemaking?

-

-

www.insidehighered.com www.insidehighered.com

-

How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories Behind Effective College Teaching by Joshua R. Eyler #books/wanttoread<br /> Published in March 2018

Mentioned at the [[Hypothesis Social Learning Summit - Spotlight on Social Reading & Social Annotation]] in the chat in the [[Social Annotation Showcase]]

-

It will be interesting to see where Eyler takes his scholarship post-COVID. I’ll be curious to learn how Eyler thinks of the intersection of learning science and teaching practices in an environment where face-to-face teaching is no longer the default.

Face-to-face teaching and learning has been the majority default for nearly all of human existence. Obviously it was the case in oral cultures, and the tide has shifted a bit with the onset of literacy. However, with the advent of the Internet and the pressures of COVID-19, lots of learning has broken this mold.

How can the affordances of literacy-only modalities be leveraged for online learning that doesn't include significant fact-to-face interaction? How might the zettelkasten method of understanding, sense-making, note taking, and idea generation be leveraged in this process?

-

For college professors, I think the critical contribution of How Humans Learn is that good teaching is constructed, not ordained.

"...good teaching is constructed, not ordained."

-

-

marginalsyllab.us marginalsyllab.us

-

www.researchgate.net www.researchgate.net

-

MemoNote, an annotation-based personal knowledge management tool for teachers

-

-

medium.com medium.com

-

certain sub-currents in their thought. One being the proposition that the original (or translated) texts of the most influential Western books are vastly superior material to study for serious minds than are textbooks that merely give pre-digested (often mis-digested) assessments of the ideas contained therein.

Are some of the classic texts better than more advanced digested texts because they form the building blocks of our thought and society?

Are we training thinkers or doers?

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Chris Moffett@chrismoffettFollows youPhilosophy/Education/Play/Feldenkrais/Drawing/Tech/Shoes/Ducks/...Denton, TXaestheticrelationalexercises.comJoined April 2008

Followed me today after a Liquid Margins event and conversation about note taking follow up methods.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.aeaweb.org www.aeaweb.org

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

The Algebra Project was born.At its core, the project is a five-step philosophy of teaching that can be applied to any concept: Physical experience. Pictorial representation. People talk (explain it in your own words). Feature talk (put it into proper English). Symbolic representation.

The five step philosophy of the Algebra Project: - physical experience - pictorial representation - people talk (explain it in your own words) - feature talk (put it into proper English) - symbolic representation

"people talk" within the Algebra project is an example of the Feynman technique at work

Link this to Sonke Ahrens' method for improving understanding. Are there research links to this within their work?

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/07/education/algebra-project-bob-moses-empowers-students.html

-

-

www.theescalanteprogram.org www.theescalanteprogram.org

-

thecalculusproject.org thecalculusproject.org

-

windowsontheory.org windowsontheory.org

-

There are efforts that actually do work to decrease educational gaps: these include Bob Moses’ Algebra Project, Adrian Mims’ (contact person for one of the letters) Calculus Project, Jaime Escalante (from “stand and deliver”) math program, and the Harlem Children’s Zone.

Mathematical education programs that are attempting to decrease educational gaps: - Bob Moses' Algebra Project - Adrian Mims' Calculus Project - Jaime Escalante math program - Harlem Children's Zone

-

https://windowsontheory.org/2022/04/27/a-personal-faq-on-the-math-education-controversies/

-

essentially all neuroscientists agree that our understanding of the brain is nowhere near the level that it could be used to guide curriculum development.

This looks like an interesting question...

-

Shouldn’t CS and STEM faculty stay out of this debate, and leave it to the math education faculty that are the true subject matter experts?

In querying math professors at many universities, I've discovered that many feel as if they're spending all their time and energy preparing students in the sciences and engineering and very little of their time supporting students in the math department. If one left things up to them, then it's likely that STEM and CS would die on the vine.

-

The inequalities in the US arise from huge disparities in the resources at school, and a highly unequal society at large. I personally think that improving education is much more about support for students, resources, tutoring, teacher training, etc, than whether we teach logarithms using method X or method Y.

-

-

sites.google.com sites.google.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Boaz Barak</span> in Brian Conrad takes down the CMF – Windows On Theory (<time class='dt-published'>06/01/2022 21:35:06</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.maggiedelano.com www.maggiedelano.com

-

A recent book that advocates for this idea is Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized world by David Epstein. Consider reading Cal Newport’s So Good They Can’t Ignore You along side it: So Good They Can’t Ignore You focuses on building up “career capital,” which is important for everyone but especially people with a lot of different interests.1 People interested in interdisciplinary work (including students graduating from liberal arts or other general programs) might seem “behind” at first, but with time to develop career capital these graduates can outpace their more specialist peers.

Similar to the way that bi-lingual/dual immersion language students may temporarily fall behind their peers in 3rd and 4th grade, but rocket ahead later in high school, those interested in interdisciplinary work may seem to lag, but later outpace their lesser specializing peers.

What is the underlying mechanism for providing the acceleration boosts in these models? Are they really the same or is this effect just a coincidence?

Is there something about the dual stock and double experience or even diversity of thought that provides the acceleration? Is there anything in the pedagogy or productivity research space to explain it?

-

-

scottaaronson.blog scottaaronson.blog

-

https://scottaaronson.blog/?p=6389

-

-

Local file Local file

-

There is even significant evidence that expressing our thoughts inwriting can lead to benefits for our health and well-being. 11 One ofthe most cited psychology papers of the 1990s found that“translating emotional events into words leads to profound social,psychological, and neural changes.”

11 James W. Pennebaker, “Writing about Emotional Experiences as a Therapeutic Process,” Psychological Science 8, no. 3 (May 1997), 162–66

Did they mention any pedagogical effects in this work?

How does this relate to the ability to release thoughts from working memory because they're written down and we don't need to spend time and effort trying to remember them? What are the references for this work? I suspect I've got them linked around somewhere...

What other papers/work cover these intersections?

Tags

Annotators

-

- May 2022

-

Local file Local file

-

One of the masters of the school, Hugh (d. 1140 or 1141), wrote a text, the Didascalicon, on whatshould be learned and why. The emphasis differs significantly from that of William of Conches. It isdependent on the classical trivium and quadrivium and pedagogical traditions dating back to St.Augustine and Imperial Rome.

Hugh of St. Victor wrote Didascalicon, a text about what topics should be learned and why. In it, he outlined seven mechanical arts (or technologies) in analogy with the seven liberal arts (trivium and quadrivium) as ways to repair the weaknesses inherit in humanity.

These seven mechanical arts he defines are: - fabric making - armament - commerce - agriculture - hunting - medicine - theatrics

Hugh of St. Victor's description of the mechanical art of commerce here is fascinating. He says "reconciles nations, calms wars, strengthens peace, and turns the private good of individuals into a benefit for all" (doublcheck the original quotation, context, and source). This sounds eerily familiar to the common statement in the United States about trade and commerce.

Link this to the quote from Albie Duncan in The West Wing (season 5?) about trade.

Other places where this sentiment occurs?

Is Hugh of St. Victor the first in history to state this sentiment?

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Active reading to the extreme!

What a clever innovation building on the ideas of the art of memory and Raymond Llull's combinatoric arts!

Does this hit all of the areas of Bloom's Taxonomy? I suspect that it does.

How could it be tied more directly into an active reading, annotating, and note taking practice?

-

-

www.insidehighered.com www.insidehighered.com

-

Third, the post-LMS world should protect the pedagogical prerogatives and intellectual property rights of faculty members at all levels of employment. This means, for example, that contingent faculty should be free to take the online courses they develop wherever they happen to be teaching. Similarly, professors who choose to tape their own lectures should retain exclusive rights to those tapes. After all, it’s not as if you have to turn over your lecture notes to your old university whenever you change jobs.

Own your pedagogy. Send just like anything else out there...

-

-

danallosso.substack.com danallosso.substack.com

-

I returned to another OER Learning Circle and wrote an ebook version of a Modern World History textbook. As I wrote this, I tested it out on my students. I taught them to use the annotation app, Hypothesis, and assigned them to highlight and comment on the chapters each week in preparation for class discussions. This had the dual benefits of engaging them with the content, and also indicating to me which parts of the text were working well and which needed improvement. Since I wasn't telling them what they had to highlight and respond to, I was able to see what elements caught students attention and interest. And possibly more important, I was able to "mind the gaps', and rework parts that were too confusing or too boring to get the attention I thought they deserved.

This is an intriguing off-label use case for Hypothes.is which is within the realm of peer-review use cases.

Dan is essentially using the idea of annotation as engagement within a textbook as a means of proactively improving it. He's mentioned it before in Hypothes.is Social (and Private) Annotation.

Because one can actively see the gaps without readers necessarily being aware of their "review", this may be a far better method than asking for active reviews of materials.

Reviewers are probably not as likely to actively mark sections they don't find engaging. Has anyone done research on this space for better improving texts? Certainly annotation provides a means for helping to do this.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

it's like that's 00:44:13 called like maintenance rehearsal in uh in the science of human memory it's basically just re reintroducing yourself to to the concept how you kind of hammer it into your mind versus elaborative rehearsal is kind of what you're talking about and 00:44:26 what you do which is to uh elaborate on more dimensions that the the the knowledge you know uh that relates to in order to create like more of a a visual stamp on your mind

Dig into research on maintenance rehearsal versus elaborative rehearsal.

-

in human memory they call it external context um so we have 00:35:59 so the external context for instance is the the spatial cues and the other items that are kind of attached to the note right

Theory: The external context of one's physical surroundings (pen, paper, textures, sounds, smells, etc.) combined with the internal context, the learner's psychological state, mood, etc., comprises a potentially closed system where each part props up the other for the best learning outcomes.

Do neurodiversity effects help/hinder this process? What if people are missing one or more of these bits of contextualization? What does the literature look like in this space? Research?

-

- Apr 2022

-

read.bookcreator.com read.bookcreator.com

-

A digital book creation platform geared toward elementary students and teachers.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

-

Researchdemonstrates that students who engage in active learning acquire a deeperunderstanding of the material, score higher on exams, and are less likely to failor drop out.

Active learning is a pedagogical structure whereby a teacher presents a problem to a group of students and has them (usually in smaller groups) collectively work on the solutions together. By talking and arguing amongst themselves they actively learn together not only how to approach problems, but to come up with their own solutions. Teachers can then show the correct answer, discuss why it was right and explain how the alternate approaches may have gone wrong. Research indicates that this approach helps provide a deeper understanding of the materials presented this way, that students score higher on exams and are less likely to either fail or drop out of these courses.

Active learning sounds very similar to the sorts of approaches found in flipped classrooms. Is the overlap between the two approaches the same, or are there parts of the Venn diagrams of the two that differ, and, if so, how do they differ? Which portions are more beneficial?

Does this sort of active learning approach also help to guard against "group think" as the result of comparing solutions from various groups? How might this be applied to democracy? Would separate versions of committees that then convene to compare notes and come up with solutions improve the quality of solutions?

-

A 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy ofSciences supports Wieman’s hunch. Tracking the intellectual advancement ofseveral hundred graduate students in the sciences over the course of four years,its authors found that the development of crucial skills such as generatinghypotheses, designing experiments, and analyzing data was closely related to thestudents’ engagement with their peers in the lab, and not to the guidance theyreceived from their faculty mentors.

Learning has been shown to be linked to engagement with peers in social situations over guidance from faculty mentors.

Cross reference: David F. Feldon et al., “Postdocs’ Lab Engagement Predicts Trajectories of PhD Students’ Skill Development,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (October 2019): 20910–16

Are there areas where this is not the case? Are there areas where this is more the case than not?

Is it our evolution as social animals that has heightened this effect? How could this be shown? (Link this to prior note about social evolution.)

Is it the ability to scaffold out questions and answers and find their way by slowly building up experience with each other that facilitates this effect?

Could this effect be seen in annotating texts as well? If one's annotations become a conversation with the author, is there a learning benefit even when the author can't respond? By trying out writing about one's understanding of a text and seeing where the gaps are and then revisiting the text to fill them in, do we gain this same sort of peer engagement? How can we encourage students to ask questions to the author and/or themselves in the margins? How can we encourage them to further think about and explore these questions? Answer these questions over time?

A key part of the solution is not just writing the annotations down in the first place, but keeping them, reviewing over them, linking them together, revisiting them and slowly providing answers and building solutions for both themselves and, by writing them down, hopefully for others as well.

-

Researchers are also experimenting with “haptic” signals: physical nudgesdelivered via special gloves or tools that help mold a novice’s movementpatterns into those of an expert.

-

Research has shown that,across disciplines, experts look in ways different from novices: they take in thebig picture more rapidly and completely, while focusing on the most importantaspects of the scene; they’re less distracted by visual “noise,” and they shiftmore easily among visual fields, avoiding getting stuck.

Experts have more practiced levels of visual perception of surroundings that provide them with information more quickly than novices who don't yet know what or where to focus their attention. Teaching with eye tracking technology might help to bridge the gap between novice and expert more quickly.

-

But reenacting the experience of being a novice need not be so literal; expertscan generate empathy for the beginner through acts of the imagination, changingthe way they present information accordingly. An example: experts habituallyengage in “chunking,” or compressing several tasks into one mental unit. Thisfrees up space in the expert’s working memory, but it often baffles the novice,for whom each step is new and still imperfectly understood. A math teacher mayspeed through an explanation of long division, not remembering or recognizingthat the procedures that now seem so obvious were once utterly inscrutable.Math education expert John Mighton has a suggestion: break it down into steps,then break it down again—into micro-steps, if necessary.

When teaching novices, experts utilize chunking, or breaking up an idea into smaller units. While this may help free up cognitive space from the expert's point of view it exhibits a lack of empathy for the novice who may need expert-sized chunks broken down into micro-sized chunks which are more appropriate to their beginner status.

While the benefits of chunking can be useful to both sets of participants, the sizes of the chunks need to be relative to one's prior experience to leverage their benefit.

-

instructors and experts must also become more legible models. This can beaccomplished through what philosopher Karsten Stueber calls “re-enactiveempathy”: an appreciation of the challenges confronting the novice that isproduced by reenacting what it was like to have once been a beginner oneself.

-

Our systems of academic education and workplace training rely on expertsteaching novices, but they rarely take into account the blind spots that expertsacquire by virtue of being experts.

-

Kenneth Koedinger, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and thedirector of its Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center, estimates that experts areable to articulate only about 30 percent of what they know.

-

As Smith notes, the emulation of model texts was once a standard feature ofinstruction in legal writing; it fell out of favor because of concern that thepractice would fail to foster a capacity for independent thinking. The carefulobservation of how students actually learn, informed by research on the role ofcognitive load, may be bringing models back into fashion.

-

In the course of teaching hundredsof first-year law students, Monte Smith, a professor and dean at Ohio StateUniversity’s law school, grew increasingly puzzled by the seeming inability ofhis bright, hardworking students to absorb basic tenets of legal thinking and toapply them in writing. He came to believe that the manner of his instruction wasdemanding more from them than their mental bandwidth would allow. Studentswere being asked to employ a whole new vocabulary and a whole new suite ofconcepts, even as they were attempting to write in an unaccustomed style and anunaccustomed form. It was too much, and they had too few mental resources leftover to actually learn.

This same analogy also works in advanced mathematics courses where students are often learning dense and technical vocabulary and then moments later applying it directly to even more technical ideas and proofs.

How might this sort of solution from law school be applied to abstract mathematics?

-

This act of imitation relieves students of some of theirmental burden, Robinson notes, allowing them to devote the bulk of theircognitive bandwidth to the content of the assignment

By providing students solid examples of work that is expected of them they can more easily imitate the examples which frees up cognitive bandwidth so that they can focus their time and attention on creating their own content related to particular assignments.

-

Seeing examples of outstanding work motivates students by givingthem a vision of the possible. How can we expect students to produce first-ratework, he asks, when they have no idea what first-rate work looks like?

Showing students examples of work and processes that they can imitate will fuel their imaginations and capabilities rather than stifle them.

-

In studies comparing European American children withMayan children from Guatemala, psychologists Maricela Correa-Chávez andBarbara Rogoff asked children from each culture to wait while an adultperformed a demonstration—folding an origami shape—for another childnearby. The Mayan youth paid far more sustained attention to the demonstration—and therefore learned more—than the American kids, who were oftendistracted or inattentive. Correa-Chávez and Rogoff note that in Mayan homes,children are encouraged to carefully observe older family members so that theycan learn how to carry out the tasks of the household, even at very young ages.

American children aren't encouraged to as attentive imitators as their foreign counterparts and this can effect their learning processes.

-

While it was once regarded as a low-level, “primitive” instinct, researchers arecoming to recognize that imitation—at least as practiced by humans, includingvery young ones—is a complex and sophisticated capacity. Although non-humananimals do imitate, their mimicry differs in important ways from ours. Forexample, young humans’ copying is unique in that children are quite selectiveabout whom they choose to imitate. Even preschoolers prefer to imitate peoplewho have shown themselves to be knowledgeable and competent. Researchshows that while toddlers will choose to copy their mothers rather than a personthey’ve just met, as children grow older they become increasingly willing tocopy a stranger if the stranger appears to have special expertise. By the time achild reaches age seven, Mom no longer knows best.

Studies have shown that humans are highly selective about whom they choose to imitate. Children up to age seven show a propensity to imitate their parents over strangers and after that they primarily imitate people who have shown themselves to be knowledgeable and competent within an area of expertise.

This has applications to teaching with respect to math shaming. A teacher who says that math is personally hard for them is likely to be signaling to students that what they're teaching is not based on experience and expertise and thus demotivating the student from following and imitating their example.

-

Shenkar wouldlike to see students in business schools and other graduate programs taking

courses on effective imitation.

If imitation is so effective, what would teaching imitation to students look like in a variety of settings including, academia, business, and other areas?

Is teaching by way of imitation the best method for the majority of students? Are there ways to test this versus other methods for broad effectiveness?

How can we better leverage imitation in teaching for application to the real world?

-

Researchers have demonstrated, for instance, that intentionallyimitating someone’s accent allows us to comprehend more easily the words theperson is speaking (a finding that might readily be applied to second-languagelearning).

-

And indeed, a study conducted by Roze and his colleagues found that two anda half years after their neurological rotation, medical students who hadparticipated in the miming program recalled neurological signs and symptomsmuch better than students who had received only conventional instructioncentered on lectures and textbooks. Medical students who had simulated theirpatients’ symptoms also reported that the experience deepened theirunderstanding of neurological illness and increased their motivation to learnabout it.

-

Imitating such forms with one’sown face and body is an even more effective means of learning, maintainsEmmanuel Roze, who introduced his “mime-based role-play training program”to the students at Pitié-Salpêtrière in 2015. Roze, a consulting neurologist at thehospital and a professor of neurology at Sorbonne University, had becomeconcerned that traditional modes of instruction were not supporting students’acquisition of knowledge, and were not dispelling students’ apprehension in theface of neurological illness. He reasoned that actively imitating the distinctivesymptoms of such maladies—the tremors of Parkinson’s, the jerky movementsof chorea, the slurred speech of cerebellar syndrome—could help students learnwhile defusing their discomfort.

Training students to be able to imitate the symptoms of disease so that they may demonstrate them to others is an effective form of context shifting. It allows the students to shift from a written or spoken description of the disease to a physical interpretation of it for themselves which also entails more cognitive work than even seeing a particular patient with the problem and identifying it correctly. The need to mentally internalize the issue and then physically recreate it helps in the acquisition of the knowledge.

Role playing or putting oneself into the shoes of another is another good example of creating a mental shift in context.

Getting medical students to play out the symptoms of patients can help to diffuse their social discomfort in dealing with these patients.

If this practice were used on broader scales might it also help to normalize issues that patients face and dispel social stigma toward them?

-

Jean-Martin Charcot, the nineteenth-century physician known as the father ofneurology, practiced and taught at this very institution. Charcot brought hispatients onstage with him as he lectured, allowing his students to see firsthandthe many forms neurological disease could take

Nineteenth-century physician Jean-Martin Charcot, known as the father of neurology, brought patients to his lectures at Universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris to allow students to see forms of disease first hand.

When was the medical teaching practice of "rounds" instituted?

-

if weare to extend our thinking with others’ expertise, we must find better ways ofeffecting an accurate transfer of knowledge from one mind to another.

-

crucial difference between traditional apprenticeships and modern schooling: inthe former, “learners can see the processes of work,” while in the latter, “theprocesses of thinking are often invisible to both the students and the teacher.”Collins and his coauthors identified four features of apprenticeship that could beadapted to the demands of knowledge work: modeling, or demonstrating the taskwhile explaining it aloud; scaffolding, or structuring an opportunity for thelearner to try the task herself; fading, or gradually withdrawing guidance as thelearner becomes more proficient; and coaching, or helping the learner throughdifficulties along the way.

This is what’s known as a cognitive apprenticeship, a term coined by Allan Collins, now a professor emeritus of education at Northwestern University. In a 1991 article written with John Seely Brown and Ann Holum, Collins noted a

In a traditional apprenticeship, a learner watches and is able to imitate the master process and work. In a cognitive apprenticeship the process of thinking is generally invisible to both the apprentice and the teacher. The problem becomes how to make the thinking processes more tangible and visible to the learner.

Allan Collins, John Seely Brown, and Ann Holum identified four pedagogical methods in apprenticeships that can also be applied to cognitive apprenticeships: - modeling: demonstrating a task while focusing on describing and explaining the steps and general thinking about the problem out loud - scaffolding: structuring a task to encourage and allow the learner the ability to try it themself - fading: as the learner gains facility and confidence in the process, gradually removing the teacher's guidance - coaching: as necessary, the teacher provides tips and suggestions to the learner to prompt them through potential difficulties

Tags

- efficiency

- attention

- monkey see monkey do

- experience

- medical education

- fading

- empathy

- re-enactive empathy

- context shifting

- conversations with the text

- chunking

- analogies

- imitation for learning

- lead by example

- apprenticeships

- democracy

- expertise

- mathematics

- competence

- math shaming

- coaching

- imitation

- Karsten Stueber

- medical rounds

- Jean-Martin Charcot

- modeling behavior

- haptic feedback

- scaffolding

- annotations

- beginners

- comprehension

- language acquisition

- mental bandwidth

- committees

- pedagogy

- cognitive apprenticeships

- internalizing knowledge

- annotation for learning

- knowledge work

- open questions

- groups

- mathematics definitions

- medical school

- flipped classrooms

- knowledge scaffolding

- role playing

- business school

- eye tracking

- group think

- peer engagement

- indigenous ways of knowing

- learning techniques

- AnnoConvo

- evolution

- selectivity

- active learning

Annotators

-

-

sambleckley.com sambleckley.com

-

We’re going to build the query from the inside out; concentrate on what each step means and how we combine them, not what it will return if run in isolation.

-

-

hechingerreport.org hechingerreport.org

-

homework compliance

A major point in Chloé Collins's text is that traditional annotations risk feeling like a chore, done to fulfill teachers' requirements. In Collins's experience, the collaborative dimension of social annotation helps make it into something learners do for themselves.

https://eductive.ca/en/resource/real-life-story/boosting-engagement-with-social-annotation/

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Much of Barthes’ intellectual and pedagogical work was producedusing his cards, not just his published texts. For example, Barthes’Collège de France seminar on the topic of the Neutral, thepenultimate course he would take prior to his death, consisted offour bundles of about 800 cards on which was recorded everythingfrom ‘bibliographic indications, some summaries, notes, andprojects on abandoned figures’ (Clerc, 2005: xxi-xxii).

In addition to using his card index for producing his published works, Barthes also used his note taking system for teaching as well. His final course on the topic of the Neutral, which he taught as a seminar at Collège de France, was contained in four bundles consisting of 800 cards which contained everything from notes, summaries, figures, and bibliographic entries.

Given this and the easy portability of index cards, should we instead of recommending notebooks, laptops, or systems like Cornell notes, recommend students take notes directly on their note cards and revise them from there? The physicality of the medium may also have other benefits in terms of touch, smell, use of colors on them, etc. for memory and easy regular use. They could also be used physically for spaced repetition relatively quickly.

Teachers using their index cards of notes physically in class or in discussions has the benefit of modeling the sort of note taking behaviors we might ask of our students. Imagine a classroom that has access to a teacher's public notes (electronic perhaps) which could be searched and cross linked by the students in real-time. This would also allow students to go beyond the immediate topic at hand, but see how that topic may dovetail with the teachers' other research work and interests. This also gives greater meaning to introductory coursework to allow students to see how it underpins other related and advanced intellectual endeavors and invites the student into those spaces as well. This sort of practice could bring to bear the full weight of the literacy space which we center in Western culture, for compare this with the primarily oral interactions that most teachers have with students. It's only in a small subset of suggested or required readings that students can use for leveraging the knowledge of their teachers while all the remainder of the interactions focus on conversation with the instructor and questions that they might put to them. With access to a teacher's card index, they would have so much more as they might also query that separately without making demands of time and attention to their professors. Even if answers aren't immediately forthcoming from the file, then there might at least be bibliographic entries that could be useful.

I recently had the experience of asking a colleague for some basic references about the history and culture of the ancient Near East. Knowing that he had some significant expertise in the space, it would have been easier to query his proverbial card index for the lived experience and references than to bother him with the burden of doing work to pull them up.

What sorts of digital systems could help to center these practices? Hypothes.is quickly comes to mind, though many teachers and even students will prefer to keep their notes private and not public where they're searchable.

Another potential pathway here are systems like FedWiki or anagora.org which provide shared and interlinked note spaces. Have any educators attempted to use these for coursework? The closest I've seen recently are public groups using shared Roam Research or Obsidian-based collections for book clubs.

-

-

joanakompa.com joanakompa.com

-

Towards a social, rather than a technical perspective in media-supported education: The concept of hybrid space-time

Very salient!

-

-

-

Pedagogues considered marginal annotations as the first, optional step towardthe ultimate goal of forming a free-standing collection of excerpts from one’sreading. In practice, of course, readers could annotate their books without takingthe further step of copying excerpts into notebooks.

Annotations or notes are definitely the first step towards having a collection of excerpts from one's reading. Where to put them can be a useful question though. Should they be in the margins for ease of creation or should they go into a notebook. Both of these methods may require later rewriting/revision or even moving into a more convenient permanent place. The idea "don't repeat yourself" (DRY) in programming can be useful to keep in mind, but the repetition of the ideas in writing and revision can help to quicken the memory as well as potentially surface additional ideas that hadn't occurred upon the notes' original capture.

-

ostension (or teaching by showing in person)

-

One of his last works, the Aurifodina, “The Mine of All Arts and Sci-ences, or the Habit of Excerpting,” was printed in 1638 (in 2,000 copies) andin another fourteen editions down to 1695 and spawned abridgments in Latin(1658), German (1684), and English.

Simply the word abridgement here leads me to wonder:

Was the continual abridgement of texts and excerpting small pieces for later use the partial cause of the loss of the arts of memory? Ars excerpendi ad infinitum? It's possible that this, with the growth of note taking practices, continual information overload, and other pressures for educational reform swamped the prior practices.

For evidence, take a look at William Engel's work following the arts of memory in England and Europe to see if we can track the slow demise by attrition of the descriptions and practices. What would such a study show? How might we assign values to the various pressures at play? Which was the most responsible?

Could it have also been the slow, inexorable death of many of these classical means of taking notes as well? How did we loose the practices of excerpting for creating new ideas? Where did the commonplace books go? Where did the zettelkasten disappear to?

One author, with a carefully honed practice and the extant context of their life writes some brief notes which get passed along to their students or which are put into a new book that misses a lot of their existing context with respect to the new readers. These readers then don't know about the attrition happening and slowly, but surely the knowledge goes missing amidst a wash of information overload. Over time the ideas and practices slowly erode and are replaced with newer techniques which may not have been well tested or stood the test of time. One day the world wakes up and the common practices are no longer of use.

This is potentially all the more likely because of the extremely basic ideas underpinning some of memory and note taking. They seem like such basic knowledge we're also prone to take them for granted and not teach them as thoroughly as we ought.

How does one juxtapose this with the idea of humanist scholars excerpting, copying, and using classical texts with a specific eye toward preventing the loss of these very classical texts?

Is this potentially the idea of having one's eye on a particular target and losing sight of other creeping effects?

It's also difficult to remember what it was like when we ourselves didn't know something and once that is lost, it can be harder and harder to teach newcomers.

-

enable the blogger to share his or her observations from readings or experiencewith others, just as some seventeenth- century pedagogues advocated sharingnotes within a group.

Blogs

Blogging is a form of public note sharing that isn't dissimilar to seventeenth-century note sharing practices in group settings.

Tags

- definitions

- blogging

- pedagogy

- ostension

- disappearance of the art of memory

- zettelkasten

- information overload

- ars excerpendi

- disappearance of note taking practices

- memory

- note taking

- context collapse

- analogies

- marginalia

- notebooks

- forgetting

- note sharing

- don't repeat yourself

- mnemotechnics

- abridgement

- commonplace books

- note taking methods

- education reform

- annotations

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.sfchronicle.com www.sfchronicle.com

-

yaledailynews.com yaledailynews.com

-

“The exam is open book and open note, but you MUST NOT work with another person while taking it,” the instructions read. “You also MUST not copy/paste anything directly from ANY source other than your own personal notes. This includes no copy/pasting from lecture slides, from the internet, or from any of the readings. All short answers must be compiled in your own words.”

While students apparently have ignored the instructions in the past resulting in breaches of academic integrity, teachers can prompt active learning even during exams by prompting students to write answers to questions on open book/open notes in their own words.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>I love this graphic organiser created by FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning) which encourages students to write down what they have found and explain the relevance. Lots of free resources like this can be found on the FOSIL group website here https://t.co/3uhWQNOr14 pic.twitter.com/ijH98bcc5U

— Elizabeth Hutchinson FCLIP BEM (@Elizabethutch) October 27, 2021

-

-

www.cultofpedagogy.com www.cultofpedagogy.com

-

-

In the meantime, you can add another layer of scaffolding by simply adding more verbal cues to your learning experiences (Kiewra, 2002). Research shows that simply saying things like, “This is an important point,” or “Be sure to add this to your notes,” instructors can ensure that students include key ideas in their notes. Providing written cues on the board or a slideshow can also help students structure their notes and decide what information to include.

Verbal cues can be a useful method of scaffolding for students when note taking. Examples of this behavior are statements like "this is important" or "be sure to capture this in your notes".

-

This strategy has been shown to substantially increase student achievement across all grade levels (elementary through college) and with students who present with various disabilities (Haydon, Mancil, Kroeger, McLeskey, & Lin, 2011).

Guided notes (or skeletal notes with broad topic headings) are a useful pedagogical scaffolding technique to encourage students to take notes. Methods like this have been show to improve student outcomes at all levels as well as for those with disabilities.

-

-

www.core-econ.org www.core-econ.org

-

A New York Times article uses the same temperature dataset you have been using to investigate the distribution of temperatures and temperature variability over time. Read through the article, paying close attention to the descriptions of the temperature distributions.

Unfortunately, like most NYT content, this article is behind a paywall. I'm partly reading this as I plan to develop a set of open education resources myself and the problem of how to manage dead/unavailable links looks like a key stumbling block.

-

-

super-memory.com super-memory.com

-

Personalized examples are very resistant to interference and can greatly reduce your learning time

Creating links to one's own personal context can help one to both learn and retain new material.

-

In the example below you will save time if you use a personal reference rather than trying to paint a picture that would aptly illustrate the question

More closely associating new ideas to one's own personal life helps to create and expand the context of the learning to what one already knows.

Within the context of Bloom's Taxonomy, doing this shows that one understands and is already applying and even doing a bit of creating, at least internally.

Should 'understanding' come before 'remembering' in Bloom's taxonomy? That seems more logical to me.

Bloom's Taxonomy mirrors the zettelkasten method

(Recall Bloom's Taxonomy: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create)

One needs to be able to generally understand an idea(s) to be able to write it down clearly in one's own words. Regular work within a zettelkasten helps to reinforce memory of ideas for understanding and retention. Applying the knowledge to other situations happens almost naturally with the combinatorial creativity that occurs within a zettelkasten. Analysis is heavily encouraged as one takes new information and links it to prior knowledge and ideas; this is also concurrent with the application of knowledge. Being able to compare and contrast two ideas on separate cards is also part of the analysis portions of Bloom's taxonomy which also leads into the evaluation phase. Finally, one of the most important reasons for keeping a zettelkasten is to use it to generate or create new ideas and thoughts and then write them down in articles, books, or other media in a clear and justified manner.

-

One of the most effective ways of enhancing memories is to provide them with a link to your personal life.

Personalizing ideas using existing memories is a method of brining new knowledge into one's own personal context and making them easier to remember.

link this to: - the pedagogical idea of context shifting as a means of learning - cards about reframing ideas into one's own words when taking notes

There is a solid group of cards around these areas of learning.

Random thought: Personal learning networks put one into a regular milieu of people who are talking and thinking about topics of interest to the learner. Regular discussions with these people helps one's associative memory by tying the ideas into this context of people with relation to the same topic. Humans are exceedingly good at knowing and responding to social relationships and within a personal learning network, these ties help to create context on an interpersonal level, but also provide scaffolding for the ideas and learning that one hopes to do. These features will tend to reinforce each other over time.

On the flip side of the coin there is anecdotal evidence of friends taking courses together because of their personal relationships rather than their interest in the particular topics.

-

- Mar 2022

-

hackeducation.com hackeducation.com

-

Too many people who try to predict the future of education and education technology have not bothered to learn the alphabet — the grammar of schooling, to borrow a phrase from education historian Larry Cuban. That grammar includes the beliefs and practices and memory of schooling — our collective memory, not just our own personal experiences of school. That collective memory — that's history.

Collective memory is our history.

Something interesting here tying collective memory to education. Dig into this and expand on it.

-

-

wvupressonline.com wvupressonline.com

-

Human minds are made of memories, and today those memories have competition. Biological memory capacities are being supplanted, or at least supplemented, by digital ones, as we rely on recording—phone cameras, digital video, speech-to-text—to capture information we’ll need in the future and then rely on those stored recordings to know what happened in the past. Search engines have taken over not only traditional reference materials but also the knowledge base that used to be encoded in our own brains. Google remembers, so we don’t have to. And when we don’t have to, we no longer can. Or can we? Remembering and Forgetting in the Age of Technology offers concise, nontechnical explanations of major principles of memory and attention—concepts that all teachers should know and that can inform how technology is used in their classes. Teachers will come away with a new appreciation of the importance of memory for learning, useful ideas for handling and discussing technology with their students, and an understanding of how memory is changing in our technology-saturated world.

How much history is covered here?

Will mnemotechniques be covered here? Spaced repetition? Note taking methods in the commonplace book or zettelkasten traditions?

-

-

-

These ways of knowinghave inherent value and are leading Western scientists to betterunderstand celestial phenomena and the history and heritage thisconstitutes for all people.

The phrase "ways of knowing" is fascinating and seems to have a particular meaning across multiple contexts.

I'd like to collect examples of its use and come up with a more concrete definition for Western audiences.

How close is it to the idea of ways (or methods) of learning and understanding? How is it bound up in the idea of pedagogy? How does it relate to orality and memory contrasted with literacy? Though it may not subsume the idea of scientific method, the use, evolution, and refinement of these methods over time may generally equate it with the scientific method.

Could such an oral package be considered a learning management system? How might we compare and contrast these for drawing potential equivalencies of these systems to put them on more equal footing from a variety of cultural perspectives? One is not necessarily better than another, but we should be able to better appreciate what each brings to the table of world knowledge.

-

-

www.cs.umd.edu www.cs.umd.edu

-

A major advance in user interfaces that supports creative exploration would the capacity to go back in time, to review and manipulate the history of actions taken during an entire session. Users will be able to see all the steps in designing an engine and change an early design decision. They will be able to extract sections of the history to replay them or to convert into permanent macros that can be applied in similar situations. Extracting and replaying sections of history is a form of direct man ipulation programming. It enables users to explore every alternative in a decision-making situation, and then chose the one with the most favorable outcomes.

While being able to view the history of a problem space from the perspective of a creation process is interesting, in reverse, it is also an interesting way to view a potential learning experience.

I can't help but think about the branching tree networks of knowledge in some math texts providing potential alternate paths through the text to allow learners to go from novice to expert in areas in which they're interested. We need more user interfaces like this.

-

Future tools will provide standard ized learning streams to help novices perform basic tasks and scaffolding that wraps the tool with guidance as users acquire expertise. Experts will be able to record their insights for others and make macros to speed common tasks by novices.

We've been promised this for ages, but where is it? Shouldn't it be here by now if it were deliverable or actualizable?

What are the problems in solving this?

How might one automate the Markov monkey?

-

-

-

To signify that an angle is acute, Jeffreys taught them, “make Pac-Man withyour arms.” To signify that it is obtuse, “spread out your arms like you’re goingto hug someone.” And to signify a right angle, “flex an arm like you’re showingoff your muscle.” For addition, bring two hands together; for division, make akarate chop; to find the area of a shape, “motion as if you’re using your hand asa knife to butter bread.”

Math teacher Brendan Jeffreys from the Auburn school district in Auburn, WA created simple hand gestures to accompany or replace mathematical terms. Examples included making a Pac-Man shape with one's arms to describe an acute angle, spreading one's arms wide as if to hug someone to indicate an obtuse angle, or flexing your arm to show your muscles to indicate a right triangle. Other examples included a karate chop to indicate division or a motion imitating using a knife to butter bread to indicate finding the area of a shape.

-

Washington State mathteacher Brendan Jeffreys turned to gesture as a way of easing the mental loadcarried by his students, many of whom come from low-income households,speak English as a second language, or both. “Academic language—vocabularyterms like ‘congruent’ and ‘equivalent’ and ‘quotient’—is not something mystudents hear in their homes, by and large,” says Jeffreys, who works for theAuburn School District in Auburn, a small city south of Seattle. “I could see thatmy kids were stumbling over those words even as they were trying to keep trackof the numbers and perform the mathematical operations.” So Jeffreys devised aset of simple hand gestures to accompany, or even temporarily replace, theunfamiliar terms that taxed his students’ ability to carry out mental math.

Mathematics can often be more difficult compared to other subjects as students learning new concepts are forced not only to understand entirely new concepts, but simultaneously are required to know new vocabulary to describe those concepts. Utilizing gestures to help lighten the cognitive load of the new vocabulary to allow students to focus on the concepts and operations can be invaluable.

-

A familiar example ofsuch offloading is the way young children count on their fingers when workingout a math problem. Their fingers “hold” an intermediate sum so that their mindsare free to think about the mathematical operation they must execute (addition,subtraction) to reach the final answer.

Children counting on their fingers is an example of offloading cognitive load by using proprioception.

Different cultures use different finger sequences (particularly for the number 3) for counting up.

-

designed gestures can lighten our mentalload.

Designed (or intentional) gestures can function to lighten the cognitive load of teaching by engaging multiple pathways simultaneously.

-

Evaluations of the platform show that users who follow the avatar inmaking a gesture achieve more lasting learning than those who simply hear theword. Gesturing students also learn more than those who observe the gesture butdon’t enact it themselves.

Manuela Macedonia's research indicates that online learners who enact specific gestures as they learn words learn better and have longer retention versus simply hearing words. Students who mimic these gestures also learn better than those who only see the gestures and don't use them themselves.

How might this sort of teacher/avatar gesturing be integrated into online methods? How would students be encouraged to follow along?

Could these be integrated into different background settings as well to take advantage of visual memory?

Anecdotally, I remember some Welsh phrases from having watched Aran Jones interact with his cat outside on video or his lip syncing in the empty spaces requiring student responses. Watching the teachers lips while learning can be highly helpful as well.

-

In a study published in 2020, for example, Macedonia and a group of sixcoauthors compared study participants who had paired new foreign-languagewords with gestures to those who had paired the learning of new words withimages of those words. The researchers found evidence that the motor cortex—the area of the brain that controls bodily movement—was activated in thegesturing group when they reencountered the vocabulary words they hadlearned; in the picture-viewing group, the motor cortex remained dormant. The“sensorimotor enrichment” generated by gesturing, Macedonia and hercoauthors suggest, helps to make the associated word more memorable

Manuela Macedonia and co-authors found that pairing new foreign words with gestures created activity in the motor cortex which helped to improve the associative memory for the words and the movements. Using images of the words did not create the same motor cortex involvement.

It's not clear which method of association is better, at least as written in The Extended Mind. Was one better than the other? Were they tested separately, together, and in a control group without either? Surely one would suspect that using both methods together would be most beneficial.

-

Kerry Ann Dickson, an associate professor of anatomy and cell biology atVictoria University in Australia, makes use of all three of these hooks when sheteaches. Instead of memorizing dry lists of body parts and systems, her studentspractice pretending to cry (the gesture that corresponds to the lacrimal gland/tearproduction), placing their hands behind their ears (cochlea/hearing), and swayingtheir bodies (vestibular system/balance). They feign the act of chewing(mandibular muscles/mastication), as well as spitting (salivary glands/salivaproduction). They act as if they were inserting a contact lens, as if they werepicking their nose, and as if they were engaging in “tongue-kissing” (motionsthat represent the mucous membranes of the eye, nose, and mouth, respectively).Dickson reports that students’ test scores in anatomy are 42 percent higher whenthey are taught with gestures than when taught the terms on their own.

Example of the use of visual, auditory, and proprioceptive methods used in the pedagogy of anatomy.

-

The use of gesture supplies a temporary scaffold that supports theseundergraduates’ still wobbly understanding of the subject as they fix theirknowledge more firmly in place.

Gesturing supplies a visual scaffolding which allows one to affix their budding understanding of new concepts into a more permanent structure.

-

“It is from the attempt of expressing themselves thatunderstanding evolves, rather than the other way around,” he maintains.

—Woff-Michael Roth

Actively attempting to express oneself is one of the best methods of evolving one's understanding.

Link this to the ideas related to being forced to actively manufacture the answer to a question is one of the best ways to learn.

-

The study’s authors suggest that this discrepancy may emerge fromdifferences in boys’ and girls’ experience: boys are more likely to play withspatially oriented toys and video games, they note, and may become morecomfortable making spatial gestures as a result. Another study, this oneconducted with four-year-olds, reported that children who were encouraged togesture got better at rotating mental objects, another task that draws heavily onspatial-thinking skills. Girls in this experiment were especially likely to benefitfrom being prompted to gesture.

The gender-based disparity of spatial thinking skills between boys and girls may result from the fact that at an early age boys are more likely to play with spatially oriented toys and video games. Encouraging girls to do more spatial gesturing at an earlier age can dramatically close this spatial thinking gap.

-

Even adults, when asked to gesture more, respond byincreasing their rate of gesture production (and consequently speak morefluently); when teachers are told about the importance of gesturing to studentlearning, and encouraged to make more gestures during instruction, theirstudents make greater learning gains as a result.

It's been shown that merely asking people to gesture more will increase their rates of gesturing. In educational settings this improves both teachers' instruction methods as well as the learning and retention by students.

-

A simple request to “move your handsas you explain that” may be all it takes. For children in elementary school, forexample, encouraging them to gesture as they work on math problems leadsthem to discover new problem-solving strategies—expressed first in their handmovements—and to learn more successfully the mathematical concept understudy.

Given the benefits of gesturing, teachers can improve their pedagogy simply by encouraging their students to move their hands while explaining things or working on problems.

Studies with elementary school children have shown that if they gesture while solving math problems led them to discover and understand new concepts and problem solving strategies.

link this with prior idea of handwriting out annotations/notes as well as drawing and sketchnoting ideas from lectures

Students reviewing over Cornell notes also be encouraged to use their hands while answering their written review questions.

-

Research suggeststhat making these motions will improve our own performance: people who

gesture as they teach on video, it’s been found, speak more fluently and articulately, make fewer mistakes, and present information in a more logical and intelligible fashion.

Teachers who gesture as they teach have been found to make fewer mistakes, speak more fluently/articulately, and present their lessons in a more intelligible and logical manner.

-

Yet the most popular and widely viewed instructional videos available onlinelargely fail to leverage the power of gesture, according to a team ofpsychologists from UCLA and California State University, Los Angeles. Theresearchers examined the top one hundred videos on YouTube devoted toexplaining the concept of standard deviation, an important topic in the study ofstatistics. In 68 percent of these recordings, they report, the instructor’s handswere not even visible. In the remaining videos, instructors mostly used theirhands to point or to make emphatic “beat” gestures. They employed symbolicgestures—the type of gesture that is especially helpful in conveying abstractconcepts—in fewer than 10 percent of the videos reviewed.

Symbolic gestures, which are the most valuable for relaying abstract information, are some of the least seen in online digital pedagogy. Slightly more frequent are "beat" gestures that are used for emphatic emphasis, while in the majority of studied online instructional videos the lecturers hands aren't seen on the video at all.

-

A number ofstudies have demonstrated that instructional videos that include gesture producesignificantly more learning for the people who watch them: viewers direct theirgaze more efficiently, pay more attention to essential information, and morereadily transfer what they have learned to new situations. Videos that incorporategesture seem to be especially helpful for those who begin with relatively littleknowledge of the concept being covered; for all learners, the beneficial effect ofgesture appears to be even stronger for video instruction than for live, in-personinstruction.

Gestures can help viewers direct their attention to the most salient and important points in a conversation or a lecture. As a result, learning has been show to be improved in watching lectures with gestures.

Learning using gestures has been shown to be stronger in video presentations over in-person instruction.

-

Cooke often employs a modified form of sign language with her (hearing)students at UMass. By using her hands, Cooke finds, she can accurately capturethe three-dimensional nature of the phenomena she’s explaining.

Can gesturing during (second) language learning help dramatically improve the speed and facility of the second language acquisition by adult learners?

Evidence in language acquisition in children quoted previously in The Extended Mind would indicate yes.

link this related research

-

Such results suggest that the act of gesturing doesn’t just help communicatespatial concepts to others; it also helps the gesturer herself understand theconcepts more fully. Indeed, without gesture as an aid, students may fail tounderstand spatial ideas at all

Could the pedagogy of using gestures to understand "strike and dip" in geology also be applied to using the right hand rule in better understanding electricity and magnetism? Would research on this idea show similar results as in geology? This could be an interesting way of testing this result in another area.

-

“penetrative thinking.” This is the capacity to visualize and reason about theinterior of a three-dimensional object from what can be seen on its surface—acritical skill in geology, and one with which many students struggle.

Penetrative thinking is the ability to abstractly consider and internally visualize or theorize about the inside of a three dimensional object based on what can be seen on its surface.

Penetrative thinking can be useful in areas like geology and anatomy.

Improvements in penetrative thinking can be exercised, encouraged, and improved by using gestures.

-

Students learning about geology for the first time can also benefit from usinggesture.

Geology is a solid example of an area in which gesture can be used in teaching the subject, by using the hands to indicate the movements of one mass against another.

-

Research shows that people who are asked to write on complex topics,instead of being allowed to talk and gesture about them, end up reasoning lessastutely and drawing fewer inferences.

Should active reading, thinking, and annotating also include making gestures as a means of providing more clear reasoning, and drawing better inferences from one's material?

Would gestural movements with a hand or physical writing be helpful in annotation over digital annotation using typing as an input? Is this related to the anecdotal evidence/research of handwriting being a better method of note taking over typing?

Could products like Hypothes.is or Diigo benefit from the use of digital pens on screens as a means of improving learning over using a mouse and a keyboard to highlight and annotate?

-

Gesture encourages experimentation.”

—Susan Goldin-Meadow

Can teachers encourage gesture as a means of helping their students learn? How might this be done?

-

Goldin-Meadow has found, learners who produce such speech-gesture mismatches are especially receptive to instruction—ready to absorb andapply the correct knowledge, should a parent or teacher supply it.

gesture mismatch indicates reception to instruction

People can demonstrate a mismatch between what they gesture and what they say. This mismatch occurs both during development as well as in adulthood and can often be seen during problem solving. Susan Goldin-Meadow had research that indicates that learners who demonstrate this sort of gesture mismatch are more receptive to instruction.

Is there a way to encourage or force gesture mismatch as a means of improving pedagogy?

Tags

- beat gestures

- mnemonic techniques

- understanding

- vocabulary

- Manuela Macedonia

- anatomy

- language pedagogy

- handwriting

- teaching styles

- sketchnotes

- gesture mismatch

- questions

- gender bias

- active reading

- performances

- digital pedagogy

- symbolic gestures

- proprioceptive memory

- acting

- proprioception

- psychology

- auditory memory

- mathematics

- cognitive load

- quotes

- Cornell notes

- annotations

- lip reading

- intentional gestures

- thinking

- language acquisition

- experimentation

- sign language

- pedagogy

- visualizations

- long-term memory

- replicating results

- open questions

- penetrative thinking

- external scaffolding

- mathematics definitions

- gender disparities

- electromagnetic theory

- Welsh

- associative memory

- handwriting vs. typing

- gestures

- video versus in-person instruction

- child development

- geology

- pedagogical devices

- visual memory

- learning techniques

- spatial thinking

- examples

- learning methods

- Diigo

- note taking methods

- Hypothes.is

- tools for thought

Annotators

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8WGozqgMuc

Short review of his book Small Teaching. It apparently presents some small implementable tidbits to make incremental change easier to implement.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Feb 2022

-

insertlearning.com insertlearning.com

-

Referred to me by Mark Grabe.

-

-

learningaloud.com learningaloud.com

-

https://learningaloud.com/blog/2020/08/08/designing-instruction-using-layering-services/

Mark Grabe categorizes some digital pedagogy tools in terms of how they function structurally.

- two servers/independent content

- one server, independent purchased content

- one company offering both a layering capability and content

- user can upload content

-

-

www.unige.ch www.unige.ch

-

The basic approach is in line with Krashen's influential Theory of Input, suggesting that language learning proceeds most successfully when learners are presented with interesting and comprehensible L2 material in a low-anxiety situation.

Stephen Krashen's Theory of Input indicates that language learning is most successful when learners are presented with interesting and comprehensible material in low-anxiety situations.

-

-

thinkzone.wlonk.com thinkzone.wlonk.com

-

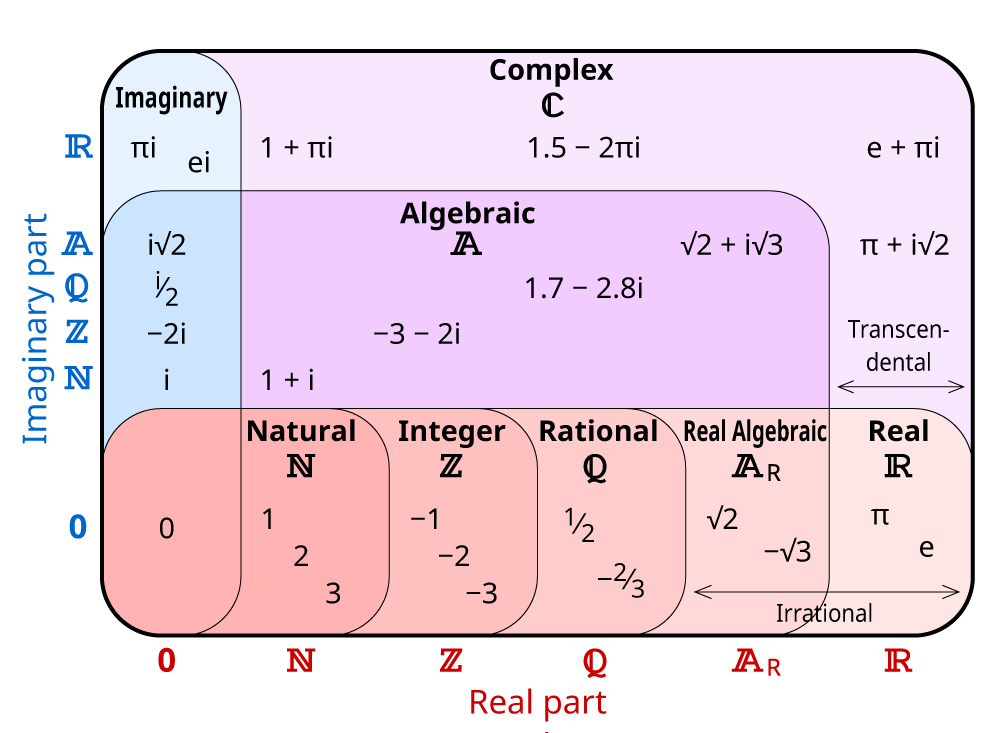

https://thinkzone.wlonk.com/Numbers/NumberSets.htm

A relatively clear explanation of the types of numbers and their properties.

I particularly like this diagram:

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Read for Understanding

Ahrens goes through a variety of research on teaching and learning as they relate to active reading, escaping cognitive biases, creating understanding, progressive summarization, elaboration, revision, etc. as a means of showing and summarizing how these all dovetail nicely into a fruitful long term practice of using a slip box as a note taking method. This makes the zettelkasten not only a great conversation partner but an active teaching and learning partner as well. (Though he doesn't mention the first part in this chapter or make this last part explicit.)

-

Working with the slip-box, therefore, doesn’t mean storinginformation in there instead of in your head, i.e. not learning. On thecontrary, it facilitates real, long-term learning

The forms of thinking, writing, and elaboration that go into creating permanent notes for a slip box are natural means of facilitating actual, long-term learning.

-

Even without any feedback, we will be better off ifwe try to remember something ourselves (Jang et al. 2012).

-

If we put effort into the attempt of retrievinginformation, we are much more likely to remember it in the long run,even if we fail to retrieve it without help in the end (Roediger andKarpicke 2006)

-

When we try to answer a question before we know how to, we willlater remember the answer better, even if our attempt failed (Arnoldand McDermott 2013)

-

“Manipulations such as variation, spacing, introducing contextualinterference, and using tests, rather than presentations, as learningevents, all share the property that they appear during the learningprocess to impede learning, but they then often enhance learning asmeasured by post-training tests of retention and transfer. Conversely,manipulations such as keeping conditions constant and predictable andmassing trials on a given task often appear to enhance the rate oflearning during instruction or training, but then typically fail to supportlong-term retention and transfer” (Bjork, 2011, 8).

This is a surprising effect for teaching and learning, and if true, how can it be best leveraged. Worth reading up on and testing this effect.

Indeed humans do seem built for categorizing and creating taxonomies and hierarchies, and perhaps allowing this talent to do some of the work may be the best way to learn not only in the short term, but over longer term evolutionary periods?

-

Bjork, Robert A. 2011. “On the Symbiosis of Remembering,Forgetting and Learning.” In Successful Remembering andSuccessful Forgetting: a Festschrift in Honor of Robert A. Bjork,edited by Aaron S. Benjamin, 1–22. New York, NY: PsychologyPress.

-

Learning requires effort, because we have to think to understandand we need to actively retrieve old knowledge to convince ourbrains to connect it with new ideas as cues. To understand howgroundbreaking this idea is, it helps to remember how much effortteachers still put into the attempt to make learning easier for theirstudents by prearranging information, sorting it into modules,categories and themes. By doing that, they achieve the opposite ofwhat they intend to do. They make it harder for the student to learnbecause they set everything up for reviewing, taking away theopportunity to build meaningful connections and to make sense ofsomething by translating it into one’s own language. It is like fastfood: It is neither nutritious nor very enjoyable, it is just convenient

Some of the effort that teachers put into their educational resources in an attempt to make learning faster and more efficient is actually taking away the actual learning opportunities of the students to sort, arrange, and make meaningful connections between the knowledge and to their own prior knowledge bases.

In mathematics, rather than showing a handful of methods for solving a problem, the teacher might help students to explore those problem solving spaces first and then assist them into creating these algorithms. I can't help but think about Inventional Geometry by William George Spencer that is structured this way. The teacher has created a broader super-structure of problems, but leaves it largely to the student to do the majority of the work.

Tags

- counterintuitive pedagogy

- understanding

- elaboration

- feedback loops

- William George Spencer

- pedagogy

- cognitive bias

- learning

- taxonomies

- zettelkasten

- teaching

- Inventional Geometry

- associative memory

- memory

- pedagogical devices

- psychology

- forgetting

- zettelkasten design

- putting in the work

- evolution of order

- hierarchies

- quotes

- want to read

- progressive summarization

- tools for thought

- human resources

Annotators

-

-

wvupressonline.com wvupressonline.com

-

eBook 978-1-952271-05-2 $24.99

because, of course, you've got to read the digital version of this book!

-

-

threadreaderapp.com threadreaderapp.com

- Jan 2022

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

Books can indeed be dangerous. Until “Close Quarters,” I believed stories had the power to save me. That novel taught me that stories also had the power to destroy me. I was driven to become a writer because of the complex power of stories. They are not inert tools of pedagogy. They are mind-changing, world-changing.

—Viet Thanh Nguyen

-

-

eleanorkonik.com eleanorkonik.com

-

https://eleanorkonik.com/the-difficulties-of-teaching-notetaking/

A fascinating take on why we don't teach study skills and note taking the way they had traditionally been done in the past. What we're teaching and teaching toward has changed dramatically.

-

The problem in my experience isn’t that teachers don’t teach enough notetaking systems… the problem is we don’t have good tools to ramp up the difficulty of an individual student’s education at an appropriate rate.

How can we dramatically increase the complexity of our teaching both knowledge and skills so that students need solid note taking skills earlier in their education.

-

-

-

culture that taught to learn by rote and a culture that taught to forget instead

Pedagogical cultrues:

- cultures taught orally

- cultures taught to remember

- cultures taught to learn by rote

- cultures taught to forget

Is there a (linear) progression? How do they differ? How are they they same? Is there a 1-1 process that allows them to be equivalence classes?

-

- Dec 2021

-

crookedtimber.org crookedtimber.org

-

Law One: The more reading you assign, the less the students will read. Law Two: The more you talk in class, the less the students will read.

Two Iron Laws of College Reading https://crookedtimber.org/2021/12/22/two-iron-laws-of-college-reading/

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

- Nov 2021

-

www.slideshare.net www.slideshare.net

-