Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

The Reviewer structured their review such that their first two recommendations specifically concerned the two major weaknesses they viewed in the initial submission. For clarity and concision, we have copied their recommendations to be placed immediately following their corresponding points on weaknesses.

Strengths:

Studying prediction error from the lens of network connectivity provides new insights into predictive coding frameworks. The combination of various independent datasets to tackle the question adds strength, including two well-powered fMRI task datasets, resting-state fMRI interpreted in relation to behavioral measures, as well as EEG-fMRI.

Weaknesses:

Major:

(R1.1) Lack of multiple comparisons correction for edge-wise contrast:

The analysis of connectivity differences across three levels of prediction error was conducted separately for approximately 22,000 edges (derived from 210 regions), yet no correction for multiple comparisons appears to have been applied. Then, modularity was applied to the top 5% of these edges. I do not believe that this approach is viable without correction. It does not help that a completely separate approach using SVMs was FDR-corrected for 210 regions.

[Later recommendation] Regarding the first major point: To address the issue of multiple comparisons in the edge-wise connectivity analysis, I recommend using the Network-Based Statistic (NBS; Zalesky et al., 2010). NBS is well-suited for identifying clusters (analogous to modules) of edges that show statistically significant differences across the three prediction error levels, while appropriately correcting for multiple comparisons.

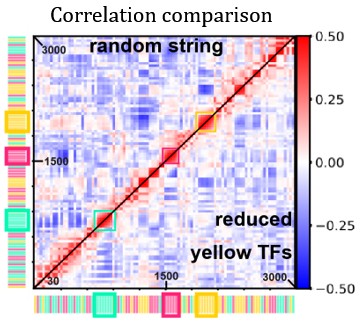

Thank you for bringing this up. We acknowledge that our modularity analysis does not evaluate statistical significance. Originally, the modularity analysis was meant to provide a connectome-wide summary of the connectivity effects, whereas the classification-based analysis was meant to address the need for statistical significance testing. However, as the reviewer points out, it would be better if significance were tested in a manner more analogous to the reported modules. As they suggest, we updated the Supplemental Materials (SM) to include the results of Network-Based Statistic analysis (SM p. 1-2):

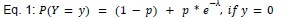

“(2.1) Network-Based Statistic

Here, we evaluate whether PE significantly impacts connectivity at the network level using the Network-Based Statistic (NBS) approach.[1] NBS relied on the same regression data generated for the main-text analysis, whereby a regression is performed examining the effect of PE (Low = –1, Medium = 0, High = +1) on connectivity for each edge. This was done across the connectome, and for each edge, a z-score was computed. For NBS, we thresholded edges to |Z| > 3.0, which yielded one large network cluster, shown in Figure S3. The size of the cluster – i.e., number of edges – was significant (p < .05) per a permutation-test using 1,000 random shuffles of the condition data for each participant, as is standard.[1] These results demonstrate that the networklevel effects of PE on connectivity are significant. The main-text modularity analysis converts this large cluster into four modules, which are more interpretable and open the door to further analyses”.

We updated the Results to mention these findings before describing the modularity analysis (p. 8-9):

“After demonstrating that PE significantly influences brain-wide connectivity using Network-Based Statistic analysis (Supplemental Materials 2.1), we conducted a modularity analysis to study how specific groups of edges are all sensitive to high/low-PE information.”

(R1.2) Lack of spatial information in EEG:

The EEG data were not source-localized, and no connectivity analysis was performed. Instead, power fluctuations were averaged across a predefined set of electrodes based on a single prior study (reference 27), as well as across a broader set of electrodes. While the study correlates these EEG power fluctuations with fMRI network connectivity over time, such temporal correlations do not establish that the EEG oscillations originate from the corresponding network regions. For instance, the observed fronto-central theta power increases could plausibly originate from the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), as consistently reported in the literature, rather than from a distributed network. The spatially agnostic nature of the EEG-fMRI correlation approach used here does not support interpretations tied to specific dorsal-ventral or anterior-posterior networks. Nonetheless, such interpretations are made throughout the manuscript, which overextends the conclusions that can be drawn from the data.

[Later recommendation] Regarding the second major point: I suggest either adopting a source-localized EEG approach to assess electrophysiological connectivity or revising all related sections to avoid implying spatial specificity or direct correspondence with fMRI-derived networks. The current approach, which relies on electrode-level power fluctuations, does not support claims about the spatial origin of EEG signals or their alignment with specific connectivity networks.

We thank the reviewer for this important point, which allows us to clarify the specific and distinct contributions of each imaging modality in our study. Our primary goal for Study 3 was to leverage the high temporal resolution of EEG to identify the characteristic frequency at which the fMRI-defined global connectivity states fluctuate. The study was not designed to infer the spatial origin of these EEG signals, a task for which fMRI is better suited and which we addressed in Studies 1 and 2.

As the reviewer points out, fronto-central theta is generally associated with the dACC. We agree with this point entirely. We suspect that there is some process linking dACC activation to the identified network fluctuations – some type of relationship that does not manifest in our dynamic functional connectivity analyses – although this is only a hypothesis and one that is beyond the present scope.

We updated the Discussion to mention these points and acknowledge the ambiguity regarding the correlation between network fluctuation amplitude (fMRI) and Delta/Theta power (EEG) (p. 24):

“We specifically interpret the fMRI-EEG correlation as reflecting fluctuation speed because we correlated EEG oscillatory power with the fluctuation amplitude computed from fMRI data. Simply correlating EEG power with the average connectivity or the signed difference between posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity yields null results (Supplemental Materials 6), suggesting that this is a very particular association, and viewing it as capturing fluctuation amplitude provides a parsimonious explanation. Yet, this correlation may be interpreted in other ways. For example, resting-state Theta is also a signature of drowsiness,[2] which may correlate with PE processing, but perhaps should be understood as some other mechanism. Additionally, Theta is widely seen as a sign of dorsal anterior cingulate cortex activity,3 and it is unclear how to reconcile this with our claims about network fluctuations. Nonetheless, as we show with simulations (Supplemental Materials 5), a correlation between slow fMRI network fluctuations and fast EEG Delta/Theta oscillations is also consistent with a common global neural process oscillating rapidly and eliciting both measures.”

Regarding source-localization, several papers have described known limitations of this strategy for drawing precise anatomical inferences,[4–6] and this seems unnecessary given that our fMRI analyses already provide more robust anatomical precision. We intentionally used EEG in our study for what it measures most robustly: millisecond-level temporal dynamics.

(R1.2a)Examples of problematic language include:

Line 134: "detection of network oscillations at fast speeds" - the current EEG approach does not measure networks.

This is an important issue. We acknowledge that our EEG approach does not directly measure fMRI-defined networks. Our claim is inferential, designed to estimate the temporal dynamics of the large-scale fMRI patterns we identified. The correlation between our fMRI-derived fluctuation amplitude (|PA – VD|) and 3-6 Hz EEG power provides suggestive evidence that the transitions between these network states occur at this frequency, rather than being a direct measurement of network oscillations.

To support the validity of this inference, we performed two key analyses (now in Supplemental Materials). First, a simulation study provides a proof-of-concept, confirming our method can recover the frequency of a fast underlying oscillator from slow fMRI and fast EEG data. Second, a specificity analysis shows the EEG correlation is unique to our measure of fluctuation amplitude and not to simpler measures like overall connectivity strength. These analyses demonstrate that our interpretation is more plausible than alternative explanations.

Overall, we have revised the manuscript to be more conservative in the language employed, such as presenting alternative explanations to the interpretations put forth based on correlative/observational evidence (e.g., our modifications above described in our response to comment R1.2). In addition, we have made changes throughout the report to state the issues related to reverse inference more explicitly and to better communicate that the evidence is suggestive – please see our numerous changes described in our response to comment R3.1. For the statement that the reviewer specifically mentioned here, we revised it to be more cautious (p. 7):

“Although such speed outpaces the temporal resolution of fMRI, correlating fluctuations in dynamic connectivity measured from fMRI data with EEG oscillations can provide an estimate of the fluctuations’ speed. This interpretation of a correlation again runs up against issues related to reverse inference but would nonetheless serve as initial suggestive evidence that spontaneous transitions between network states occur rapidly.”

(R1.2b) Line 148: "whether fluctuations between high- and low-PE networks occur sufficiently fast" - this implies spatial localization to networks that is not supported by the EEG analysis.

Building on our changes described in our immediately prior response, we adjusted our text here to say our analyses searched for evidence consistent with the idea that the network fluctuations occur quickly rather than searching for decisive evidence favoring this idea (p. 7-8):

“Finally, we examined rs-fMRI-EEG data to assess whether we find parallels consistent with the high/low-PE network fluctuations occurring at fast timescales suitable for the type of cognitive operations typically targeted by PE theories.”

(R1.2c) Line 480: "how underlying neural oscillators can produce BOLD and EEG measurements" - no evidence is provided that the same neural sources underlie both modalities.

As described above, these claims are based on the simulation study demonstrating that this is a possibility, and we have revised the manuscript overall to be clearer that this is our interpretation while providing alternative explanations.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Strengths:

Clearly, a lot of work and data went into this paper, including 2 task-based fMRI experiments and the resting state data for the same participants, as well as a third EEG-fMRI dataset. Overall, well written with a couple of exceptions on clarity, as per below, and the methodology appears overall sound, with a couple of exceptions listed below that require further justification. It does a good job of acknowledging its own weakness.

Weaknesses:

(R2.1) The paper does a good job of acknowledging its greatest weakness, the fact that it relies heavily on reverse inference, but cannot quite resolve it. As the authors put it, "finding the same networks during a prediction error task and during rest does not mean that the networks' engagement during rest reflects prediction error processing". Again, the authors acknowledge the speculative nature of their claims in the discussion, but given that this is the key claim and essence of the paper, it is hard to see how the evidence is compelling to support that claim.

We thank the reviewer for this comment. We agree that reverse inference is a fundamental challenge and that our central claim requires a particularly high bar of evidence. While no single analysis resolves this issue, our goal was to build a cumulative case that is compelling by converging on the same conclusion from multiple, independent lines of evidence.

For our investigation, we initially established a task-general signature of prediction error (PE). By showing the same neural pattern represents PE in different contexts, we constrain the reverse inference, making it less likely that our findings are a task-specific artifact and more likely that they reflect the core, underlying process of PE. Building on this, our most compelling evidence comes from linking task and rest at the individual level. We didn't just find the same general network at rest; we showed that an individual’s unique anatomical pattern of PE-related connectivity during the task specifically predicts their own brain's fluctuation patterns at rest. This highly specific, person-by-person correspondence provides a direct bridge between an individual's task-evoked PE processing and their intrinsic, resting-state dynamics. Furthermore, these resting-state fluctuations correlate specifically with the 3-6 Hz theta rhythm—a well-established neural marker for PE.

While reverse inference remains a fundamental limitation for many studies on resting-state cognition, the aspects mentioned above, we believe, provide suggestive evidence, favoring our PE interpretation. Nonetheless, we have made changes throughout the manuscript to be more conservative in the language we use to describe our results, to make it clear what claims are based on correlative/observational evidence, and to put forth alternative explanations for the identified effects. Please find our numerous changes detailed in our response to comment R3.1.

(R2.2) Given how uncontrolled cognition is during "resting-state" experiments, the parallel made with prediction errors elicited during a task designed for that effect is a little difficult to make. How often are people really surprised when their brains are "at rest", likely replaying a previously experienced event or planning future actions under their control? It seems to be more likely a very low prediction error scenario, if at all surprising.

We (and some others) take a broad interpretation of PE and believe it is often more intuitive to think about PE minimization in terms of uncertainty rather than “surprise”; the word “surprise” usually implies a sudden emotive reaction from the violation of expectations, which is not useful here.

When planning future actions, each step of the plan is spurred by the uncertainty of what is the appropriate action given the scenario set up by prior steps. Each planned step erases some of that uncertainty. For example, you may be mentally simulating a conversation, what you will say, and what another person will say. Each step of this creates uncertainty of “what is the appropriate response?” Each reasoning step addresses contingencies. While planning, you may also uncover more obvious forms of uncertainty, sparking memory retrieval to finish it. A resting-state participant may think to cook a frozen pizza when they arrive home, but be uncertain about whether they have any frozen pizzas left, prompting episodic memory retrieval to address this uncertainty. We argue that every planning step or memory retrieval can be productively understood as being sparked by uncertainty/surprise (PE), and the subsequent cognitive response minimizes this uncertainty.

We updated the Introduction to include a paragraph near the start providing this explanation (p. 3-4):

“PE minimization may broadly coordinate brain functions of all sorts, including abstract cognitive functions. This includes the types of cognitive processes at play even in the absence of stimuli (e.g., while daydreaming). While it may seem counterintuitive to associate this type of cognition with PE – a concept often tied to external surprises – it has been proposed that the brain's internal generative model is continuously active.[12–14] Spontaneous thought, such as planning a future event or replaying a memory, is not a passive, low-PE process. Rather, it can be seen as a dynamic cycle of generating and resolving internal uncertainty. While daydreaming, you may be reminded of a past conversation, where you wish you had said something different. This situation contains uncertainty about what would have been the best thing to say. Wondering about what you wish you said can be viewed as resolving this uncertainty, in principle, forming a plan if the same situation ever arises again in the future. Each iteration of the simulated conversation repeatedly sparks and then resolves this type of uncertainty.”

(R2.3)The quantitative comparison between networks under task and rest was done on a small subset of the ROIs rather than on the full network - why? Noting how small the correlation between task and rest is (r=0.021) and that's only for part of the networks, the evidence is a little tenuous. Running the analysis for the full networks could strengthen the argument.

We thank the reviewer for this opportunity to clarify our method. A single correlation between the full, aggregated networks would be conceptually misaligned with what we aimed to assess. To test for a personspecific anatomical correspondence, it is necessary to examine the link between task and rest at a granular level. We therefore asked whether the specific parts of an individual's network most responsive to PE during the task are the same parts that show the strongest fluctuations at rest. Our analysis, performed iteratively across all 3,432 possible ROI subsets, was designed specifically to answer this question, which would be obscured by an aggregated network measure.

We appreciate the reviewer's concern about the modest effect size (r = .021). However, this must be contextualized, as the short task scan has very low reliability (.08), which imposes a severe statistical ceiling on any possible task-rest correlation. Finding a highly significant effect (p < .001) in the face of such noisy data, therefore, provides robust evidence for a genuine task-rest correspondence.

We updated the Discussion to discuss this point (p. 22-23):

“A key finding supporting our interpretation is the significant link between individual differences in task-evoked PE responses and resting-state fluctuations. One might initially view the effect size of this correspondence (r = .021) as modest. However, this interpretation must be contextualized by the considerable measurement noise inherent in short task-fMRI scans; the split-half reliability of the task contrast was only .08. This low reliability imposes a severe statistical ceiling on any possible task-rest correlation. Therefore, detecting a highly significant (p < .001) relationship despite this constraint provides robust evidence for a genuine link. Furthermore, our analytical approach, which iteratively examined thousands of ROI subsets rather than one aggregated network, was intentionally granular. The goal was not simply to correlate two global measures, but to test for a personspecific anatomical correspondence – that is, whether the specific parts of an individual's network most sensitive to PE during the task are the same parts that fluctuate most strongly at rest. An aggregate analysis would obscure this critical spatial specificity. Taken together, this granular analysis provides compelling evidence for an anatomically consistent fingerprint of PE processing that bridges task-evoked activity and spontaneous restingstate dynamics, strengthening our central claim.”

(R2.4) Looking at the results in Figure 2C, the four-quadrant description of the networks labelled for low and high PE appears a little simplistic. The authors state that this four-quadrant description omits some ROIs as motivated by prior knowledge. This would benefit from a more comprehensive justification.Which ROIs are excluded, and what is the evidence for exclusion?

Our four-quadrant model is a principled simplification designed to distill the dominant, large-scale connectivity patterns from the complex modularity results. This approach focuses on coherent, well-documented anatomical streams while setting aside a few anatomically distant and disjoint ROIs that were less central to the main modules. This heuristic additionally unlocks more robust and novel analyses.

The two low-PE posterior-anterior (PA) pathways are grounded in canonical processing streams. (i) The OCATL connection mirrors the ventral visual stream (the “what” pathway), which is fundamental for object recognition and is upregulated during the smooth processing of expected stimuli. (ii) The IPL-LPFC connection represents a core axis of the dorsal attention stream and the Fronto-Parietal Control Network (FPCN), reflecting the maintenance of top-down cognitive control when information is predictable; the IPL-LPFC module excludes ROIs in the middle temporal gyrus, which are often associated with the FPCN but are not covered here.

In contrast, the two high-PE ventral-dorsal (VD) pathways reflect processes for resolving surprise and conflict. (i) The OC-IPL connection is a classic signature of attentional reorienting, where unexpected sensory input (high PE) triggers a necessary shift in attention; the OC-IPL module excludes some ROIs that are anterior to the occipital lobe and enter the fusiform gyrus and inferior temporal lobe. (ii) The ATL-LPFC connection aligns with mechanisms for semantic re-evaluation, engaging prefrontal control regions to update a mental model in the face of incongruent information.

Beyond its functional/anatomical grounding, this simplification provides powerful methodological and statistical advantages. It establishes a symmetrical framework that makes our dynamic connectivity analyses tractable, such as our “cube” analysis of state transitions, which required overlapping modules. Critically, this model also offers a statistical safeguard. By ensuring each quadrant contributes to both low- and high-PE connectivity patterns, we eliminate confounds like region-specific signal variance or global connectivity. This design choice isolates the phenomenon to the pattern of connectivity itself (posterior-anterior vs. ventral-dorsal), making our interpretation more robust.

We updated the end of the Study 1A results (p. 10-11):

“Some ROIs appear in Figure 2C but are excluded from the four targeted quadrants (Figures 2C & 2D) – e.g., posterior inferior temporal lobe and fusiform ROIs are excluded from the OC-IPL module, and middle temporal gyrus ROIs are excluded from the IPL-LPFC modules. These exclusions, in favor of a four-quadrant interpretation, are motivated by existing knowledge of prominent structural pathways among these quadrants. This interpretation is also supported by classifier-based analyses showing connectivity within each quadrant is significantly influenced by PE (Supplemental Materials 2.2), along with analyses of single-region activity showing that these areas also respond to PE independently (Supplemental Materials 3). Hence, we proceeded with further analyses of these quadrants’ connections, which summarize PE’s global brain effects.

“This four-quadrant setup also imparts analytical benefits. First, this simplified structure may better generalize across PE tasks, and Study 1B would aim to replicate these results with a different design. Second, the four quadrants mean that each ROI contributes to both the posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal modules, which would benefit later analyses and rules out confounds such as PE eliciting increased/decreased connectivity between an ROI and the rest of the brain. An additional, less key benefit is that this setup allows more easily evaluating whether the same phenomena arise using a different atlas (Supplemental Materials Y).”

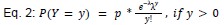

(R2.5) The EEG-fMRI analysis claiming 3-6Hz fluctuations for PE is hard to reconcile with the fact that fMRI captures activity that is a lot slower, while some PEs are as fast as 150 ms. The discussion acknowledges this but doesn't seem to resolve it - would benefit from a more comprehensive argument.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point, which allows us to clarify the logic of our multimodal analysis. Our analysis does not claim that the fMRI BOLD signal itself oscillates at 3-6 Hz. Instead, it is based on the principle that the intensity of a fast neural process can be reflected in the magnitude of the slow BOLD response. It’s akin to using a long-exposure photograph to capture a fast-moving object; while the individual movements are blurred, the intensity of the blur in the photo serves as a proxy for the intensity of the underlying motion. In our case, the magnitude of the fMRI network difference (|PA – VD|) acts as the "blur," reflecting the intensity of the rapid fluctuations between states within that time window.

Following this logic, we correlated this slow-moving fMRI metric with the power of the fast EEG rhythms, which reflects their amplitude. To bridge the different timescales, we averaged the EEG power over each fMRI time window and convolved it with the standard hemodynamic response function (HRF) – a crucial step to align the timing of the neural and metabolic signals. The resulting significant correlation specifically in the 3-6 Hz band demonstrates that when this rhythm is stronger, the fMRI data shows a greater divergence between network states. This allows us to infer the characteristic frequency of the underlying neural fluctuations without directly measuring them at that speed with fMRI, thus reconciling the two timescales.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Bogdan et al. present an intriguing and timely investigation into the intrinsic dynamics of prediction error (PE)-related brain states. The manuscript is grounded in an intuitive and compelling theoretical idea: that the brain alternates between high and low PE states even at rest, potentially reflecting an intrinsic drive toward predictive minimization. The authors employ a creative analytic framework combining different prediction tasks and imaging modalities. They shared open code, which will be valuable for future work.

(R3.1) Consistency in Theoretical Framing

The title, abstract, and introduction suggest inconsistent theoretical goals of the study.

The title suggests that the goal is to test whether there are intrinsic fluctuations in high and low PE states at rest. The abstract and introduction suggest that the goal is to test whether the brain intrinsically minimizes PE and whether this minimization recruits global brain networks. My comments here are that a) these are fundamentally different claims, and b) both are challenging to falsify. For one, task-like recurrence of PE states during resting might reflect the wiring and geometry of the functional organization of the brain emerging from neurobiological constraints or developmental processes (e.g., experience), but showing that mirroring exists because of the need to minimize PE requires establishing a robust relationship with behavior or showing a causal effect (e.g., that interrupting intrinsic PE state fluctuations affects prediction).

The global PE hypothesis-"PE minimization is a principle that broadly coordinates brain functions of all sorts, including abstract cognitive functions"-is more suitable for discussion rather than the main claim in the abstract, introduction, and all throughout the paper.

Given the above, I recommend that the authors clarify and align their core theoretical goals across the title, abstract, introduction, and results. If the focus is on identifying fluctuations that resemble taskdefined PE states at rest, the language should reflect that more narrowly, and save broader claims about global PE minimization for the discussion. This hypothesis also needs to be contextualized within prior work. I'd like to see if there is similar evidence in the literature using animal models.

Thank you for bringing up this issue. We have made changes throughout the paper to address these points. First, we have omitted reference to a “global PE hypothesis” from the Abstract and Introduction, in favor of structuring the Introduction in terms of a falsifiable question (p. 4):

“We pursued this goal using three studies (Figure 1) that collectively targeted a specific question: Do the taskdefined connectivity signatures of high vs. low PE also recur during rest, and if so, how does the brain transition between exhibiting high/low signatures?”

We made changes later in the Introduction to clarify that the investigation is based on correlative evidence and requires interpretations that may be debated (p. 5-7):

“Although this does not entirely address the reverse inference dilemma and can only produce correlative evidence, the present research nonetheless investigates these widely speculated upon PE ideas more directly than any prior work.

Although such speed outpaces the temporal resolution of fMRI, correlating fluctuations in dynamic connectivity measured from fMRI data with EEG oscillations can provide an estimate of the fluctuations’ speed. This interpretation of a correlation again runs up against issues related to reverse inference but would nonetheless serve as initial suggestive evidence that spontaneous transitions between network states occur rapidly.

Second, we examined the recruitment of these networks during rs-fMRI, and although the problems related to reverse inference are impossible to overcome fully, we engage with this issue by linking rs-fMRI data directly to task-fMRI data of the same participants, which can provide suggestive evidence that the same neural mechanisms are at play in both.”

We made changes throughout the Results now better describing the results as consistent with a hypothesis rather than demonstrating it (p. 12-19):

“In other words, we essentially asked whether resting-state participants are sometimes in low PE states and sometimes in high PE states, which would be consistent with spontaneous PE processing in the absence of stimuli.

These emerging states overlap strikingly with the previous task effects of PE, suggesting that rs-fMRI scans exhibit fluctuations that resemble the signatures of low- and high-PE states.

To be clear, this does not entirely dissuade concerns about reverse inference, which would require a type of causal manipulation that is difficult (if not impossible) to perform in a resting state scan. Nonetheless, these results provide further evidence consistent with our interpretation that the resting brain spontaneously fluctuates between high/low PE network states.

These patterns are most consistent with a characteristic timescale near 3–6 Hz for the amplitude of the putative high/low-PE fluctuations. This is notably consistent with established links between PE and Delta/Theta and is further consistent with an interpretation in which these fluctuations relate to PE-related processing during rest.”

We have also made targeted edits to the Discussion to present the findings in a more cautious way, more clearly state what is our interpretation, and provide alternative explanations (p. 19-26):

“The present research conducted task-fMRI, rs-fMRI, and rs-fMRI-EEG studies to clarify whether PE elicits global connectivity effects and whether the signatures of PE processing arise spontaneously during rest. This investigation carries implications for how PE minimization may characterize abstract task-general cognitive processes. […] Although there are different ways to interpret this correlation, it is consistent with high/low PE states generally fluctuating at 3-6 Hz during rest. Below, we discuss these three studies’ findings.

Our rs-fMRI investigation examined whether resting dynamics resemble the task-defined connectivity signatures of high vs. low PE, independent of the type of stimulus encountered. The resting-state analyses indeed found that, even at rest, participants’ brains fluctuated between strong ventral-dorsal connectivity and strong posterior-anterior connectivity, consistent with shifts between states of high and low PE. This conclusion is based on correlative/observational evidence and so may be controversial as it relies on reverse inference.

These patterns resemble global connectivity signatures seen in resting-state participants, and correlations between fMRI and EEG data yield associations, consistent with participants fluctuating between high-PE (ventral-dorsal) and low-PE (posterior-anterior) states at 3-6 Hz. Although definitively testing these ideas is challenging, given that rs-fMRI is defined by the absence of any causal manipulations, our results provide evidence consistent with PE minimization playing a role beyond stimulus process.”

(R3.2) Interpretation of PE-Related Fluctuations at Rest and Its Functional Relevance. It would strengthen the paper to clarify what is meant by "intrinsic" state fluctuations. Intrinsic might mean taskindependent, trait-like, or spontaneously generated. Which do the authors mean here? Is the key prediction that these fluctuations will persist in the absence of a prediction task?

Of the three terms the reviewer mentioned, “spontaneous” and “task-independent” are the most accurate descriptors. We conceptualize these fluctuations as a continuous background process that persists across all facets of cognition, without requiring a task explicitly designed to elicit prediction error – although we, along with other predictive coding papers, would argue that all cognitive tasks are fundamentally rooted in PE mechanisms and thus anything can be seen as a “prediction task” (see our response to comment R2.2 for our changes to the Introduction that provide more intuition for this point). The proposed interactions can be seen as analogous to cortico-basal-thalamic loops, which are engaged across a vast and diverse array of cognitive processes.

The prior submission only used the word “intrinsic” in the title. We have since revised it to “spontaneous,” which is more specific than “intrinsic,” and we believe clearer for a title than “task-independent” (p. 1): “Spontaneous fluctuations in global connectivity reflect transitions between states of high and low prediction error”

We have also made tweaks throughout the manuscript to now use “spontaneously” throughout (it now appears 8 times in the paper).

Regardless of the intrinsic argument, I find it challenging to interpret the results as evidence of PE fluctuations at rest. What the authors show directly is that the degree to which a subset of regions within a PE network discriminates high vs. low PE during task correlates with the magnitude of separation between high and low PE states during rest. While this is an interesting relationship, it does not establish that the resting-state brain spontaneously alternates between high and low PE states, nor that it does so in a functionally meaningful way that is related to behavior. How can we rule out brain dynamics of other processes, such as arousal, that also rise and fall with PE? I understand the authors' intention to address the reverse inference concern by testing whether "a participant's unique connectivity response to PE in the reward-processing task should match their specific patterns of resting-state fluctuation". However, I'm not fully convinced that this analysis establishes the functional role of the identified modules to PE because of the following:

Theoretically, relating the activities of the identified modules directly to behavior would demonstrate a stronger functional role.

(R3.2a) Across participants: Do individuals who exhibit stronger or more distinct PE-related fluctuations at rest also perform better on tasks that require prediction or inference? This could be assessed using the HCP prediction task, though if individual variability is limited (e.g., due to ceiling effects), I would suggest exploring a dataset with a prediction task that has greater behavioral variance.

This is a good idea, but unfortunately difficult to test with our present data. The HCP gambling task used in our study was not designed to measure individual differences in prediction or inference and likely suffers from ceiling effects. Because the task outcomes are predetermined and not linked to participants' choices, there is very little meaningful behavioral variance in performance to correlate with our resting-state fluctuation measure.

While we agree that exploring a different dataset with a more suitable task would be ideal, given the scope of the existing manuscript, this seems like it would be too much. Although these results would be informative, they would ultimately still not be a panacea for the reverse inference issues.

Or even more broadly, does this variability in resting state PE state fluctuations predict general cognitive abilities like WM and attention (which the HCP dataset also provides)? I appreciate the inclusion of the win-loss control, and I can see the intention to address specificity. This would test whether PE state fluctuations reflect something about general cognition, but also above and beyond these attentional or WM processes that we know are fluctuating.

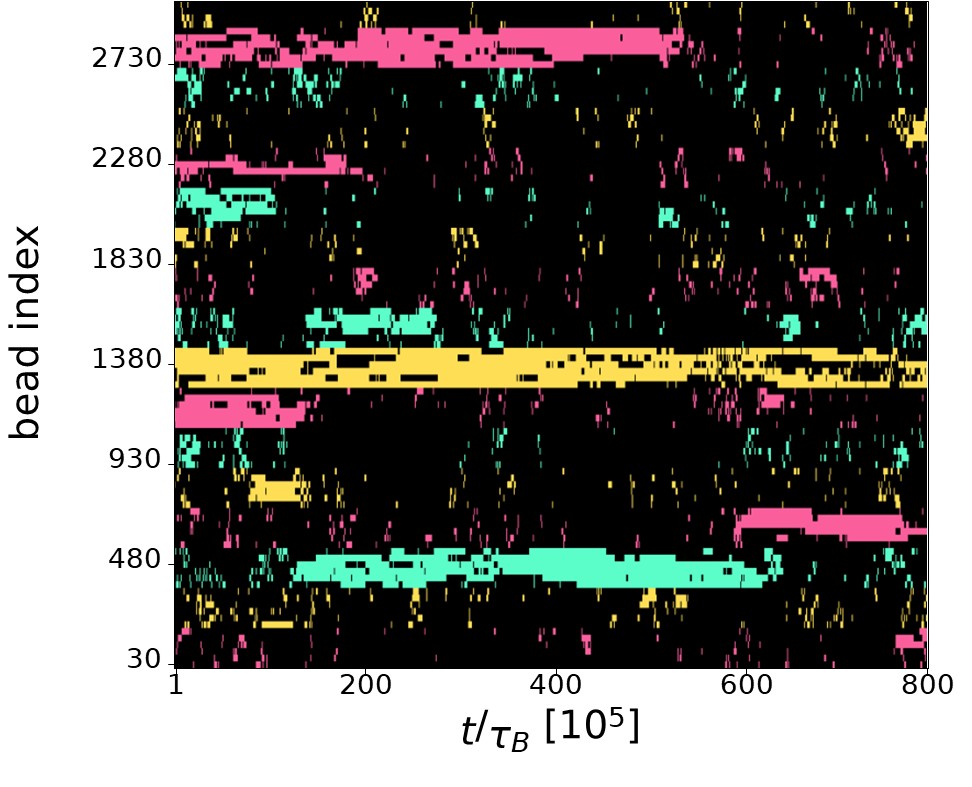

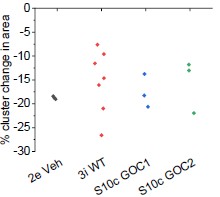

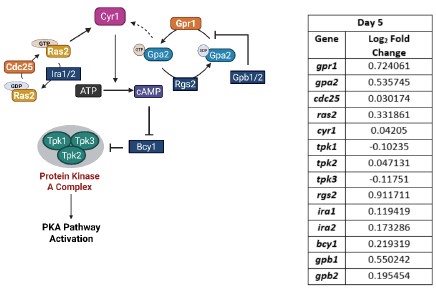

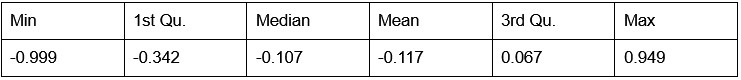

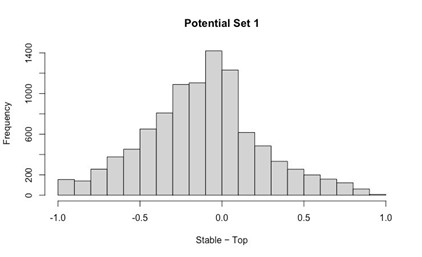

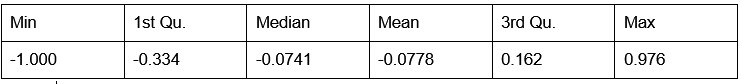

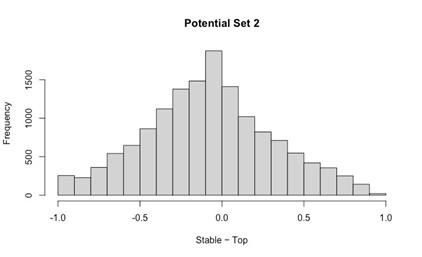

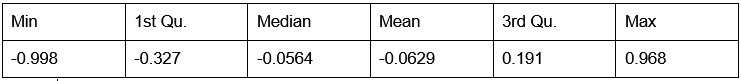

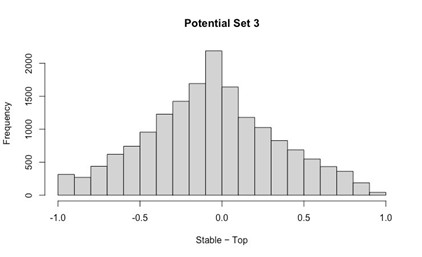

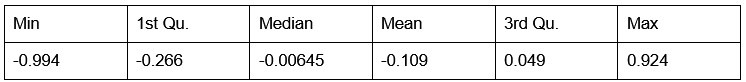

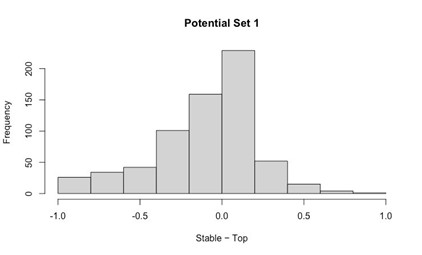

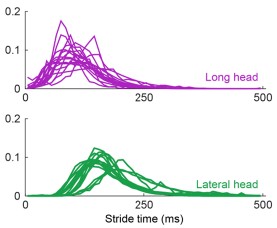

This is a helpful suggestion, motivating new analyses: We measured the degree of resting-state fluctuation amplitude across participants and correlated it with the different individual differences measures provided with the HCP data (e.g., measures of WM performance). We computed each participant’s fluctuation amplitude measure as the average absolute difference between posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity; this is the average of the TR-by-TR fMRI amplitude measure from Study 3. We correlated this individual difference score with all of the ~200 individual difference measures provided with the HCP dataset (e.g., measures of intelligence or personality). We measured the Spearman correlation between mean fluctuation amplitude with each of those ~200 measures, while correcting for multiple hypotheses using the False Discovery Rate approach.[18]

We found a robust negative association with age, where older participants tend to display weaker fluctuations (r = -.16, p < .001). We additionally find a positive association with the age-adjusted score on the picture sequence task (r = .12, p<sub>corrected</sub> = .03) and a negative association with performance in the card sort task (r = -.12, p<sub>corrected</sub> = 046). It is unclear how to interpret these associations, without being speculative, given that fluctuation amplitude shows one positive association with performance and one negative association, albeit across entirely different tasks. We have added these correlation results as Supplemental Materials 8 (SM p. 11):

“(8) Behavioral differences related to fluctuation amplitude

To investigate whether individual differences in the magnitude of resting-state PE-state fluctuations predict general cognitive abilities, we correlated our resting-state fluctuation measure with the cognitive and demographic variables provided in the HCP dataset.

(8.1) Methods

For each of the 1,000 participants, we calculated a single fluctuation amplitude score. This score was defined as the average absolute difference between the time-varying posterior-anterior (PA) and ventral-dorsal (VD) connectivity during the resting-state fMRI scan (the average of the TR-by-TR measure used for Study 3). We then computed the Spearman correlation between this score and each of the approximately 200 individual difference measures provided in the HCP dataset. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach.

(8.2) Results

The correlations revealed a robust negative association between fluctuation amplitude and age, indicating that older participants tended to display weaker fluctuations (r = -.16, p<sub>corrected</sub> < .001). After correction, two significant correlations with cognitive performance emerged: (i) a positive association with the age-adjusted score on the Picture Sequence Memory Test (r = .12, p<sub>corrected</sub> = .03), (ii) a negative association with performance on the Card Sort Task (r = -.12, p<sub>corrected</sub> = .046). As greater fluctuation amplitude is linked to better performance on one task but worse performance on another, it is unclear how to interpret these findings.”

We updated the main text Methods to direct readers to this content (p. 39-40):

“(4.4.3) Links between network fluctuations and behavior

We considered whether the extent of PE-related network expression states during resting-state is behaviorally relevant. We specifically investigated whether individual differences in the overall magnitude of resting-state fluctuations could predict individual difference measures, provided with the HCP dataset. This yielded a significant association with age, whereby older participants tended to display weaker fluctuations. However, associations with cognitive measures were limited. A full description of these analyses is provided in Supplemental Materials 8.”

(R3.2b) Within participants: Do momentary increases in PE-network expression during tasks relate to better or faster prediction? In other words, is there evidence that stronger expression of PE-related states is associated with better behavioral outcomes?

This is a good question that probes the direct behavioral relevance of these network states on a trial-by-trial basis. We agree with the reviewer's intuition; in principle, one would expect a stronger expression of the low-PE network state on trials where a participant correctly and quickly gives a high likelihood rating to a predictable stimulus.

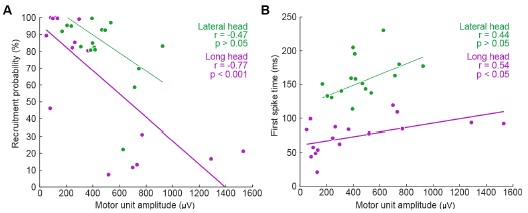

Following this suggestion, we performed a new analysis in Study 1A to test this. We found that while network expression was indeed linked to participants’ likelihood ratings: higher likelihood ratings correspond to stronger posterior-anterior connectivity, whereas lower ratings correspond to stronger ventral-dorsal connectivity (Connectivity-Direction × likelihood, β [standardized] = .28, p = .02). Yet, this is not a strong test of the reviewer’s hypothesis, and different exploratory analyses of response time yield null results (p > .05). We suspect that this is due to the effect being too subtle, so we have insufficient statistical power. A comparable analysis was not feasible for Study 1B, as its design does not provide an analogous behavioral measure of trialby-trial prediction success.

(R3.3) A priori Hypothesis for EEG Frequency Analysis.

It's unclear how to interpret the finding that fMRI fluctuations in the defined modules correlate with frontal Delta/Theta power, specifically in the 3-6 Hz range. However, in the EEG literature, this frequency band is most commonly associated with low arousal, drowsiness, and mind wandering in resting, awake adults, not uniquely with prediction error processing. An a priori hypothesis is lacking here: what specific frequency band would we expect to track spontaneous PE signals at rest, and why? Without this, it is difficult to separate a PE-based interpretation from more general arousal or vigilance fluctuations.

This point gets to the heart of the challenge with reverse inference in resting-state fMRI. We agree that an interpretation based on general arousal or drowsiness is a potential alternative that must be considered. However, what makes a simple arousal interpretation challenging is the highly specific nature of our fMRI-EEG association. As shown in our confirmatory analyses (Supplemental Materials 6), the correlation with 3-6 Hz power was found exclusively with the absolute difference between our two PE-related network states (|PA – VD|)—a measure of fluctuation amplitude. We found no significant relationship with the signed difference (a bias toward one state) or the sum (the overall level of connectivity). This specificity presents a puzzle for a simple drowsiness account; it seems less plausible that drowsiness would manifest specifically as the intensity of fluctuation between two complex cognitive networks, rather than as a more straightforward change in overall connectivity. While we cannot definitively rule out contributions from arousal, the specificity of our finding provides stronger evidence for a structured cognitive process, like PE, than for a general, undifferentiated state.

We updated the Discussion to make the argument above and also to remind readers that alternative explanations, such as ones based on drowsiness, are possible (p. 24):

“We specifically interpret the fMRI-EEG correlation as reflecting fluctuation speed because we correlated EEG oscillatory power with the fluctuation amplitude computed from fMRI data. Simply correlating EEG power with the average connectivity or the signed difference between posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity yields null results (Supplemental Materials 6), suggesting that this is a very particular association, and viewing it as capturing fluctuation amplitude provides a parsimonious explanation. Yet, this correlation may be interpreted in other ways. For example, resting-state Theta is also a signature of drowsiness,[2] which may correlate with PE processing, but perhaps should be understood as some other mechanism.”

(R3.4) Significance Assessment

The significance of the correlation above and all other correlation analyses should be assessed through a permutation test rather than a single parametric t-test against zero. There are a few reasons: a) EEG and fMRI time series are autocorrelated, violating the independence assumption of parametric tests;

Standard t-tests can underestimate the true null distribution's variance, because EEG-fMRI correlations often involve shared slow drifts or noise sources, which can yield spurious correlations and inflating false positives unless tested against an appropriate null.

Building a null distribution that preserves the slow drifts, for example, would help us understand how likely it is for the two time series to be correlated when the slow drifts are still present, and how much better the current correlation is, compared to this more conservative null. You can perform this by phase randomizing one of the two time courses N times (e.g., N=1000), which maintains the autocorrelation structure while breaking any true co-occurrence in patterns between the two time series, and compute a non-parametric p-value. I suggest using this approach in all correlation analyses between two time series.

This is an important statistical point to clarify, and the suggested analysis is valuable. The reviewer is correct that the raw fMRI and EEG time series are autocorrelated. However, because our statistical approach is a twolevel analysis, we reasoned that non-independence at the correlation-level would not invalidate the higher-level t-test. The t-test’s assumption of independence applies to the individual participants' coefficients, which are independent across participants. Thus, we believe that our initial approach is broadly appropriate, and its simplicity allows it to be easily communicated.

Nonetheless, the permutation-testing procedure that the Reviewer describes seems like an important analysis to test, given that permutation-testing is the gold standard for evaluating statistical significance, and it could guarantee that our above logic is correct. We thus computed the analysis as the reviewer described. For each participant, we phase-randomized the fMRI fluctuation amplitude time series. Specifically, we randomized the Fourier phases of the |PA–VD| series (within run), while retaining the original amplitude spectrum; inverse transforms yielded real surrogates with the same power spectrum. This was done for each participant once per permutation. Each participant’s phase-randomized data was submitted to the analysis of each oscillatory power band as originally, generating one mean correlation for each band. This was done 1,000 times.

Across the five bands, we find that the grand mean correlation is near zero (M<sub>r</sub> = .0006) and the 97.5<sup>th</sup> percentile critical value of the null distribution is r = ~.025; this 97.5<sup>th</sup> percentile corresponds to the upper end of a 95% confidence interval for a band’s correlation; the threshold minimally differs across bands (.024 < rs < .026). Our original correlation coefficients for Delta (M<sub>r</sub> = .042) and Theta (M<sub>r</sub> = .041), which our conclusions focused on, remained significant (p ≤ .002); we can perform family-wise error-rate correction by taking the highest correlation across any band for a given permutation, and the Delta and Theta effects remain significant (p<sub>FWE</sub>corrected ≤ .003); previously Reviewer comment R1.4c requested that we employ family-wise error correction.

These correlations were previously reported in Table 1, and we updated the caption to note what effects remain significant when evaluated using permutation-testing and with family-wise error correction (p. 19):

“The effects for Delta, Theta, Beta, and Gamma remain significant if significance testing is instead performed using permutation-testing and with family-wise error rate correction (p<sub>corrected</sub> < .05).”

We updated the Methods to describe the permutation-testing analysis (p. 43):

“To confirm the significance of our fMRI-EEG correlations with a non-parametric approach, we performed a group-level permutation-test. For each of 1,000 permutations, we phase-randomized the fMRI fluctuation amplitude time series. Specifically, we randomized the Fourier phases of the |PA–VD| series (within run), while retaining the original amplitude spectrum; inverse transforms yielded real surrogates with the same power spectrum. This procedure breaks the true temporal relationship between the fMRI and EEG data while preserving its structure. We then re-computed the mean Spearman correlation for each frequency band using this phase-randomized data. We evaluated significance using a family-wise error correction approach that accounts for us analyzing five oscillatory power bands. We thus create a null distribution composed of the maximum correlation value observed across all frequency bands from each permutation. Our observed correlations were then tested for significance against this distribution of maximums.”

(R3.5) Analysis choices

If I'm understanding correctly, the algorithm used to identify modules does so by assigning nodes to communities, but it does not itself restrict what edges can be formed from these modules. This makes me wonder whether the decision to focus only on connections between adjacent modules, rather than considering the full connectivity, was an analytic choice by the authors. If so, could you clarify the rationale? In particular, what justifies assuming that the gradient of PE states should be captured by edges formed only between nearby modules (as shown in Figure 2E and Figure 4), rather than by the full connectivity matrix? If this restriction is instead a by-product of the algorithm, please explain why this outcome is appropriate for detecting a global signature of PE states in both task and rest.

We discuss this matter in our response to comment R2.(4).

When assessing the correspondence across task-fMRI and rs-fMRI in section 2.2.2, why was the pattern during task calculated from selecting a pair of bilateral ROIs (resulting in a group of eight ROIs), and the resting state pattern calculated from posterior-anterior/ventral-dorsal fluctuation modules? Doesn't it make more sense to align the two measures? For example, calculating task effects on these same modules during task and rest?

We thank the reviewer for this question, as it highlights a point in our methods that we could have explained more clearly. The reviewer is correct that the two measures must be aligned, and we can confirm that they were indeed perfectly matched.

For the analysis in Section 2.2.2, both the task and resting-state measures were calculated on the exact same anatomical substrate for each comparison. The analysis iteratively selected a symmetrical subset of eight ROIs from our larger four quadrants. For each of these 3,432 iterations, we computed the task-fMRI PE effect (the Connectivity Direction × PE interaction) and the resting-state fluctuation amplitude (E[|PA – VD|]) using the identical set of eight ROIs. The goal of this analysis was precisely to test if the fine-grained anatomical pattern of these effects correlated within an individual across the task and rest states. We will revise the text in Section 2.2.2 to make this direct alignment of the two measures more explicit.

Recommendations for authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for authors):

(R1.3) Several prior studies have described co-activation or connectivity "templates" that spontaneously alternate during rest and task states, and are linked to behavioral variability. While they are interpreted differently in terms of cognitive function (e.g., in terms of sustained attention: Monica Rosenberg; alertness: Catie Chang), the relationship between these previously reported templates and those identified in the current study warrants discussion. Are the current templates spatially compatible with prior findings while offering new functional interpretations beyond those already proposed in the literature? Or do they represent spatially novel patterns?

Thank you for this suggestion. Broadly, we do not mean to propose spatially novel patterns but rather focus on how these are repurposed for PE processing. In the Discussion, we link our identified connectivity states to established networks (e.g., the FPCN). We updated this paragraph to mention that these patterns are largely not spatially novel (p. 20):

“The connectivity patterns put forth are, for the most part, not spatially novel and instead overlap heavily with prior functional and anatomical findings.”

Regarding the specific networks covered in the prior work by Rosenberg and Chang that the reviewer seems to be referring to, [7,8] this research has emphasized networks anchored heavily in sensorimotor, subcortical– cerebellar, and medial frontal circuits, and so mostly do not overlap with the connectivity effects we put forth.

(R1.4) Additional points:

(R1.4a) I do not think that the logic for taking the absolute difference of fMRI connectivity is convincing. What happens if the sign of the difference is maintained ?

Thank you for pointing out this area that requires clarification. Our analysis targets the amplitude of the fluctuation between brain states, not the direction. We define high fluctuation amplitude as moments when the brain is strongly in either the PA state (PA > VD) or the VD state (VD > PA). The absolute difference |PA – VD| correctly quantifies this intensity, whereas a signed difference would conflate these two distinct high-amplitude moments. Our simulation study (Supplemental Materials, Section 5) provides the theoretical validation for this logic, showing how this absolute difference measure in slow fMRI data can track the amplitude of a fast underlying neural oscillator.

When the analysis is tested in terms of the signed difference, as suggested by the Reviewer, the association between the fMRI data and EEG power is insignificant for each power band (ps<sub>uncorrected</sub> ≥ .47). We updated Supplemental Materials 6 to include these results. Previously, this section included the fluctuation amplitude (fMRI) × EEG power results while controlling for: (i) the signed difference between posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity, (ii) the sum of posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity, and (iii) the absolute value of the sum of posterior-anterior and ventral-dorsal connectivity. For completeness, we also now report the correlation between each EEG power band and each of those other three measures (SM, p. 9)

“We additionally tested the relationship between each of those three measures and the five EEG oscillation bands. Across the 15 tests, there were no associations (ps<sub>uncorrected</sub> ≥ .04); one uncorrected p-value was at p = .044, although this was expected given that there were 15 tests. Thus, the association between EEG oscillations and the fMRI measure is specific to the absolute difference (i.e., amplitude) measure.”

(R1.4b) Reasoning of focus on frontal and theta band is weak, and described as "typical" (line 359) based on a single study.

Sorry about this. There is a rich literature on the link between frontal theta and prediction error,[3,9–11] and we updated the Introduction to include more references to this work (p. 18): “The analysis was first done using power averaged across frontal electrodes, as these are the typical focus of PE research on oscillations.[3,9–11]”

We have also updated the Methods to cite more studies that motivate our electrode choice (p. 41): “The analyses first targeted five midline frontal electrodes (F3, F1, Fz, F2, F4; BioSemi64 layout), given that this frontal row is typically the focus of executive-function PE research on oscillations.[9–11]”

(R1.4c) No correction appears to have been applied for the association between EEG power and fMRI connectivity. Given that 100 frequency bins were collapsed into 5 canonical bands, a correction for 5 comparisons seems appropriate. Notably, the strongest effects in the delta and theta bands (particularly at fronto-central electrodes) may still survive correction, but this should be explicitly tested and reported.

Thanks for this suggestion. We updated the Table 1 caption to mention what results survive family-wise error rate correction – as the reviewer suggests, the Delta/Theta effects would survive Bonferroni correction for five tests, although per a later comment suggesting that we evaluate statistical significance with a permutationtesting approach (comment R3.4), we instead report family-wise error correction based on that. The revised caption is as follows (p. 19):

“The effects for Delta, Theta, Beta, and Gamma remain significant if significance testing is instead performed using permutation-testing and with family-wise error rate correction (p<sub>corrected</sub> < .05).”

(R1.4d) Line 135. Not sure I understand what you mean by "moods". What is the overall point here?

The overall argument is that the fluctuations occur rapidly rather than slowly. By slow “moods” we refer to how a participant could enter a high anxiety state of >10 seconds, linked to high PE fluctuations, and then shift into a low anxiety state, linked to low PE fluctuations. We argue that this is not occurring. Regardless, we recognize that referring to lengths of time as short as 10 seconds or so is not a typical use of the word “mood” and is potentially ambiguous, so we have omitted this statement, which was originally on page 6: “Identifying subsecond fluctuations would broaden the relevance of the present results, as they rule out that the PE states derive from various moods.”

(R1.4e) Line 100. "Few prior PE studies have targeted PE, contrasting the hundreds that have targeted BOLD". I don't understand this sentence. It's presumably about connectivity vs activity?

Yes, sorry about this typo. The reviewer is correct, and that sentence was meant to mention connectivity. We corrected (p. 5): “Few prior PE studies have targeted connectivity, contrasting the hundreds that have targeted BOLD.”

(R1.4f) Line 373: "0-0.5Hz" in the caption is probably "0-50Hz".

Yes, this was another typo, thank you. We have corrected it (p. 19): “… every 0.5 Hz interval from 0-50 Hz.”

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for authors):

(R2.6) (Page 3) When referring to the "limited" hypothesis of local PE, please clarify in what sense is it limited. That statement is unclear.

Thank you for pointing out this text, which we now see is ambiguous. We originally use "limited" to refer to the hypothesis's constrained scope – namely, that PE is relevant to various low-level operations (e.g., sensory processing or rewards) but the minimization of PE does not guide more abstract cognitive processes. We edited this part of the Introduction to be clearer (p. 3)

“It is generally agreed that the brain uses PE mechanisms at neuronal or regional levels,[15,16] and this idea has been useful in various low-level functional domains, including early vision [15] and dopaminergic reward processing.[17] Some theorists have further argued that PE propagates through perceptual pathways and can elicit downstream cognitive processes to minimize PE.”

(R2.7) (Page 5) "Few prior PE have targeted PE"... this statement appears contradictory. Please clarify.

Sorry about this typo, which we have corrected (p. 5):

“Few prior PE studies have targeted connectivity, contrasting the hundreds that have targeted BOLD.”

(R2.8) What happened to the data of the medium PE condition in Study 1A?

The medium PE condition data were not excluded. We modeled the effect of prediction error on connectivity using a linear regression across the three conditions, coding them as a continuous variable (Low = -1, Medium = 0, High = +1). This approach allowed us to identify brain connections that showed a linear increase or decrease in strength as a function of increasing PE. This linear contrast is a more specific and powerful way to isolate PErelated effects than a High vs. Low contrast. We updated the Results slightly to make this clearer (p. 8-9):

“In the fMRI data, we compared the three PE conditions’ beta-series functional connectivity, aiming to identify network-level signatures of PE processing, from low to high. […] For the modularity analysis, we first defined a connectome matrix of beta values, wherein each edge’s value was the slope of a regression predicting that edge’s strength from PE (coded as Low = -1, Medium = 0, High = +1; Figure 2A).”

(R2.9) (Page 15) The point about how the dots in 6H follow those in 6J better than those in 6I is a little subjective - can the authors provide an objective measure?

Thank you for pointing out this issue. The visual comparison using Figure 6 was not meant as a formal analysis but rather to provide intuition. However, as the reviewer describes, this is difficult to convey. Our formal analysis is provided in Supplemental Materials 5, where we report correlation coefficients between a very large number of simulated fMRI data points and EEG data points corresponding to different frequencies. We updated this part of the Results to convey this (p. 16-17):

“Notice how the dots in Figure 6H follow the dots in Figure 6J (3 Hz) better than the dots in Figure 6I (0.5 Hz) or Figure 6K (10 Hz); this visual comparison is intended for illustrative purposes only, and quantitative analyses are provided in Supplemental Materials 5.”

References

(1) Zalesky, A., Fornito, A. & Bullmore, E. T. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage 53, 1197–1207 (2010)

(2) Strijkstra, A. M., Beersma, D. G., Drayer, B., Halbesma, N. & Daan, S. Subjective sleepiness correlates negatively with global alpha (8–12 Hz) and positively with central frontal theta (4–8 Hz) frequencies in the human resting awake electroencephalogram. Neuroscience letters 340, 17–20 (2003).

(3) Cavanagh, J. F. & Frank, M. J. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends in cognitive sciences 18, 414–421 (2014).

(4) Grech, R. et al. Review on solving the inverse problem in EEG source analysis. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation 5, 25 (2008)

(5) Palva, J. M. et al. Ghost interactions in MEG/EEG source space: A note of caution on inter-areal coupling measures. Neuroimage 173, 632–643 (2018).

(6) Koles, Z. J. Trends in EEG source localization. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology 106, 127–137 (1998).

(7) Rosenberg, M. D. et al. A neuromarker of sustained attention from whole-brain functional connectivity. Nature neuroscience 19, 165–171 (2016).

(8) Goodale, S. E. et al. fMRI-based detection of alertness predicts behavioral response variability. elife 10, e62376 (2021).

(9) Cavanagh, J. F. Cortical delta activity reflects reward prediction error and related behavioral adjustments, but at different times. NeuroImage 110, 205–216 (2015)

(10) Hoy, C. W., Steiner, S. C. & Knight, R. T. Single-trial modeling separates multiple overlapping prediction errors during reward processing in human EEG. Communications Biology 4, 910 (2021).

(11) Neo, P. S.-H., Shadli, S. M., McNaughton, N. & Sellbom, M. Midfrontal theta reactivity to conflict and error are linked to externalizing and internalizing respectively. Personality neuroscience 7, e8 (2024).

(12) Friston, K. J. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature reviews neuroscience 11, 127–138 (2010)

(13) Feldman, H. & Friston, K. J. Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in human neuroscience 4, 215 (2010).

(14) Friston, K. J. et al. Active inference and epistemic value. Cognitive neuroscience 6, 187–214 (2015).

(15) Rao, R. P. & Ballard, D. H. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extraclassical receptive-field effects. Nature neuroscience 2, 79–87 (1999)

(16) Walsh, K. S., McGovern, D. P., Clark, A. & O’Connell, R. G. Evaluating the neurophysiological evidence for predictive processing as a model of perception. Annals of the new York Academy of Sciences 1464, 242– 268 (2020)

(17) Niv, Y. & Schoenbaum, G. Dialogues on prediction errors. Trends in cognitive sciences 12, 265–272 (2008).

(18) Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300 (1995).