https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/climate/patagonia-climate-philanthropy-chouinard.html

- Sep 2022

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

- Jul 2022

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

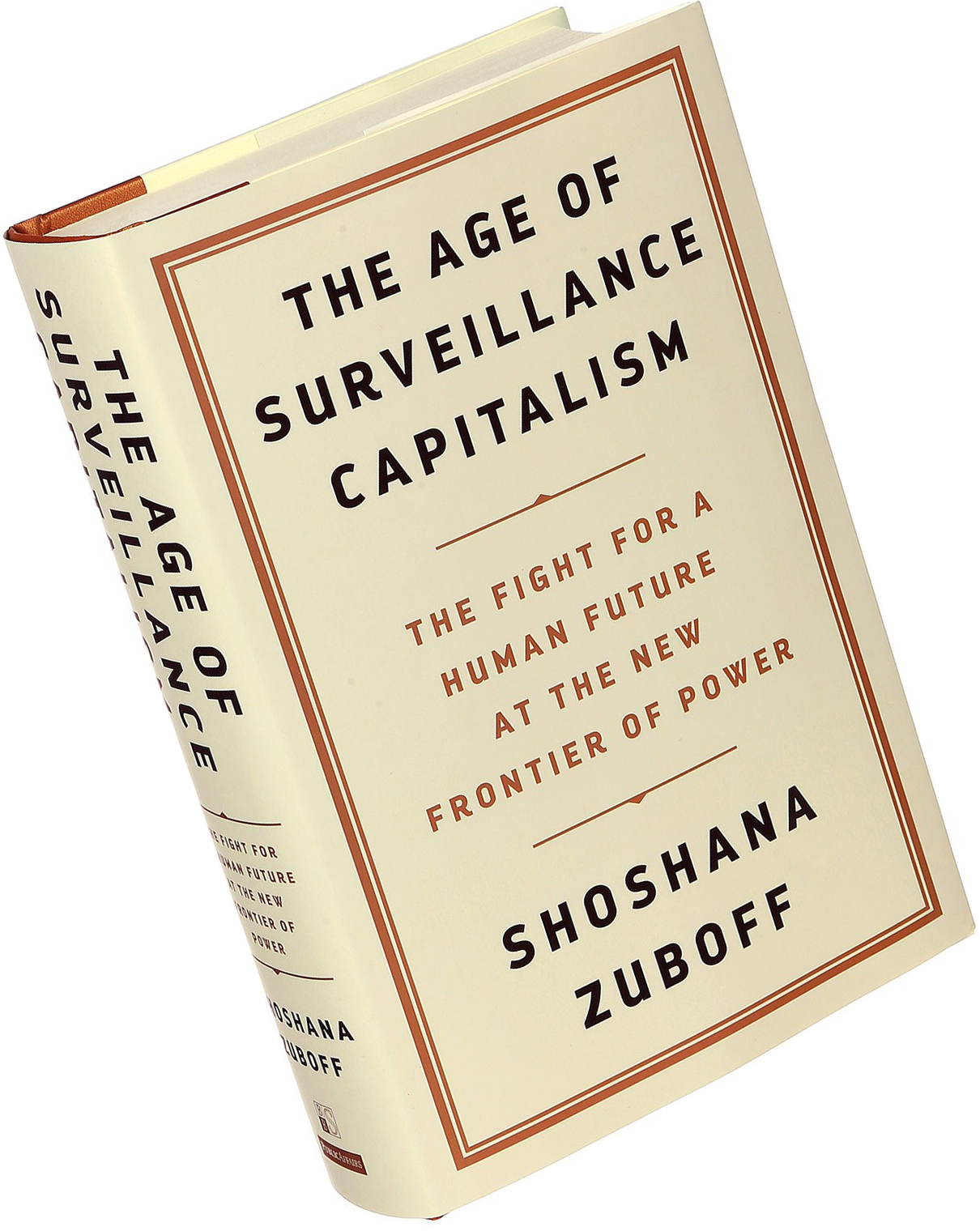

When we talk about “the algorithm,” we might be conflating recommender systems with online surveillance, monopolization, and the digital platforms’ takeover of all of our leisure time—in other words, with the entire extractive technology industry of the twenty-first century.

The algorithm’s role in surveillance capitalism

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Sounds like his philosophy fit may have fit in with the broader prosperity gospel space, Napoleon Hill, Billy Graham, Norman Vincent Peale, et al. Potentially worth looking into. Also related to the self-help movements and the New Thought philosophies.

fascinating that he wrote a book Copywriting and Direct Marketing. This may also tie him into the theses of Kevin Phillips' American Theocracy?

Link to: https://hyp.is/E4I_qgvCEe2rQO9iXvaTgA/www.goodreads.com/author/show/257221.Robert_Collier

Tags

- Napoleon Hill

- Robert Collier

- capitalism

- psychology

- Rhonda Byrne

- The Secret

- Collier's Weekly

- positive thinking

- self-help

- Billy Graham

- American Theocracy

- prosperity gospel

- metaphysics

- abundance

- Kevin Phillips

- copywriting

- Norman Vincent Peale

- religion

- visualization

- direct marketing

- desire

- Peter Fenelon Collier

- faith

- bookmark

Annotators

URL

-

-

ariadne.space ariadne.space

-

reply to: https://ariadne.space/2022/07/01/a-silo-can-never-provide-digital-autonomy-to-its-users/

Matt Ridley indicates in The Rational Optimist that markets for goods and services "work so well that it is hard to design them so they fail to deliver efficiency and innovation" while assets markets are nearly doomed to failure and require close and careful regulation.

If we view the social media landscape from this perspective, an IndieWeb world in which people are purchasing services like easy import/export of their data; the ability to move their domain name and URL permalinks from one web host to another; and CMS (content management system) services/platforms/functionalities, represents the successful market mode for our personal data and online identities. Here competition for these sorts of services will not only improve the landscape, but generally increased competition will tend to drive the costs to consumers down. The internet landscape is developed and sophisticated enough and broadly based on shared standards that this mode of service market should easily be able to not only thrive, but innovate.

At the other end of the spectrum, if our data are viewed as assets in an asset market between Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, et al., it is easy to see that the market has already failed so miserably that one cannot even easily move ones' assets from one silo to another. Social media services don't compete to export or import data because the goal is to trap you and your data and attention there, otherwise they lose. The market corporate social media is really operating in is one for eyeballs and attention to sell advertising, so one will notice a very health, thriving, and innovating market for advertisers. Social media users will easily notice that there is absolutely no regulation in the service portion of the space at all. This only allows the system to continue failing to provide improved or even innovative service to people on their "service". The only real competition in the corporate silo social media space is for eyeballs and participation because the people and their attention are the real product.

As a result, new players whose goal is to improve the health of the social media space, like the recent entrant Cohost, are far better off creating a standards based service that allows users to register their own domain names and provide a content management service that has easy import and export of their data. This will play into the services market mode which improves outcomes for people. Aligning in any other competition mode that silos off these functions will force them into competition with the existing corporate social services and we already know where those roads lead.

Those looking for ethical and healthy models of this sort of social media service might look at Manton Reece's micro.blog platform which provides a wide variety of these sorts of data services including data export and taking your domain name with you. If you're unhappy with his service, then it's relatively easy to export your data and move it to another host using WordPress or some other CMS. On the flip side, if you're unhappy with your host and CMS, then it's also easy to move over to micro.blog and continue along just as you had before. Best of all, micro.blog is offering lots of the newest and most innovative web standards including webmention notificatons which enable website-to-website conversations, micropub, and even portions of microsub not to mention some great customer service.

I like to analogize the internet and social media to competition in the telecom/cellular phone space In America, you have a phone number (domain name) and can then have your choice of service provider (hosting), and a choice of telephone (CMS). Somehow instead of adopting a social media common carrier model, we have trapped ourselves inside of a model that doesn't provide the users any sort of real service or options. It's easy to imagine what it would be like to need your own AT&T account to talk to family on AT&T and a separate T-Mobile account to talk to your friends on T-Mobile because that's exactly what you're doing with social media despite the fact that you're all still using the same internet. Part of the draw was that services like Facebook appeared to be "free" and it's only years later that we're seeing the all too real costs emerge.

This sort of competition and service provision also goes down to subsidiary layers of the ecosystem. Take for example the idea of writing interface and text editing. There are (paid) services like iA Writer, Ulysses, and Typora which people use to compose their writing. Many people use these specifically for writing blog posts. Companies can charge for these products because of their beauty, simplicity, and excellent user interfaces. Some of them either do or could support the micropub and IndieAuth web standards which allow their users the ability to log into their websites and directly post their saved content from the editor directly to their website. Sure there are also a dozen or so other free micropub clients that also allow this, but why not have and allow competition for beauty and ease of use? Let's say you like WordPress enough, but aren't a fan of the Gutenberg editor. Should you need to change to Drupal or some unfamiliar static site generator to exchange a better composing experience for a dramatically different and unfamiliar back end experience? No, you could simply change your editor client and continue on without missing a beat. Of course the opposite also applies—WordPress could split out Gutenberg as a standalone (possibly paid) micropub client and users could then easily use it to post to Drupal, micro.blog, or other CMSs that support the micropub spec, and many already do.

Social media should be a service to and for people all the way down to its core. The more companies there are that provide these sorts of services means more competition which will also tend to lure people away from silos where they're trapped for lack of options. Further, if your friends are on services that interoperate and can cross communicate with standards like Webmention from site to site, you no longer need to be on Facebook because "that's where your friends and family all are."

I have no doubt that we can all get to a healthier place online, but it's going to take companies and startups like Cohost to make better choices in how they frame their business models. Co-ops and non-profits can help here too. I can easily see a co-op adding webmention to their Mastodon site to allow users to see and moderate their own interactions instead of forcing local or global timelines on their constituencies. Perhaps Garon didn't think Webmention was a fit for Mastodon, but this doesn't mean that others couldn't support it. I personally think that Darius Kazemi's Hometown fork of Mastodon which allows "local only" posting a fabulous little innovation while still allowing interaction with a wider readership, including me who reads him in a microsub enabled social reader. Perhaps someone forks Mastodon to use as a social feed reader, but builds in micropub so that instead of posting the reply to a Mastodon account, it's posted to one's IndieWeb capable website which sends a webmention notification to the original post? Opening up competition this way makes lots of new avenues for every day social tools.

Continuing the same old siloing of our data and online connections is not the way forward. We'll see who stands by their ethics and morals by serving people's interests and not the advertising industry.

-

- Jun 2022

-

Local file Local file

-

We’ve been conditioned to view information through aconsumerist lens: that more is better, without limit.

-

-

hybridpedagogy.org hybridpedagogy.org

-

Get a copy of Critical Digital Pedagogy: A Collection

I can't help but wonder at the direct link here to Amazon with an affiliate link. I won't fault them completely for it, but for a site that is so critical of the ills of educational technology, and care for their students and community, the exposure to surveillance capitalism expressed here seems to go beyond their own pale. I would have expected more care here.

Surely there are other platforms that this volume is available from?

-

-

www.nbcnews.com www.nbcnews.com

-

“Data is the new oil,” she said.

Oft repeated phrase and one I wouldn't have expected in this article.

-

But the copyright on the materials still gives the organization control over how the information is used, which is what some tribal leaders find objectionable.

Oral cultures treat information dramatically different than literate cultures, and particularly Western literate cultures within capitalism-based economies.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Private tech companies have greater power to influence, censor and control the lives of ordinary people than any government on earth

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- May 2022

-

Local file Local file

-

Ken Pomeranz’s study, published in 2000, on the “greatdivergence” between Europe and China in the eighteenth and nine-teenth centuries,1 prob ably the most important and influential bookon the history of the world-economy (économie-monde) since the pub-lication of Fernand Braudel’s Civilisation matérielle, économie etcapitalisme in 1979 and the works of Immanuel Wallerstein on “world-systems analysis.”2 For Pomeranz, the development of Western in-dustrial capitalism is closely linked to systems of the internationaldivision of labor, the frenetic exploitation of natural resources, andthe European powers’ military and colonial domination over the restof the planet. Subsequent studies have largely confirmed that conclu-sion, whether through the research of Prasannan Parthasarathi orthat of Sven Beckert and the recent movement around the “new his-tory of capitalism.”3

-

-

seirdy.one seirdy.one

-

The ad lists various data that WhatsApp doesn’t collect or share. Allaying data collection concerns by listing data not collected is misleading. WhatsApp doesn’t collect hair samples or retinal scans either; not collecting that information doesn’t mean it respects privacy because it doesn’t change the information WhatsApp does collect.

An important logical point. Listing what they don't keep isn't as good as saying what they actually do with one's data.

-

-

www.propublica.org www.propublica.org

-

Under the radar, a new class of dangerous debt — climate-distressed mortgage loans — might already be threatening the financial system. Lending data analyzed by Keenan and his co-author, Jacob Bradt, for a study published in the journal Climatic Change in June shows that small banks are liberally making loans on environmentally threatened homes, but then quickly passing them along to federal mortgage backers. At the same time, they have all but stopped lending money for the higher-end properties worth too much for the government to accept, suggesting that the banks are knowingly passing climate liabilities along to taxpayers as stranded assets.

We need better ways of making valuations and assessing risk so that these sorts of dangerous debt can't be passed along.

These sorts of sales should have long term baggage clauses built into them to prevent government "suckers". If they fail within x number of years, the original owners and their investors are held liable for them.

-

-

doctorow.medium.com doctorow.medium.com

-

The next time someone tells you “If you’re not paying for the product, you’re the product,” remember this. These farmers weren’t getting free, ad-supported tractors. Deere charges six figures for a tractor. But the farmers were still the product. The thing that determines whether you’re the product isn’t whether you’re paying for the product: it’s whether market power and regulatory forbearance allow the company to get away with selling you.

Nuanced "If you're not paying for the product, you're the product"

Is your demographic and/or activity data being sold? Then you are still the product even if you are paying for something.

I worry about things like Google Workspace sometimes. Am I paying enough for the product to cover the cost of supplying the product to me, or is Google having to raise additional revenue to cover the cost of serving me? Is Google raising additional revenue even though they don't have to in order to cover my cost?

-

-

www.eff.org www.eff.org

-

We've had three things happen simultaneously: we've moved from an open web where people start lots of small projects to one where it really feels like if you're not on a Facebook or a YouTube, you're not going to reach a billion users, and at that point, why is it worth doing this? Second, we've developed a financial model of surveillance capitalism, where the default model for all of these tools is we're going to collect as much information as we can about you and monetize your attention. Then we've developed a model for financing these, which is venture capital, where we basically say it is your job to grow as quickly as possible, to get to the point where you have a near monopoly on a space and you can charge monopoly rents. Get rid of two aspects of that equation and things are quite different.

How We Got Here: Concentration of Reach, Surveillance Capitalism, and Venture Capital

These three things combined drove the internet's trajectory. Without these three components, we wouldn't have seen the concentration of private social spaces and the problems that came with them.

-

- Apr 2022

-

barackobama.medium.com barackobama.medium.com

-

these companies need to have some other North Star other than just making money and increasing market share

Will regulation be able to change the North Star?

-

-

pioneerworks.org pioneerworks.org

-

As a general rule, if your call is to dismantle institutions without a plan for what is supposed to take their place, you can safely assume the default setting is “the market will take care of it.”

-

- Mar 2022

-

every.to every.to

-

You also need to design a compensation structure that pays writers what they’re worth.

A writer's collective trying to gather writers using the bait that they've managed to crack the problem of "paying writers what they're worth" seems to be a lot of hype.

This seems to put the already extant fear into a writer's mind that they're not being paid enough. Doesn't the broader economics of a capitalistic system already solve this issue? Where are the inequalities? What about paying the website designers and developers? What about the advertising and other marketing people?

-

We’re building a knowledge base, so if one writer collects information for an article, their research is made available to the other writers in the collective.

How does one equitably and logically build a communally shared knowledge base for a for-profit space?

How might a communal zettelkasten work? A solid index for creating links between pieces is incredibly important here, but who does this work? How is it valued?

-

-

www.cs.umd.edu www.cs.umd.edu

-

Posting a new algorithm, poem, or video on the web makes it a vailable, but unless appropriate recipients notice it, the originator has little chance to influence them.

An early statement of the problem of distribution which has been widely solved by many social media algorithmic feeds. Sadly pushing ideas to people interested in them (or not) doesn't seem to have improved humanity. Perhaps too much of the problem space with respect to the idea of "influence" has been devoted to marketing and commerce or to fringe misinformation spaces? How might we create more value to the "middle" of the populace while minimizing misinformation and polarization?

-

Refinement is a social process: New ideas are conceived of by individuals, and then they are refined through reviews from knowledgeable peers and mentors.

Refinement is a social process. Sadly it can also be accelerated, often negatively, by unintended socio-economic forces.

The dominance and ills created by surveillance capitalism within social media is one such result driven by capitalism.

-

- Feb 2022

-

seths.blog seths.blog

-

The second reason might support positive change. The existence of tokens and decentralization means that it’s possible to build resilient open source communities where early contributors and supporters benefit handsomely over time. No one owns these communities, and we can hope that these communities will work hard to serve themselves and their users, not the capital markets or other short-term players.

Capitalism's subject is Capital, not the bourgeoisie or an owner class. "Open source communities" are still corporations.

-

And that’s the first reason that the blockchain matters—because there’s a chance that it might lead to more open, resilient, market-focused networks and databases. It’s only a chance, though, because all the hype around the tokens sometimes makes it seem more likely that financial operators will simply seek to manipulate unregulated markets for their own benefit.

There's no chance. Blockchains by principle benefit corporations in the long run.

-

Because the internet rewards people who own networks so handsomely, these organizations continue to gain in power. Google began by building a database on top of the open internet, and they’ve spent the last twenty years relentlessly making the internet less open so they can fortify the power of their databases and the attention they influence or control.

Openness by itself can't make a dent against corporations.

-

Now imagine a blockchain/token project in which contributors earned tokens as they built it and supported it. Over time, the decentralized project would go up in value. As the ecosystem and the market delivered more and more utility to more and more people, the users would need to buy tokens to use it. And the holders of tokens would receive either a dividend or have the ability to sell their tokens if they chose. Early speculators would attract more attention, and people with more skill than capital could invest by contributing early and often. As the project reached a steady state, the stakeholders would shift, from innovators and speculators to people who treat their daily contributions as a job without a boss. Innovators could build on top of this network without permission, creating more and more variations and choice using the same underlying database.

This is a nightmare, and it would possibly be capitalism's final victory.

-

-

kotaku.com kotaku.com

-

One source described the Q&A as an ultimately unsuccessful attempt at extracting some kind of accountability from Stadia management.

There is no accountability to people inside corporations, only to results. Which is working as intended, companies are meant to make money by serving customers, not employees.

The simple "truth" here is that these Stadia games likely wouldn't have been successful without a lot of additional investments.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Hmm...this page doesn’t exist. Try searching for something else.

Apparently Persuall was embarrassed about their pro-surveillance capitalism stance and perhaps not so much for its lack of kindness and care for the basic humanity of students.

Sad that they haven't explained or apologized for their misstep.

https://web.archive.org/web/20220222022208/https://twitter.com/perusall/status/1495945680002719751

Additional context: https://twitter.com/search?q=(%40perusall)%20until%3A2022-02-23%20since%3A2022-02-21&src=typed_query

-

Original tweet thread archived: https://web.archive.org/web/20220222025045/https://twitter.com/perusall/status/1495945680002719751

-

-

perusall.com perusall.comPerusall1

-

Stay at the forefront of educational innovation

What about a standard of care for students?

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>Bragging about students not knowing how the surveillance technology works is unethical.<br><br>Students using accessibility software or open educational resources shouldn't be punished for accidentally avoiding surveillance. pic.twitter.com/Uv7fiAm0a3

— Ian Linkletter (@Linkletter) February 22, 2022

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>#annotation https://t.co/wVemEk2yao

— Remi Kalir (@remikalir) February 23, 2022

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Comaroff and Comaroff (2000) - Millennial Capitalism: First Thoughts on a Second Coming - https://is.gd/yWCl8i - urn:x-pdf:a8e24543f52dc4c4cf554706560c993f

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

That's because of bargaining power. Government programs, like Medicare and Medicaid, can ask for a lower price from health service providers because they have the numbers: the hospital has to comply or else risk losing the business of millions of Americans.

Big public sector drives health-services prices down.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

davidharvey.org davidharvey.org

-

at the very outset a sense of how the elements or “moments” (as Marx prefers to call them) of the capitalist economic system, such as production, labour, wages, profit, consumption, exchange, realization and distribution

At the onset, if possible - - it would be preferable to have a clear understanding of what and how Marx would define the following three terms: 1. What is capital? 2. What is capitalism? 3. What is a capitalist economic system?

The list of eight (8) elements or "moments" combined with the phrase "totality of what capital is all about". appears to be somewhat confusing. Did you mean to say what "capitalism is all about"? Or, does "capital" consists of a list of "things" as well as (at least one) process?

And, are these 8 items all part of one single process - - called "capital" which is then transformed into different elements or "moments" as it circulates? Or, are there 8 separate interrelated processes?

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

In , power is the governing principle as rooted in of private ownership. Private ownership is wholly and only an act of institutionalized , and institutionalized exclusion is a matter of organized power

capitalism as system of organized power

-

-

chomsky.info chomsky.info

-

Back in 1981, a State Department insider boasted that we would "turn Nicaragua into the Albania of Central America"-that is, poor, isolated and politically radical-so that the Sandinista dream of creating a new, more exemplary political model for Latin America would be in ruins.

Cruelty of the imperialistic US administrator is telling of what we can achieve without toxic capitlalism.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

doctorow.medium.com doctorow.medium.com

-

Preventing cheating during remote test-taking:https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/17/proctorio-v-linkletter/#proctorioSpying on work-from-home employees:https://pluralistic.net/2020/07/01/bossware/#bosswareSpying on students and their families:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robbins_v._Lower_Merion_School_DistrictRepossessing Teslas:https://tiremeetsroad.com/2021/03/18/tesla-allegedly-remotely-unlocks-model-3-owners-car-uses-smart-summon-to-help-repo-agent/Disabling cars after a missed payment:https://edition.cnn.com/2009/LIVING/wayoflife/04/17/aa.bills.shut.engine.down/index.htmlForcing you to buy official printer ink:https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/11/ink-stained-wretches-battle-soul-digital-freedom-taking-place-inside-your-printerSpying on people who lease laptops:https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2012/09/ftc-halts-computer-spyingBricking gear the manufacturer doesn’t want to support anymore:https://memex.craphound.com/2016/04/05/google-reaches-into-customers-homes-and-bricks-their-gadgets/

This is some really troubling developments for all first world people, especially educators

-

- Jan 2022

-

notesfromasmallpress.substack.com notesfromasmallpress.substack.com

-

If booksellers like to blame publishers for books not being available, publishers like to blame printers for being backed up. Who do printers blame? The paper mill, of course.

The problem with capitalism is that in times of fecundity things can seem to magically work so incredibly well because so much of the system is hidden, yet when problems arise so much becomes much more obvious.

Unseen during fecundity is the amount of waste and damage done to our environments and places we live. Unseen are the interconnections and the reliances we make on our environment and each other.

There is certainly a longer essay hiding in this idea.

-

-

canvas.ucsc.edu canvas.ucsc.eduFiles1

-

The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin

- Benjamin is part of the Frankfurt School at Institute of Social Studies in Germany.

- They are trying to examine the failure of Marxist revolutionary social change.

- The idea is that ideology disseminated through mass media are making it very difficult for Marx's prognotication are making it very difficult for social change to occur.

- 19th century modernity: mass transportation, factory work, dissemination of capitalism, movement to cities and experience of urban life

These convergent endeavors made predictable a situation which Paul Valéry pointed up in this sentence: “Just as water, gas, and electricity are brought into our houses from far off to satisfy our needs in response to a minimal effort, so we shall be supplied with visual or auditory images, which will appear and disappear at a simple movement of the hand, hardly more than a sign.” (op. cit., p. 226) Around 1900 technical reproduction had reached a standard that not only permitted it to reproduce all transmitted works of art and thus to cause the most profound change in their impact upon the public; it also had captured a place of its own among the artistic processes. For the study of this standard nothing is more revealing than the nature of the repercussions that these two different manifestations—the reproduction of works of art and the art of the film—have had on art in its traditional form.

Q: Why does it matter that film minimizes the aura?

At the time, art reacted with the doctrine of l’art pour l’art, that is, with a theology of art. This gave rise to what might be called a negative theology in the form of the idea of ‘pure’ art, which not only denied any social function of art but also any categorizing by subject matter. (In poetry, Mallarmé was the first to take this position.) An analysis of art in the age of mechanical reproduction must do justice to these relationships, for they lead us to an all-important insight: for the first time in world history, mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual. To an ever greater degree the work of art reproduced becomes the work of art designed for reproducibility.7 From a photographic negative, for example, one can make any number of prints; to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense. But the instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice—politics.<br> Ritual: pre-modern timesPolitics: Despite the political painting the art piece will be associated with the aura of original piece of art.

- Film is not auratic because in film: 1) spaces and times are constructed 2) actors performance is stitched together 3) actors do not share space with spectators 4) multiple points of view 5) appeals to a MASS AUDIENCE and a COLLECTIVE AUDIENCE 6) reveals new aspects of the thing reproduced (time alpse, slow motion).

How do institutions put the aura back into film?

In photography, exhibition value begins to displace cult value all along the line. But cult value does not give way without resistance. It retires into an ultimate retrenchment: the human countenance.

The superstar is a way to put the aura back into film

The film responds to the shriveling of the aura with an artificial build-up of the “personality” outside the studio. The cult of the movie star, fostered by the money of the film industry, preserves not the unique aura of the person but the “spell of the personality,” the phony spell of a commodity. So long as the movie-makers’ capital sets the fashion, as a rule no other revolutionary merit can be accredited to today’s film than the promotion of a revolutionary criticism of traditional concepts of art. We do not deny that in some cases today’s films can also promote revolutionary criticism of social conditions, even of the distribution of property. However, our present study is no more specifically concerned with this than is the film production of Western Europe.

*Marx says capitalism produces the seeds of its demise. We can think of that as a guiding principle in which capitalism produces the neorosis that leads Chaplins character into a destructive set of behaviors that stops the Fordist capitalist production in a factory.

Feelings of belongoing and togetherness and being overhwemed by a mass you want to be a part of , but for Benjamin this is a trynanny where people feel they are in control but they are not really in control. Thus communism replies by politicizing art. Art for art's sake is harmful when put in the service of a facist regime. Art for political progress.

The growing proletarianization of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two aspects of the same process. Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves.21 The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property. The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life. The violation of the masses, whom Fascism, with its Führer cult, forces to their knees, has its counterpart in the violation of an apparatus which is pressed into the production of ritual values.

Film is not merely a translation of an in-person thetaer performance. Rather film is performing for future audiences and for the director and for cinematrography. This supports the idea that film is a collabroative creation that brings an object into the world.

One film can be playing multiple times around the world and so this can be distributed on mass scale.

Film is not merely a recording of reality. Film reproduced new aspects of the things reproduced through slow motion and it brings to light entirely new aspects of matter but discloses quite aspects within them. If Benjamin merely interested in the epistemological possibility of the film to expand our limited perceptual appartus, yes but think about how this reinforces his claim that film moves us away from the aura,...that if we can see unknown aspects by recording it then we can't rely on film to reproduce an original we have to keep in mind that the image is qualitatively distinct from our perceptual access to the thing. So film is not merely a copy of the thing that it records.

Benjamin flips things and says that maybe film isn't art the way we see an art and this will get us away from the trappings.

What is Benjamin's definition of art which he is defining with the aura, the transcendence of individual of ritual.

- substructure or base: factors that produce commodities and economic relations that result from these concrete aspects

- superstructure: culture, law, media that for a Marxist thinker emerges in the way that the economic structure functions; the more media/education/political cosumption that you do the less you are going to understand the conditions of your exploitation and the more you are going to think change is possible.

- What role does cinema play in the move from cult and aura to mechanical reproduction? See snapshots.

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

In a recent paper, Pierre Azoulay and co-authors concluded that Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s long-term grants to high-potential scientists made those scientists 96 percent more likely to produce breakthrough work. If this finding is borne out, it suggests that present funding mechanisms are likely to be far from optimal, in part because they do not focus enough on research autonomy and risk taking.

Risk taking and the potential return are key pieces of progress.

Most of our research funding apparatus isn't set up with a capitalistic structure. Would that be good or bad for accelerating progress?

-

-

learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com

-

Europeans were constantly squabbling for advantage; societies ofthe Northeast Woodlands, by contrast, guaranteed one another themeans to an autonomous life – or at least ensured no man or womanwas subordinated to any other. Insofar as we can speak ofcommunism, it existed not in opposition to but in support of individualfreedom.

Why can't we have some of the driving force of capitalism while ensuring that no person is subordinated to another while still supporting individual freedoms?

Where did Western culture go wrong in getting stuck in a death lock with capitalism?

-

-

www.noemamag.com www.noemamag.com

-

Raw capitalism mimics the logic of cancer within our body politic.

Folks who have been reading David Wengrow and David Graeber's The Dawn of Everything are sure to appreciate the sentiment here which pulls in the ideas of biology and evolution to expand on their account and makes it a much more big history sort of thesis.

-

- Dec 2021

-

pluralistic.net pluralistic.net

-

DoS a federal agency, then charge for access

Capitalism run amok. Force a public good or commons into a corner so it's unusable, then charge for access to it.

-

-

web.archive.org web.archive.org

-

Yet the existence of an independent and goodwill-based web is endangered : threatened by the never-ending technology race which makes the websites more difficult and expensive to set up, by the overwhelming commercial advertising pressure, and soon by dissymetric networks, Network Computers, proprietary networks, broadcasting, all aiming at the transformation of the citizen into a basic consumer.

An early notice of the rise of consumerism on the web and potentially prefiguring the rise of surveillance capitalism.

-

-

www.independent.co.uk www.independent.co.uk

-

Dogs’ innate sense of fairness being eroded by humans, study suggests https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/dogs-wolves-unfairness-acceptance-human-owners-pets-behaviour-research-vienna-a7779076.html

While thinking about inequality in reading The Dawn of Everything, I started thinking about inequality and issues in other animal settings.

Why am I not totally surprised to find that animals' innate sense of fairness could be eroded by humans?

I wonder if this effect might be seen across all cultures, or only Western cultures with capitalist economies? Could we look at dogs in Australian indigenous cultures and find the same results?

-

-

-

We live under governments that are too captured by the near-term priorities of capitalism to seriously address the threat of climate change

Inability of politics to go beyond sort-term objectives

-

-

www.efsyn.gr www.efsyn.gr

-

Παρόμοιες είναι οι ιστορίες δεκάδων ακόμη δισεκατομμυριούχων που συναντάμε στη λίστα των 100 πλουσιότερων ανθρώπων του κόσμου. Ακόμη και αν οι γονείς τους δεν διέθεταν αμύθητες περιουσίες, σχεδόν όλοι μεγάλωσαν σε ένα περιβάλλον το οποίο τους διέκρινε από τη συντριπτική πλειονότητα των κατοίκων του πλανήτη. Ο Μαρκ Ζούκερμπεργκ της Facebook (126 δισ. δολάρια), παραδείγματος χάριν, είχε τη δυνατότητα να σπουδάσει στην ιδιωτική ακαδημία Phillips Exeter (ετήσιο κόστος διδάκτρων 57.000 δολάρια), ενώ από τα 11 του χρόνια είχε τον προσωπικό του καθηγητή που του μάθαινε προγραμματισμό (γεγονός που προφανώς του έδωσε τον τίτλο του «παιδιού θαύματος» των υπολογιστών). Η μητέρα του Σεργκέι Μπριν (121.9 δισ. δολάρια) ήταν ερευνήτρια στη NASA, ενώ ο πατέρας του Γουάρεν Μπάφετ (105,2 δισ. δολάρια) ήταν μεγαλο-επενδυτής και γερουσιαστής επί σειρά ετών.

Όσο για την κοινωνική κινητικότητα του Καπιταλισμου, πλεον ουτε να παντρυετείς τον πλούτο δεν γινεται, μονο να τον κληρονομήσεις.

-

-

apenwarr.ca apenwarr.ca

-

Writing all this down, you know what? I'm kind of mad about it too. Not so mad that I'll go chasing obviously-ill-fated scurrilous rainbow financial instruments. But there's something here that needs solving. If I'm not solving it, or part of it, or at least trying, then I'm... wasting my time. Who cares about money? This is a systemic train wreck, well underway. We have, in Western society, managed to simultaneously botch the dreams of democracy, capitalism, social coherence, and techno-utopianism, all at once. It's embarrassing actually. I am embarrassed. You should be embarrassed.

I love you so much Avery Pennarun. It's so cathartic to hear such plain & simple truth telling. Your blog post is full of so many wonderful plainly said things. This is such a non-controversial, clear statement of so much of the tension & conflict we're in, so well reduced.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Nov 2021

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

They say that hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, and I can only imagine the conversation between Eve and Skywoman: “Sister, you got the short end of the stick . . .”

It's a bit funny and ironic to think that the communal/peaceful Skywoman would use such a Western-centric phrase like "short end of the stick", which as I understand it has an economic underpinning of a receipt by which the debtor and the lender used marked sticks that were broken apart with one somewhat shorter than the other. When put back together the marks on the stick matched each other, but the debtor got the shorter end. (Reference: Behavioral Economics When Psychology and Economics Collide by Scott A. Huettel; what was his source?)

Compare with etymologies expanded upon here:

The Long Story of The Short End of the Stick by Charles Clay Doyle. American Speech, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 96-101 (6 pages), Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/455954

Which doesn't include the economic reference at all.

-

-

www.forbes.com www.forbes.com

-

a desire, a search and active discovery reach to enhance our collective experiences

A builders collective?

We have realized that we want more in our lives than to be the unwitting pawns in a game of global domination, genocide, slavery, and oppression called capitalism.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Striketober is the labor strike wave in October 2021 by workers in the United States in the context of strikes during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the month, more than 100,000 workers in the United States either participated in or prepared for strikes in one of the largest increases of organized labor in the twenty-first century.

Perhaps people have finally had a chance to read Debt by David Graeber or Temp by Louis Hyman or Winners Take All by Anand Giridharadas.

This is the great disillusionment in capitalism that Forbes will not talk about. What have we been building this whole time? Colonization, slavery, and genocide on steroids enabled by big tech and big business? Maybe people just want their self-respect back.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

The climate catastrophe we're facing is the result of three issues, three processes.

- The tragedy of the commons, the free-rider problem

- Coordination (money is there)

- Capitalist beast eating up everything to survive.

The first 2 are solvable - for the 3rd we need to reconsider [[property rights]].

-

s now exalting in all of those subsidies and those bailouts and using that to even consolidate themselves even more than they did in 1933 and 1971.

These are the big stops of capitalism during 20th century and beyond:

- 1933: Roosvelt nationalized the gold from the private banks

- 19171: Nixon dismantled [[Bretton Woods]]

- 2007-2020: Lehman Brothers & #Covid19 crisis consolidated international capital

-

-

-

so we're going to ask first who thinks capitalism albeit with tweaks and reforms is still the best economic system we've got so if you think that give us a wave

It seems as if 80% raised their hands, believing that Capitalism if the best economic system, and very few raised hands, later, believing that a new economic system is needed. A bit reasonable, since it would cost thousands to enter the room, no?

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.project-syndicate.org www.project-syndicate.org

-

The entire capitalist system is premised on the privatization of gains and the socialization of losses – not in any nefarious fashion, but with the blessing of the law.

-

-

www.robinrendle.com www.robinrendle.com

-

I think of the Kindle and what enormous potential that browser had to change our relationship with the internet, to push it towards a web that you read (instead of one that tries so very hard to read you).

I love the phrase "a web that your read instead of one that tries so very hard to read you."

-

- Oct 2021

-

bilge.world bilge.world

-

Over the course of this super link-laden journey, we’d consider the alarmingly hypocritical possibility that it’s been overlooked by mainstream conversations only because it has so long operated in the precise manner we claim is so hopelessly absent from its neighbors in its deliberate, principled, and innovative journey towards a transparent, progressive vision.

In retrospect, the dynamic I'm addressing here is bascially My Whole Shit. That is - one of (if not the) primary forces that have compelled The Psalms.

-

-

threadreaderapp.com threadreaderapp.com

-

-

"Consumer" is LITERALLY replacing "citizen" as an identity.

-

-

networkcultures.org networkcultures.org

-

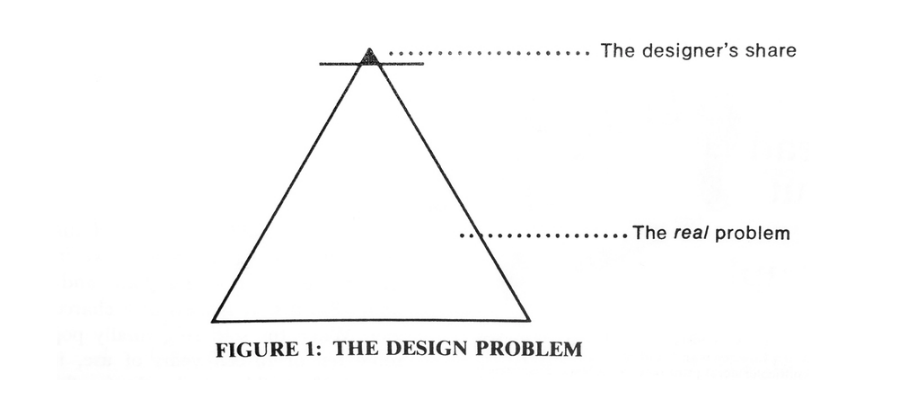

Victor Papanek’s Design Problem, 1975.

The Design Problem

Three diagrams will explain the lack of social engagement in design. If (in Figure 1) we equate the triangle with a design problem, we readily see that industry and its designers are concerned only with the tiny top portion, without addressing themselves to real needs.

(Design for the Real World, 2019. Page 57.)

The other two figures merely change the caption for the figure.

- Figure 1: The Design Problem

- Figure 2: A Country

- Figure 3: The World

-

-

sandyandnora.com sandyandnora.com

-

At the beginning of this episode, Sandy Hudson tells Nora Loreto about a podcast on NPR, Invisibilia.

The episodes that I listened to were about an anti-news news website in Stockton, California. How news has shifted and changed.

The Invisibilia episode is entitled, The Chaos Machine: An Endless Hole.

I ended up following this rabbit hole all the way to The View from Somewhere podcast episode featuring a discussion of Hallin’s spheres. Truly fascinating!

-

-

www.canadaland.com www.canadaland.com

-

Stories about the dirty business of Canadian mining.

Canadaland: Commons

Introducing our new season… Mining

Stories about the dirty business of Canadian mining.

Mining is a dirty business, but it is what Canada does best. Three-quarters of the world’s mining companies are best right here in the Great White North.

In our new season, Commons: Mining, we’ll be digging deep into the practices and the history of the extractive industry. From the gold rushes that shaped the country to the cover-ups and the outright frauds at home and abroad.

Canada was built on extracting what lay under the land, no matter the damage it did or who it ended up hurting.

The first episode of Commons: Mining comes out on October 13th.

Canada is fake

Canada is not an accident or a work in progress or a thought experiment. I mean that Canada is a scam — a pyramid scheme, a ruse, a heist. Canada is a front. And it’s a front for a massive network of resource extraction companies, oil barons, and mining magnates.

Extraction Empire

Globally, more than 75% of prospecting and mining companies on the planet are based in Canada. Seemingly impossible to conceive, the scale of these statistics naturally extends the logic of Canada’s historical legacy as state, nation, and now, as global resource empire.

Canada’s Indian Reserve System served, officially, as a strategy of Indigenous apartheid (preceding South African apartheid) and unofficially, as a policy of Indigenous genocide (preceding the Nazi concentration camps of World War II).

Theft on a grand scale

It’s really been about theft on a grand scale. Look at how the United Kingdom became rich, or England and then Britain as it was, at the time. It was through bleeding India dry, we bled $45 trillion out of India. We taxed the subcontinent until there was virtually nothing left, then used a small amount of that tax money to buy its goods. So we were buying goods with their own money. And then we used the phenomenal profits — 100% profits — from that enterprise to finance the capture of other nations, and the colonization of those nations and the citizens, the railways and the other things we built in order to drain wealth out of them.

— George Monbiot

-

-

bauhouse.medium.com bauhouse.medium.com

-

It’s really been about theft on a grand scale. Look at how the United Kingdom became rich, or England and then Britain as it was, at the time. It was through bleeding India dry, we bled $45 trillion out of India. We taxed the subcontinent until there was virtually nothing left, then used a small amount of that tax money to buy its goods. So we were buying goods with their own money. And then we used the phenomenal profits — 100% profits — from that enterprise to finance the capture of other nations, and the colonization of those nations and the citizens, the railways and the other things we built in order to drain wealth out of them.

Theft on a Grand Scale

-

CapitalismTheft on a grand scale

-

-

www.monbiot.com www.monbiot.com

-

The young people taking to the streets are right: their future is being stolen. The economy is an environmental pyramid scheme, dumping its liabilities on the young and the unborn. Its current growth depends on intergenerational theft.

Theft on a grand scale

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

As Morgan says, masters, “initially at least, perceived slaves in much the sameway they had always perceived servants . . . shiftless, irresponsible, unfaithful,ungrateful, dishonest. . . .”

Interestingly, this is still all-too-often how business owners, entrepreneurs, and corporations view their own workers.

-

-

bauhouse.medium.com bauhouse.medium.comMonopoly1

-

monopoly over public discourse

This is the water we swim in.

-

- Sep 2021

-

pluralistic.net pluralistic.net

-

Piketty, of course, is the bestselling French economist whose 2013 Capital in the 21st Century was an unlikely, 700+ page viral hit, describing with rare lucidity the macroeconomics that drive capitalism towards cruel and destabilizing inequality https://memex.craphound.com/2014/06/24/thomas-pikettys-capital-in-the-21st-century/

Great summary of Piketty's book.

-

-

tracydurnell.com tracydurnell.com

-

You might be looking for a gift for a friend, doing research for a project, trying to learn other perspectives — they filter all data through the lens of capitalism and how they can sell you more things. That’s no replacement for human connection, or expertise a person has that could help you leap to things you didn’t know to look for.

-

-

tracydurnell.com tracydurnell.com

-

Are women generally more interested in other social causes besides online surveillance and the negative cultural impacts of social media companies?

Most of the advanced researchers I seen on these topics are almost all women: Safiya Umoja Noble, Meredith Broussard, Ruha Benjamin, Cathy O'Neil, Shoshana Zuboff, Joan Donovan, danah boyd,Tressie McMillan Cottom, to name but a few.

The tougher part is that they are all fighting against problems created primarily by privileged, cis-gender, white men.

-

-

www.lboro.ac.uk www.lboro.ac.uk

-

there has been a spectacular rise in luxury consumption, with the consumption patterns of the global elite acting as a marker for those further down the income scale. Robert Frank (2000) describes the process as 'luxury fever', as consumption expectations are ratcheted up all the way down the income scale. The global elite are pushing up people's expectations and assumptions. In the US, for example, the average size of house has doubled, in square feet terms, in the past thirty years. In part it is a function of the positional nature of consumption. We consume in order to position ourselves relative to other people. Not only do the global elite raise the upper limit, everyone is thus forced to spend more just to keep up, but they also become the perceived benchmark, Juliet Schor's work, for example, shows that people are no longer keeping up with the people next door, but the people they see on television and magazines (Schor, 1998). In order to keep up with these raised consumption standards people are working harder and longer as well as taking out more debt. The increase in luxury consumption has raised consumption expectations further down the income scale, which in order to be funded has involved increased workloads and increased indebtedness. It is not so much keeping up with the Jones but 'keeping up with the Gates'.

The elites point the way for those in even the lowest income brackets to follow. This crosses cultures as well. Capitalism trumps colonialism as former colonized peoples reserve the right to taste the fruits of capitalism. Hence, hard work, ingenuity and leveraging opportunity to accumulate all the signs and symbols of wealth, joining the colonialist biased elites is seen as having arrived at success, even though it means contributing to the destruction of the planetary commons. The aspirations to wealth must be uniformly deprioritized in order to align our culture in the right direction that will rescue our species from the impact of following this misdirection for the past century.

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

Under these conditions, perhaps one of every three blacks transportedoverseas died, but the huge profits (often double the investment on one trip)made it worthwhile for the slave trader, and so the blacks were packed into theholds like fish

With the earlier death rate of two of every five dying on the death marches to the slave markets and one in every three dying on the ships, this means that 9/15 or a full 60% were dying before they even arrived in America.

This is certainly a disgusting indictment of capitalistic frenzy.

-

Africanslavery lacked two elements that made American slavery the most cruel formof slavery in history: the frenzy for limitless profit that comes from capitalisticagriculture; the reduction of the slave to less than human status by the use ofracial hatred, with that relentless clarity based on color, where white wasmaster, black was slave.

While we've generally moved beyond chattel slavery, I'm struck by the phrase frenzy for limitless profit that comes from capitalistic agriculture. Though we don't have slavery, is American culture all-too captured by the idea of frenzied capitalism to the tune that the average American (the 99%) is a serf in their own country? Are we still blinded by our need for (over-)consumption?

Are we recommitting the sins of the past perhaps in milder forms because of a blindness to an earlier original sin of capitalism?

Do we need to better vitiate against raw capitalism with more regulation to provide a healthier mixed economy?

-

The Virginians needed labor, to grow corn for subsistence, to grow tobaccofor export. They had just figured out how to grow tobacco, and in 1617 theysent off the first cargo to England. Finding that, like all pleasurable drugstainted with moral disapproval, it brought a high price, the planters, despitetheir high religious talk, were not going to ask questions about something soprofitable.

Told from this perspective and with the knowledge of the importance of the theory of First Effective Settlement, is it any wonder that America has grown up to be so heavily influenced by moral and mental depravity, over-influenced by capitalism and religion, ready to enslave others, and push vice and drugs? The founding Virginians are truly America in miniature.

Cross reference: Theory of First Effective Settlement

“Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settlers may have been.” “Thus, in terms of lasting impact, the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later.” — Wilbur Zelinsky, The Cultural Geography of the United States, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973, pp. 13–14.

-

-

sakai.duke.edu sakai.duke.edu

-

n the extraordinary Law Book of the Crowley Iron Works. Here, at the very birth of the large-scale unit in manufacturing industry, the old autocrat, Crowley, found it necessary to design an entire civil and penal code, running to more than Ioo,ooo words, to govern and regulate his refractory labour-force.

A historical precursor to the company-town. One wonders if this was used as a model by Hershey, Pullman, Levittown(s), etc.?

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Kevin Marks talks about the bridging of new people into one's in-group by Twitter's retweet functionality from a positive perspective.

He doesn't foresee the deleterious effects of algorithms for engagement doing just the opposite of increasing the volume of noise based on one's in-group hating and interacting with "bad" content in the other direction. Some of these effects may also be bad from a slow brainwashing perspective if not protected for.

-

-

www.propublica.org www.propublica.org

-

The Uncomfortable Truth is the Difficult and Unpopular Decisions are Now Unavoidable.

Topic is relevant across a span of global issues. Natural resources are Finite.....period! Timely decisions are critical to insure intelligent use of resources. DENIAL is the enemy and 800lb gorilla in the room. Neoliberisim and social dysfunction feed on any cognitive dissonance and poop it out as "crap". True believers of American Capitalism (yes there is a difference) have become "cult-like" and drink the fluid of the cult to the very end, human consequence is of no concern.

Point being: Reality is always elusive within a cult controlled (authoritative) mindset. Cult members are weak sheep, incapable of individual logic/reason. Authority can not be challenged. -- Denial, a human defense mechanism has been and is the common denominator in all personal and global conflict. Denial can be traced throughout modern history and rears its ugly head whenever the stakes are high.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

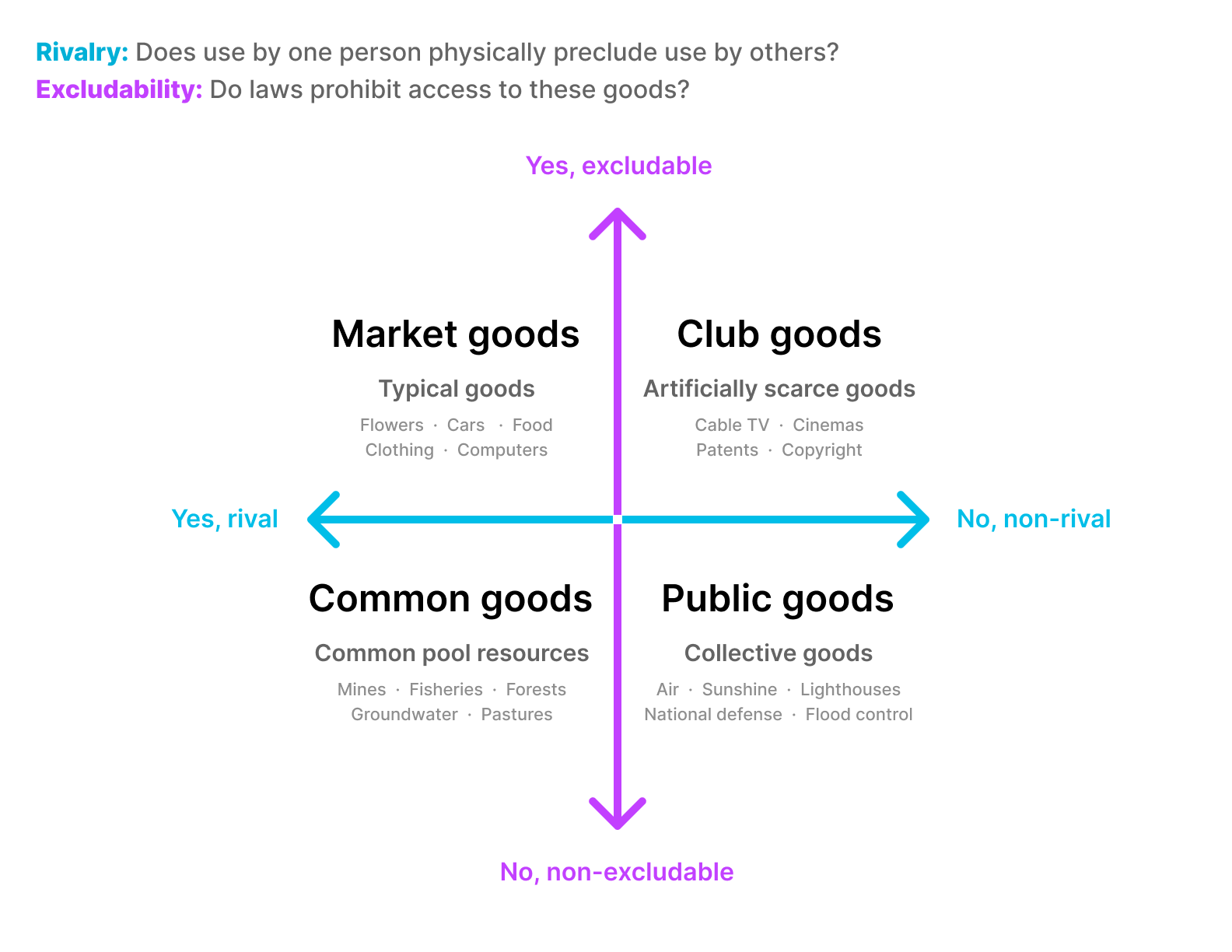

What happens to this graph when we overlay pure capitalism instead of a mixed economy? What if this spectrum was put on a different axis altogether? What does the current climate of the United states look like when graphed out on it. Which parts have diminished over the past 50 years with the decrease in regulation?

Some of these areas benefit heavily by government intervention and regulation.

We need the ability to better protect both common and public goods.

definitions:

- rivalry: does use by one person physically preclude use by others?

- excludability: do laws prohibit access to these goods?

-

- Aug 2021

-

algorithmsoflatecapitalism.tumblr.com algorithmsoflatecapitalism.tumblr.comZines1

-

Algorithms of Late-Capitalism’ zine.

-

-

thepressproject.gr thepressproject.gr

-

Η ευθύνη για την αντιμετώπιση της πανδημίας δεν ανήκει πρωτίστως στους ανεμβολίαστους του πρώτου κόσμου, αλλά στις νεοφιλελεύθερες πολιτικές των κυβερνήσεών τους και στην υποταγή στα εταιρικά συμφέροντα.

Οι ψεκες έχουν μικρή συμμετοχή στις μεταλλάξεις, λέει κ η Λαμπρινή Θωμά.

-

-

-

Building on platforms' stores of user-generated content, competing middleware services could offer feeds curated according to alternate ranking, labeling, or content-moderation rules.

Already I can see too many companies relying on artificial intelligence to sort and filter this material and it has the ability to cause even worse nth degree level problems.

Allowing the end user to easily control the content curation and filtering will be absolutely necessary, and even then, customer desire to do this will likely loose out to the automaticity of AI. Customer laziness will likely win the day on this, so the design around it must be robust.

-

- Jul 2021

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

In April 2000, Clinton hosted a celebration called the White House Conference on the New Economy. Earnest purpose mingled with self-congratulation; virtue and success high-fived—the distinctive atmosphere of Smart America. At one point Clinton informed the participants that Congress was about to pass a bill to establish permanent trade relations with China, which would make both countries more prosperous and China more free. “I believe the computer and the internet give us a chance to move more people out of poverty more quickly than at any time in all of human history,” he exulted.

This is a solid example of the sort of rose colored glasses too many had for technology in the early 2000s.

Was this instance just before the tech bubble collapsed too?

What was the state of surveillance capitalism at this point?

-

-

edwardsnowden.substack.com edwardsnowden.substack.com

-

-

If this past year-and-change has taught us anything, it's how interconnected we all are — a bat coughs and the world gets sick. Vaccines aside, our greatest weapon for defeating Covid-19 has been the mask, an accessory I'd formerly appreciated only a symbol: masks make secret, masks hide, masks cover, in protests as in pandemics. The social value of the mask has been made clear: they're not deceptive so much as protective, of ourselves and of others too. Masking is a mutual responsibility, a symbol of common identity founded in a common hope.

The idea of a bat coughing and infecting the world is a powerful one in relation to our interconnectedness.

I'm enamored of how he transitions this from the pandemic and masking for protection against virus to using masks as a symbol for protecting ourselves, our data, and our identity in a surveillance state.

-

The intimate linking of users' online personas with their offline legal identity was an iniquitous squandering of liberty and technology that has resulted in today's atmosphere of accountability for the citizen and impunity for the state. Gone were the days of self-reinvention, imagination, and flexibility, and a new era emerged — a new eternal era — where our pasts were held against us. Forever.

Even Heraclitus knew that one couldn't stand in the same river twice.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.comYouTube1

-

i feel for for tool builders that are serious about building useful software interoperability can actually be a huge 00:45:22 spoon uh to their success um it'll make easier to acquire users it will make it easier to help users embed your own tool in their workflows um you may be also losing some users but 00:45:34 that's okay i guess because it'll create sustainable pressure to you for you to focus on an audience well and build really really useful services for them and if you do that they also won't leave as easily

I agree. I think companies that allow their users to take their data and run when they want to just create trust. Gone are the days when users automatically thought companies had their best interests at heart, as compared with current-day surveillance capitalists.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

aeon.co aeon.co

-

It’s a familiar trick in the privatisation-happy US – like, say, underfunding public education and then criticising the institution for struggling.

This same thing is being seen in the U.S. Post Office now too. Underfund it into failure rather than provide a public good.

Capitalism definitely hasn't solved the issue, and certainly without government regulation. See also the last mile problem for internet service, telephone service, and cable service.

UPS and FedEx apparently rely on the USPS for last mile delivery in remote areas. (Source for this?)

The poor and the remote are inordinately effected in almost all these cases. What other things do these examples have in common? How can we compare and contrast the public service/government versions with the private capitalistic ones to make the issues more apparent. Which might be the better solution: capitalism with tight government regulation to ensure service at the low end or a government monopoly of the area? or something in between?

-

-

stop.zona-m.net stop.zona-m.net

-

Broad recycle of Tim Bray's article https://www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/201x/2018/01/15/Google-is-losing-its-memory with an example of the same effect for their site.

DuckDuckGo has a better index that doesn't prioritize for "right now" or currency.

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Forty years ago, Michel Foucault observed in a footnote that, curiously, historians had neglected the invention of the index card. The book was Discipline and Punish, which explores the relationship between knowledge and power. The index card was a turning point, Foucault believed, in the relationship between power and technology.

This piece definitely makes an interesting point about the use of index cards (a knowledge management tool) and power.

Things have only accelerated dramatically with the rise of computers and the creation of data lakes and the leverage of power over people by Facebook, Google, Amazon, et al.

-

-

ayjay.org ayjay.org

-

Against Canvas

I love that he uses this print of Pablo Picasso's Don Quixote to visually underline this post in which he must feel as if he's "tilting at windmills".

-

All humanities courses are second-class citizens in the ed-tech world.

And worse, typically humans are third-class citizens in the ed-tech world.

-

- Jun 2021

-

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>KevinMarks</span> in #indieweb 2021-06-25 (<time class='dt-published'>06/26/2021 01:52:39</time>)</cite></small>

IndieWeb + Welsh finally comes in handy! The Cwtch service Kevin Marks mentioned is the the Welsh word for "hug" or "cuddle" and cleverly has a heart shaped Celtic design for their logo. Kind of cute when you think about it. And speaking of opaque ids, if they're using a new protocol I hope they call it Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch....

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

If so many people who say they have committed their life to Christ live a life that is in many areas so antithetical to the ways of Christ, what are we to make of that?

Does Christianity still have a space in modern life if it can't be effective in the simplest ways?

Is it christianity+capitalism and conspicuous consumption that doesn't work?

What is causing this institutional failure?

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

The idea that our minds should operate as high-speed data-processing machines is not only built into the workings of the Internet, it is the network’s reigning business model as well. The faster we surf across the Web—the more links we click and pages we view—the more opportunities Google and other companies gain to collect information about us and to feed us advertisements. Most of the proprietors of the commercial Internet have a financial stake in collecting the crumbs of data we leave behind as we flit from link to link—the more crumbs, the better. The last thing these companies want is to encourage leisurely reading or slow, concentrated thought. It’s in their economic interest to drive us to distraction.

Here it is in July 2008, Nicholas Carr has essentially specified and created a small warning bell about the surveillance capitalism we've been experiencing for the past 13 years. He's also put a bright yellow highlight on the method by which they would do it.

What are other early surveillance capitalism warning sources from this period?

-

- May 2021

-

blogs.harvard.edu blogs.harvard.edu

-

Doc Searls blames the cookie for poisoning the web.

-

-

www.cnbc.com www.cnbc.com

-

“Finance is, like, done. Everybody’s bought everybody else with low-cost debt. Everybody’s maximised their margin. They’ve bought all their shares back . . . There’s nothing there. Every industry has about three players. Elizabeth Warren is right,” Ubben told the Financial Times.

Pretty amazing statement! Elizabeth Warren is right!

-

-

howtomeasureghosts.substack.com howtomeasureghosts.substack.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Kevin Marks</span> in "@alexstamos You gave a pithy quote about 'strangers' which downplayed the sustained attempts by the social silos to gather and document our lives in their dossiers and cash in on it. @matlock explains more here https://t.co/lo4dG4CuqV" / Twitter (<time class='dt-published'>05/18/2021 19:32:39</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.buzzfeednews.com www.buzzfeednews.com

-

“For one of the most heavily guarded individuals in the world, a publicly available Venmo account and friend list is a massive security hole. Even a small friend list is still enough to paint a pretty reliable picture of someone's habits, routines, and social circles,” Gebhart said.

Massive how? He's such a public figure that most of these connections are already widely reported in the media or easily guessable by an private invistigator. The bigger issue is the related data of transactions which might open them up for other abuses or potential leverage as in the other examples.

-

-

crookedtimber.org crookedtimber.org

-

To change incentives so that personal data is treated with appropriate care, we need criminal penalties for the Facebook executives who left vulnerable half a billion people’s personal data, unleashing a lifetime of phishing attacks, and who now point to an FTC deal indemnifying them from liability because our phone numbers and unchangeable dates of birth are “old” data.

We definitely need penalties and regulation to fix our problems.

-

I know tech policy pretty well, and this absolute dumpster fire of a policy area isn’t just a cool new place to build a blockchain-based commons, but a hard-right haven of male libertarians asset-stripping the social democratic state to build global monopolies that re-run nineteenth century colonialism, but bigger.

A well stated version of our current problem.

-

-

signal.org signal.org

-

This would be funnier if it weren't so painfully true.

-

- Apr 2021

-

www.techiechan.com www.techiechan.com

-

Σε μια οικονομία που το χρήμα τυπώνεται και προσφέρεται στους ημετέρους, το κίνητρο του κέρδους είναι ανύπαρκτο· ενώ το πραγματικό κίνητρο (όπως πάντα) είναι ο έλεγχος. Το χρήμα είναι το μέσο με το οποίο επιτυγχάνεται αυτός ο έλεγχος.

Δεν υπάρχει (πλέον) ανταγωνισμός, γινόμαστε σοβιετία, απλώς με μεγαλύτερες ανισότητες και κατανεμημένο πολίτμπιρο.

-

-

mignano.medium.com mignano.medium.com

-

The open RSS standard has provided immense value to the growth of the podcasting ecosystem over the past few decades.

Why do I get the sinking feeling that the remainder of this article will be maniacally saying, "and all of that ends today!"

-

We also believe that in order to democratize audio and achieve Spotify’s mission of enabling a million creators to live off of their art, we must work to enable greater choice for creators. This choice becomes increasingly important as audio becomes even easier to create and share.

Dear Anchor/Spotify, please remember that democratize DOES NOT equal surveillance capitalism. In fact, Facebook and others have shown that doing what you're probably currently planning for the podcasting space will most likely work against democracy.

-

Thus, the creative freedom of creators is limited.

And thus draconian methods for making the distribution unnecessarily complicated, siloed, surveillance capitalized, and over-monitized beyond all comprehension are beyond the reach of one or two for profit companies who want to own the entire market like monopolistic giants are similarly limited. (But let's just stick with the creators we're pretending to champion, shall we?)

-

-

-

Και όμως, θα αρκούσε μια πιο διεισδυτική ματιά στο «κίνημα των απαλλοτριώσεων» και των «περιφράξεων» της εποχής του, που μετέτρεπε την κοινόχρηστη γη σε ατομική ιδιοκτησία, για να αντιληφθεί ότι ο καταμερισμός εργασίας και η αγορά είναι αποτέλεσμα κοινωνικών και πολιτικών διεργασιών.

Δεν είχε καταλάβει ο Ανταμ Σμιθ πως ο πλούτος φέρνει πλούτο, δηλαδή.

-

-

www.wired.com www.wired.com

-

So on a blindingly sunny day in October 2019, I met with Omar Seyal, who runs Pinterest’s core product. I said, in a polite way, that Pinterest had become the bane of my online existence.“We call this the miscarriage problem,” Seyal said, almost as soon as I sat down and cracked open my laptop. I may have flinched. Seyal’s role at Pinterest doesn’t encompass ads, but he attempted to explain why the internet kept showing me wedding content. “I view this as a version of the bias-of-the-majority problem. Most people who start wedding planning are buying expensive things, so there are a lot of expensive ad bids coming in for them. And most people who start wedding planning finish it,” he said. Similarly, most Pinterest users who use the app to search for nursery decor end up using the nursery. When you have a negative experience, you’re part of the minority, Seyal said.

What a gruesome name for an all-too-frequent internet problem: miscarriage problem

-

- Mar 2021

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

The scholars Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias have called it “data colonialism,” a term that reflects our inability to stop our data from being unwittingly extracted.

I've not run across data colonialism before.

-

-

www.opendemocracy.net www.opendemocracy.net

-

We will never be able to predict with any certainty how altering instrumental and socio-affective traits will ultimately affect the reflexively structured human personality as a whole. Today's tacit assumption that neuro-psychotropic interventions are reversible is leading individuals to experiment on themselves. Yet even if certain mental states are indeed reversible, the memory of them may not be. The barriers to neuro-enhancement actually fell some time ago, albeit in ways that for a long time went unnoticed. Jet-lag-free short breaks to Bali, working for global companies with a twenty-four hour information flow from headquarters in Tokyo, Brussels and San Francisco, exams and assessments, medical emergency services

The machinery of capital requires productivity and the psychopharmacology industry has stepped in to fulfill that requirements.

-

Unlike the latter, however, the neurosciences are extremely well funded by the state and even more so by private investment from the pharmaceutical industry.

More reasons to be wary. The incentive structure for the research is mostly about control. It's a little sinister. It's not about helping people on their own terms. It's mostly about helping people become "good" citizens and participants of the state apparatus.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

"So capitalism created social media. Literally social life, but mediated by ad sellers." https://briefs.video/videos/why-the-indieweb/

Definition of social media: social life, but mediated by capitalistic ad sellers online.

-

- Feb 2021

-

hyperallergic.com hyperallergic.com

-

There is only one way to “play” Twitter, and the only real gain is that “No one is learning anything, except to remain connected to the machine.”

Ik vraag me af of dat echt zo is. Twitter lijkt meer en meer de plek te worden om je eigen media op te bouwen en het eigen spel te spelen. Er zijn meerdere manieren om het spel te spelen. Toch?

-

The tech takeover corresponds with shrinking possibilities. This evolution has also seen the rise of a seeming aesthetic paradox. Minimalist design reigns now that the corporations have taken over the net. Long seen as anti-consumerist, Minimalism has now become a coded signal for luxury and control. The less control we have over our virtual spaces, the less time we spend considering our relationships with them.

Interessante laatste zin. Hoe minder we eigen controle hebben, zeggenschap, agency, hoe minder we ons bezighouden met de aard van de relatie. Die relatie kan verschillende vormen hebben.

-

-

onezero.medium.com onezero.medium.com

-

identity theft

Saw this while scrolling through quickly. Since I can't meta highlight another hypothesis annotation

identity theft

I hate this term. Banks use it to blame the victims for their failure to authenticate people properly. I wish we had another term. —via > mcr314 Aug 29, 2020 (Public) on "How to Destroy ‘Surveillance C…" (onezero.medium.com)

This is a fantastic observation and something that isn't often noticed. Victim blaming while simultaneously passing the buck is particularly harmful. Corporations should be held to a much higher standard of care. If corporations are treated as people in the legal system, then they should be held to the same standards.

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Cory Doctorow</span> in Pluralistic: 16 Feb 2021 – Pluralistic: Daily links (<time class='dt-published'>02/25/2021 12:20:24</time>)</cite></small>

It's interesting to note that there are already two other people who have used Hypothes and their page note functionality to tag this article as to read, one with

(to read)and another with(TODO-read).

-

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-